A Rare Exploration of the Obstacles on the Inner Path, as Revealed in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

By Eddie Stern

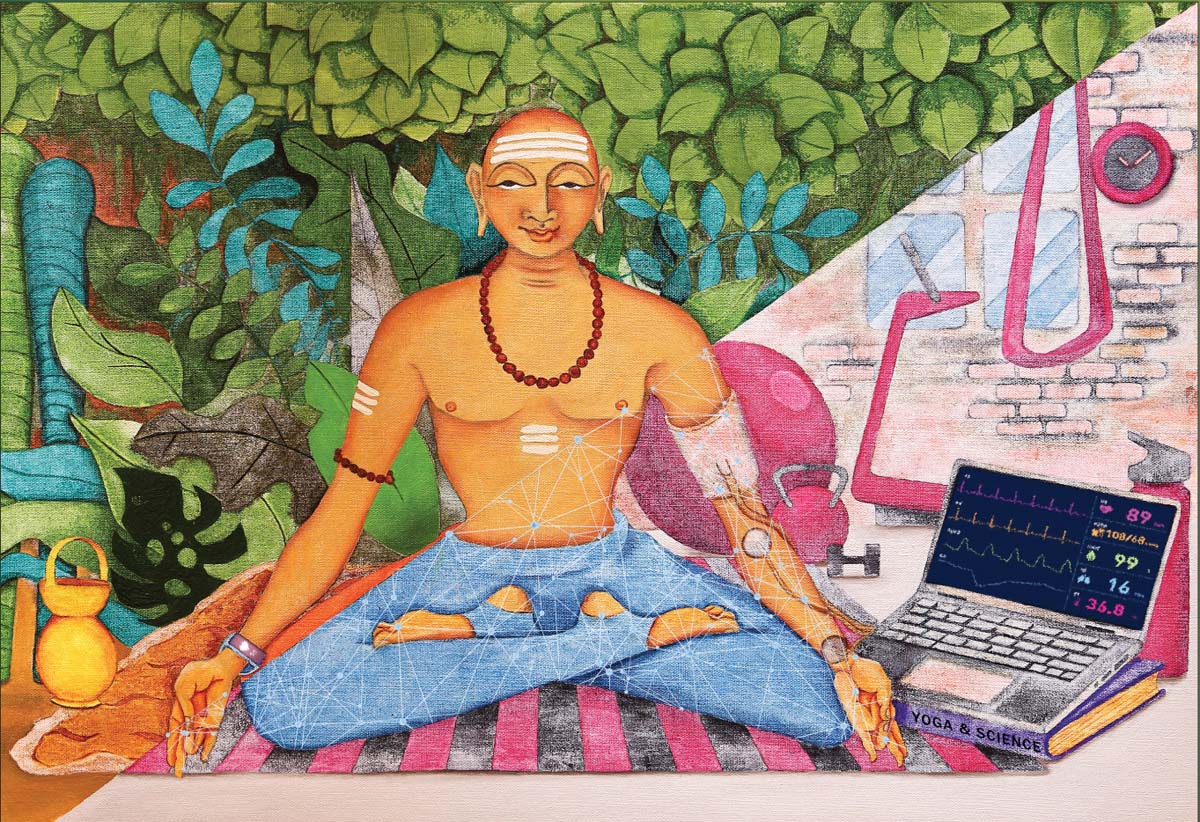

The practice of yoga and the science of yoga, or yogabhyasa and yogavidya, are two of the traditional ways that yoga is described. Yoga is a practice (abhyasa) and a science (vidya). While asanas and pranayama are immensely popular and currently the most visible expressions of the practice of yoga, the science of yoga has a deep and ancient history, though it has not enjoyed the same recent popularity on a public scale as postures have. There is a distinction that needs to be made between the Western definition of science and the Sanskrit word vidya, which means both science and knowledge. While both the Sanskritic and Western translations of science incorporate knowledge, understanding, investigation and quantification, the West regards science as examining observable phenomena that can be verified through measurement and data collection, while the Hindu and yogic sciences accept one’s inner experience as a valid source of data collection (pratyaksha). The inner experience is, in fact, the primary source of knowledge, while anything that is observed, heard or inferred is secondary (Yoga Sutra, 1.7). As well, the inner source of knowledge may be an immeasurable, something the West does not factor into science. It’s hard to measure something that, by definition, is immeasurable. I had heard from my teachers in India for many years that yoga is a process of internal revelation, the Self revealing itself in the conscious awareness of the seeker. Liberation, and even wisdom, are not something to be added to you from the outside, but revealed from the inside. So, to busy oneself collecting data and amassing information, while useful for sharpening the intellect, is not as useful for inner growth. This idea led me to focus on internal practices for the better part of two decades—that is until Western science came knocking on my door and I answered. A scientist named Dr. Marshall Hagins, having been referred to me by a student, wanted to know if I could create a yoga protocol for a study focused on treating hypertension. His hypothesis was that the practices of asanas and pranayama would have a down-regulating effect on hypertension through the actions on the vagus nerve. My interest was piqued.

Yoga Principles

Swami Kuvalyananda (1883–1966) was the first Indian to study yoga using Western scientific methodologies in an effort to find a meeting place of the two doctrines. Though both are of immense value as stand-alone disciplines, he felt they could help each other progress in an increasingly modern society. He knew that Western science was not necessary to prove that yoga worked—yoga had already been proven to work, as its practices had been perpetuated for several millennia in India already. But by using Western science to examine the efficacies of yoga, there could be discoveries of side benefits, and that could encourage those who might benefit from it to take up its practice, both in India and abroad. He famously said, “Persons that are equipped with an undying faith in spiritual culture and its attainment through yogic practices require no scientific interpretations of these for their progress. But those that take their stand upon reason would be satisfied with nothing short of a scientific explanation of yoga, if they are to be induced to take to it.” (Psycho-physiology, Spiritual and Physical Culture, etc., with their application to Therapeutics, Kuvalayananda S., Yoga Mimamsa 1:79-80, 1924.)

One could make the case that much of what we think of as scientific thought is making a supposition and then using research, experimentation, examination and more suppositions to eventually reach repeatable and dependable conclusions. Those conclusions often lead to more discoveries that expand a particular field of focus. The framework of yogavidya follows this same trajectory, while making up a dialogue of yoga that has been occurring now for thousands of years. Much of what is referenced in yoga teachings today is from the writings of Bhagavan Patanjali, the author of the Yoga Sutras (400ce), an unparalleled collection of aphorisms that define the essence of yoga. In the first few sutras, Patanjali makes it abundantly clear that yoga is a practice for quieting and eliminating the extraneous activities of the mind to lead us away from states of limited self-awareness. Yoga is the process of eliminating discursive thought so the mind can be directed towards one object of attention, and the process of thinning or removing the seed impressions from which our thoughts arise. These impressions are called samskaras—memories and subtle impressions in the subconscious mind. When these two processes—of focused awareness and removal of impressions—reach their pinnacle, our awareness shifts from identifying with thoughts and the myriad of subtleties of feelings, emotions, memories and shifting identities, and reverts to its original identity of ultimate awareness of the Self alone, abiding then in its original, pristine freedom. The methodology of achieving this is strategic and described as a step-by-step process. To follow that process is to engage in the endeavor of yogabhyasa which is based on the instructions, anushasanam, explained through the yogavidya.

Oddly, we see little of this deeper understanding in the field of yoga today. Asanas and pranayama are the most visible and popular practices in India and in the West. Nowadays when people say the word yoga you can almost assume that they are talking about yoga postures and equating the two. On the one hand, we could say that simply doing asanas is not really practicing yoga at all—or perhaps just partially. Sri Krishnamacharya agreed with this when he stated that the practice of yoga begins when we realize we are suffering, and take active steps to not only remove suffering, but to understand and recognize its source. Anyone can do asanas and pranayamas, he continued, but those practices only become yoga when they are done with the express purpose to remove suffering.

Kriya Yoga

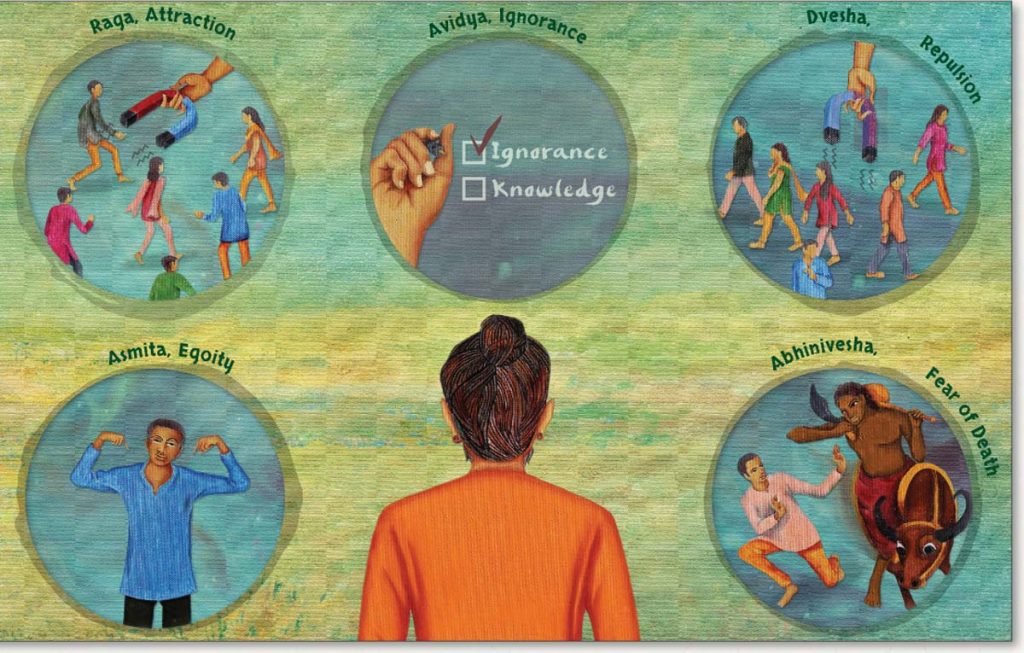

Patanjali called the things that cause us to suffer kleshas, or obstructions. He named five of them. The first, avidya, is that we do not fully know who we are. Avidya is often translated as ignorance. The ignorance it refers to is that, while we might know a lot about many topics, we do not fully know who we truly are. It is this incompleteness of knowing that allows four other kleshas to arise: a false narrative about who think we are (asmita); our likes and dislikes (raga and dvesha); and clinging to life (abhinivesha).

Several years ago I became fascinated by the question of why, if yoga was for the removal of avidya and other kleshas, did we need to do physical things like asanas and pranayama? The kleshas are basically mental misperceptions. How could a physical practice change something on the level of the mind? Why not work with the mind directly? Most people have experienced that the mind is very difficult to work with directly—meaning it’s difficult to control—because when we think of our mind we think of it as being composed of thoughts, and thinking often can get out of control. We ruminate, become compulsive, imagine scenarios that may never happen; and each time we engage in these thoughts we imagine that they are real. Thinking something to be real that is not real is called a misperception, and misperception is intimately tied into the reason why we do not know, fully and truly, who we are.

In the Yoga Sutras, thoughts are not the mind, thoughts are activities that occur in a neutral field called chitta. Those activities are thoughts, emotions, sensations, information and memory. Called vrittis, they form the basis of our identity, but, as the often-used analogy goes, they are just ripples on the surface of the ocean, not the depths of ocean or the entirety of the ocean itself. One of the ways that the ocean expresses itself is through currents, ripples and waves; one of the ways that the field of chitta expresses itself is through ripples and waves that make up the form of our body and nervous system. So, to work first with our bodies, and the things that make our body go, is to calm the ripples, so we can experience the depths of the ocean, so to speak, the source of being.

In the first section of chapter two of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, we find a selection of about twelve aphorisms that discuss kriya yoga, the actions in yoga that thin or reduce the obstructions or afflictions of the mind (the reasons we suffer) and prepare us for the inner radiance of samadhi. Kriya means action, and the kriyas are the indirect actions in yoga that accomplish the above stated results. Why indirect? Because the direct action of samadhi, outlined in chapter one, addresses a mind that is fit for one-pointed focus already. But what about the rest of us, who are prone to semi-distracted states of mind? Those who can focus for a while, but then find our minds wandering off to different states of distraction. What can we do to move towards deeper states of yogic contemplation? We can do the kriyas. Patanjali defines three of these:

Tapas: practices pertaining to the physical body, such as asanas, pranayama and the restrictions of the yamas.

Svadhyaya: repetition of mantras, study of sacred texts and self-evaluation.

Ishvara Pranidhana: surrender to God or any conception of the Divine.

These practices are prescribed by Patanjali to thin the kleshas, the obstacles, which are critical enough to deserve a deeper discussion.

The Five Kleshas

Quotes on the Kleshas

“One of the strange but ever-present states in all beings is the desire to live forever. Even those in the presence of death every day have this illogical desire. This is what inspires the instinct for self-preservation in all of us.”

Sri TKV Desikachar,

Reflection on Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

“The means of Samadhi and the attenuation of Klesha is Kriya-yoga, i.e., calmness of the body and the senses through Tapasya, the predisposition to realization through Svadhyaya, and the tranquility of mind through Ishvara-pranidhana.”

Swami Hariharananda,

The Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali

“In the Yoga Sutras, 1:24, Patanjali says: “The Lord (Ishvara) is untouched by [the five] kleshas (troubles), karma (action), vipaka (habit), and ashaya (desire). Since the Lord is free from these eight imperfections inherent in creation, the yogi who seeks union with God must likewise first rid his consciousness of these obstacles to spiritual victory.”

Paramahamsa Yogananda,

God Talks with Arjuna, The Bhagavad Gita

Avidya, as mentioned earlier, is an incomplete knowing of who we are. Vidya is knowledge, and the syllable a indicates, in this case, the opposite. If vidya is knowing, then avidya is a not-knowing, misperception or mis-cognition. It is not total ignorance, for indeed we know many other things, but we do not know our true nature. Avidya is the ground for all of the other kleshas. In fact, it could be said that there is really only one klesha, avidya, because contained within avidya are the other four, which do not exist independently of avidya.

Asmita is the misidentification of identity and creation of narratives that occur when we do not truly know who we are. Asmi means “I,” and ta means “-ness” or “the quality of.” Asmita is the limited identity of a constructed self. When we have an incomplete picture of who we are, we fill in the blanks with peripheral identities, stories and false narratives that we spend our lives enforcing, defending and concretizing. This narrative constructs itself by holding on to likes and dislikes.

Raga and dvesha are our attachments to likes and dislikes, the things that we are attracted or drawn to (raga) as well as to the things to which we are averse (dvesha). They are both attachments. We are attached to the things that we find superior, and no less attached to the things that we find inferior or distasteful. The attachments to the things we dislike are often more troubling than the things we like. For example, if we are fans of one sports team, that can set us against every other team in the league. Attachment to one team makes us averse to twenty.

Abhinivesha is clinging to life and the fear of extinction that occurs when all we know is our story, desires and aversions. When we take them to be real, we fear that without them we will cease to exist. Hence, the clinging to life, the clinging to our constructed narratives, the clinging to raga and dvesha. On a biological level, life perpetuates itself. The impulse to procreate, for example, is nature’s tight grip on its perpetuation. Since this is an impulse that is intrinsic to creation, it naturally flows in all beings, even, as Patanjali says, in the wise.

Through the practices of kriya yoga, all of these, we are told, will weaken their hold on us. The kleshas are like a covering over the light of our inner awareness. When that covering is thinned, the light of awareness shines more brightly through the covering, through the veil, and that pulls us inwards towards the radiance of samadhi. But the question is, how? How will a headstand, how will a breath held in pranayama, how will the simple repetition of a mantra reduce my fear of death? How will those practices change my false narrative about my life based on my fleeting desires. How will they remove all traces of my stories so that the only story left is the story of no story at all, of pure consciousness?

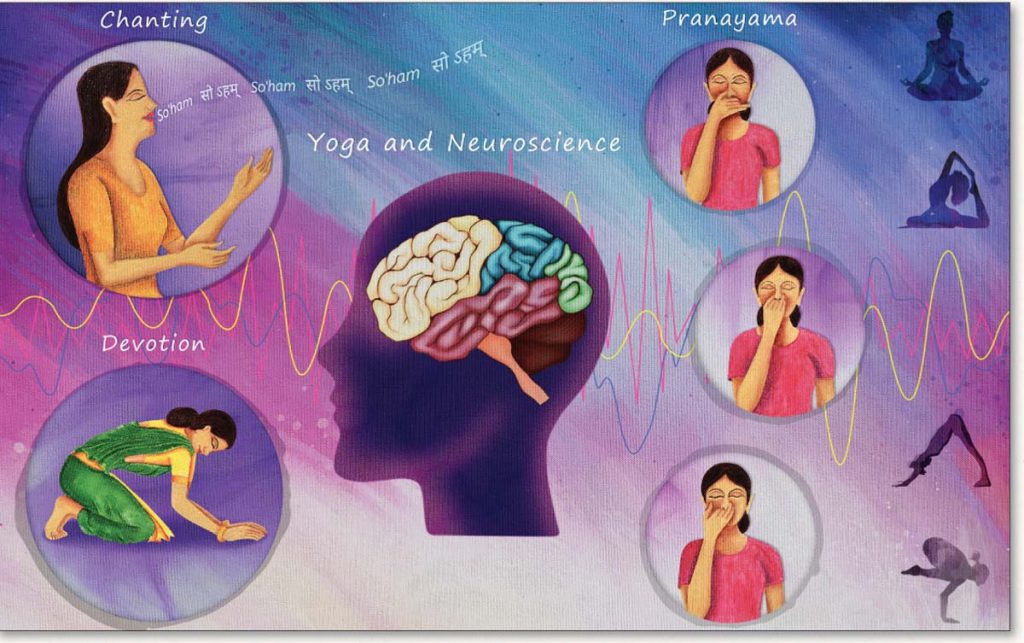

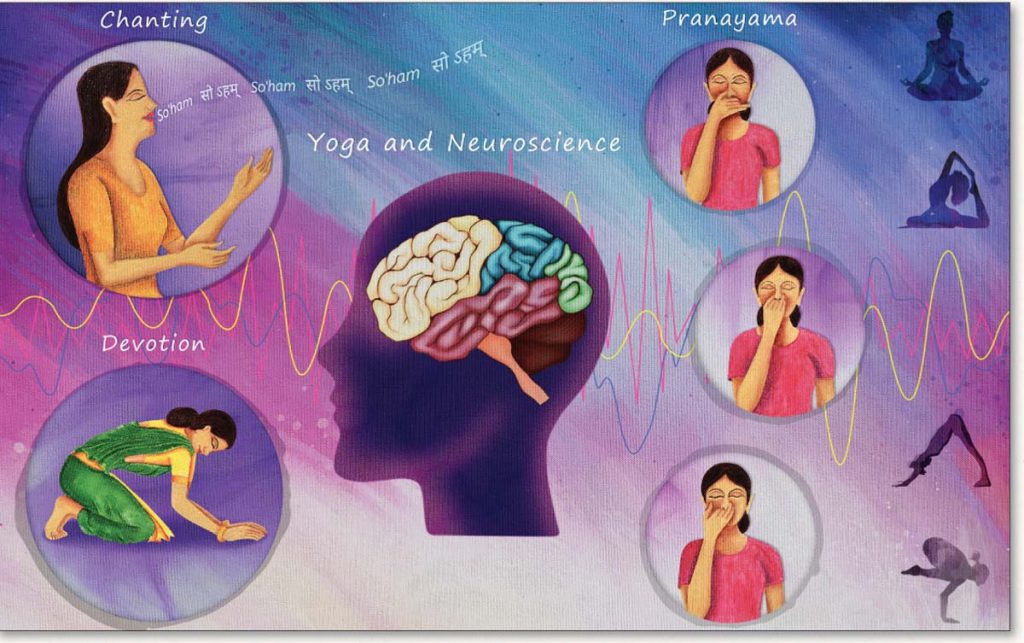

Yoga and Brain Functions

I wondered if I could look to Western neuroscience for clues on how, by working directly with the nervous system, we could pave a pathway to samadhi. I had an inkling through my studies of the autonomic nervous system—and in particular of homeostasis (the body’s innate ability to restore itself to balance)—that deliberate practices that restrained autonomic, physiological processes were a starting place for exploring how we could override habitual, unconscious responses to the world and move into deeper states of expanded awareness. The basic functions of the nervous system are described in very similar ways by Western scientists and yogis. The yogic conception makes use of something called prana, which has a multitude of meanings depending on context. Prana means “that which causes things to move.” It exists on a macro and micro level. On a macro level, prana creates and upholds order in the cosmos. On the micro level of the body it performs the functions that keep the body moving and in a constant symbiotic relationship with the world it lives in (such as breathing and temperature change). Prana is called by different names depending on the functions it performs, though it nevertheless remains one thing. There are five primary expressions: prana (incoming nourishment), apana (outgoing waste), samana (assimilation), vyana (distribution), and udana (outward expression).

These five processes are involved with every interaction we have, internally and with the external environment. In regards to breathing: prana is our inhalation; apana the exhalation; the exchange of gas at the level of the alveoli is samana; distribution of oxygen to every cell of the body is vyana; and speech, hiccups, coughs, sighs and yawns are udana. In regards to eating: prana is incoming food; apana is outgoing waste; samana is digestion; vyana is the distribution of nutrients; and udana describes the actions we express outwardly in the world because we are nourished. These five processes describe how the world we live in sustains us, which is another way of seeing the world as our extended, physical body. The description of prana in the yoga texts is varied in regards to detail, but cohesive in the explanation that it is prana that powers us. When prana leaves the body, our life as we know it is over.

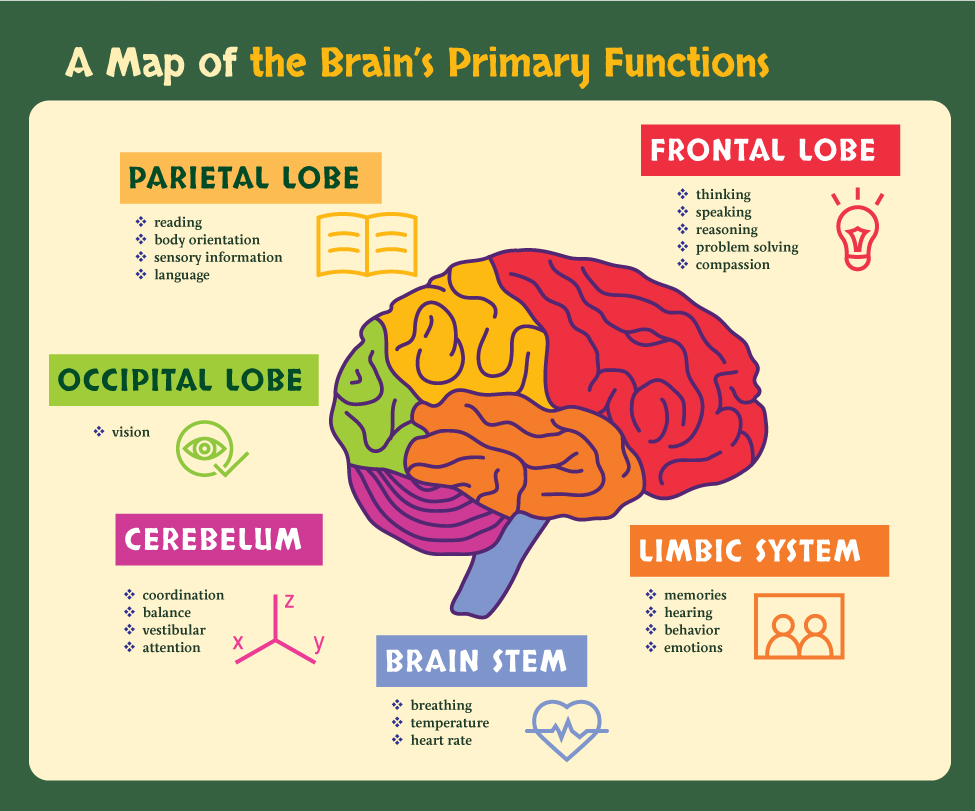

The Brain Stem, Abhinivesha

According to Western science, the mechanism that controls these same physiological functions in our body is the nervous system. The brain stem houses what are collectively called the survival functions, the things that our body does automatically, so we don’t have to think about doing them to stay alive. These automatic, or autonomic functions, include regulating respiration, heart rate, digestion, elimination, sleep, sexual reproduction and maintaining body temperature and blood pH. If we had to think about consciously doing any of those things, we wouldn’t be able to survive. We couldn’t eat if we had to think about breathing or beating our heart, and we certainly couldn’t sleep if we had to think about sleeping—just thinking about it would keep us awake! It could be said that the entire purpose of the brain stem and our survival functions is to help us to cling to life, in a most literal sense. Thus, on one level abhinivesha, clinging to life, is the foremost job of the brain stem. While this is not explicitly stated in Yoga Sutras, there are an abundance of hints that speak about nervous system functions in different ways. For example, sutra 1.30 speaks of sickness, laziness, sensual preoccupation and failure to be consistent in practice as obstacles to a calm mind. Sutra 1-31 says these obstacles show themselves as shaking of the limbs, disrupted breathing (both ruled by the nervous system), and anxiety, which is also the sympathetic nervous system’s response to a perceived environment. The body is the receiving-end organ of mental and emotional impulses; meaning, what happens in the mind happens in the body. Therefore, it follows that by steadying the body through practices of restraint, calmness and challenges, the upstream, subtle receiving organ of the brain and all that it processes (including our thoughts) will be influenced, steadied, as well.

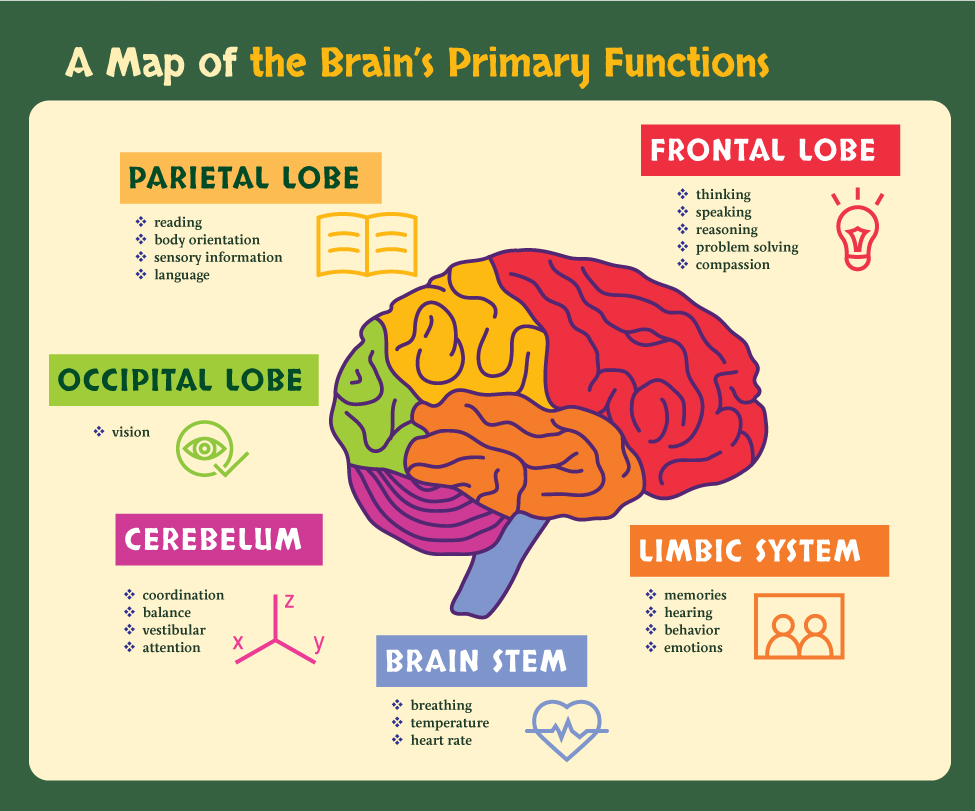

While the brain processes information and is the central control mechanism for our life, it does not cause existence to happen, or cause us to be. When scientists study the brain and make statements such as “the prefrontal cortex is responsible for our executive functions,” what they are saying is that decision making, language, long-term planning, compassion and other higher-level functions are processed and organized through this area of the brain. We do not know where the impulse to survive, to live, came from, but somehow, hundreds of millions of years ago, single-celled organisms had the impulse to move away from danger and move towards safety. That impulse exists within us in our brain stem, and is about 360 million years old. Other structures of our current brain makeup developed later, such as the limbic system and prefrontal cortex.

If the brain stem’s purpose is to maintain life functions, to literally cling us to life, where could we, theoretically, see the other kleshas represented in the brain?

Limbic System, Raga and Dvesha

The limbic system is in the middle portion of the brain. It is made up of centers that process fear, emotions and memory. Raga and dvesha, our likes and dislikes, attractions and aversions, are both learned and instinctive. Through exposure to environment and the creation of habits that our parents and education expose us to, we develop habitual tendencies that draw us towards some things and away from others. For example, imagine that one day your parents bring you, as a child, to an amusement park and buy you an ice cream. It’s the best thing you’ve ever tasted. But while you are taking your first bite, your parents wander off and you get lost. The taste of the ice cream and the fear of being lost become linked, and somehow through that trauma, the taste of that one flavor of ice cream always reminds you of being lost in an amusement park when you were five. While some attractions and aversions are learned through experience and exposure, others we are somehow born with, and we do not know where they come from.

Interestingly, the brain’s pleasure centers, the fear centers and the memory centers are all close to each other. Current scientific research on this is extremely complicated and fascinating. Neuroscientists Kent Berridge and Morten Kringelbach examined where “liking” and “disgust” are processed in the brain and published their findings in Neuron Journal in 2015. They discussed how the regions of the brain that are associated with reward-liking, wanting, sensory pleasures, disgust and fear in regard to external stimuli interact with higher-level brain structures such as learning, so that we can actively strategize to move towards pleasure rewards and away from things that disgust us or to which we are averse. Interestingly, this overlap in neural circuitry with the prefrontal cortex is associated with higher-level pleasures beyond sensory pleasures. The concept of “liking” is associated with the limbic system, and is described as an adaptive response to existence. Our likes and dislikes, even on this neuroscientific level, serve our existence, or our will to live. Abhinivesha is the support of raga and dvesha.

The Frontal Cortex, Asmita and Avidya

That leaves us with asmita and avidya. The cortical region of the brain is the uppermost area. It processes information relating to the executive functions: language, reasoning, strategic planning, pro-social engagement and the expression of compassion, empathy and philosophical contemplation, among other functions. It is in this region of the brain that we can ponder philosophical conundrums such as the distinctions between fate and free will, theodicy, the nature of our conscious and unconscious actions in the world, and the countless other contemplations that philosophers, yogis and seekers have dwelled on for thousands of years. The prefrontal cortex is related to conscious states of awareness, as well as directed states of awareness, while brain stem functions are largely subconscious and automatic. The ability to consciously direct our awareness, which is the basic description of what is happening when we practice yoga, is a prefrontal cortex operation.

Scientists Christopher Koch and Francis Krick have attempted to identify neural correlates of consciousness, and therefore conscious experience. They propose these correlates are located in the posterior part of the cortex, and that conscious experiences are made sense of, to some degree, in the frontal regions of the cortex, helping to turn the experiencer into the “owner” of that experience. Hence, a story is created by ownership and identity. This is asmita, or I-ness, the narrative we create when we identity the experiences we have as occurring to us. The default mode network, the area of the brain that is active in a restful, waking state, is associated with day dreaming, rumination and, according to the literature presented by Dr. Eva Svoboda, activates when we recall episodic and autobiographical information, self-reflection and semantic processes. Each of these processes is intrinsic to the constructed I-sense that is described as asmita, the first of the kleshas that arises from avidya.

And so what of avidya, the incomplete knowing of who we are? According to Patanjali, it is through the conscious directing of focused awareness and non-engagement with arising memories and thought patterns that we can begin to unravel our misperceptions. We use the power of self-awareness to experience that we are aware. Then that awareness of awareness is a movement inward to places that neuroscience cannot yet describe, but that the yogis have, and in detail. In regards to the brain, this process of consciously directing our awareness towards quiet occurs in the prefrontal cortex.

Bringing It All Together

Let’s come back to kriya yoga to pull this all together. The components of kriya yoga, as mentioned earlier, are tapas, svadhyaya and Ishvara pranidhana.

Tapas

Swami Hariharananda Aranya, in his commentary on Vyaasa’s bhashya on the Yoga Sutras, states that tapas is physical, svadhyaya is verbal and Ishvara pranidhana is mental. The practices of tapas include asanas and pranayama, which affect physiological functions. Asanas are done not just to make the body strong and flexible, but to exert a deliberate pressure on internal organs and nerves that send messages directly to the brain, particularly the brain stem. For example, the gut-brain axis is the communication network of the microbes of the gut communicating through the vagus nerve (the primary nerve complex of the parasympathetic nervous system) back to the brain to tell the brain the condition of the gut. Many of the twisting asanas, and postures such as mayurasana are providing a deep stimulation to the abdominal viscera which are messaging directly to the brain.

The heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, stomach, diaphragm and intestines are all receiving messages from the brain, and also sending messages to the brain, through the vagus nerve. When we massage, stimulate and change pressure to these organs, when we encourage blood circulation and oxygenation to these organs, that message of life and vitality is sent to the brain. This keeps our operating system in balance, healthy and filled with vitality.

The health of the communication systems from the body to the brain stem supports homeostasis, the body’s ability to constantly restore balance in relationship to the changing environment that we live in. Thus, the physical practices associated with tapas are directly affecting brain stem functions. The yogis who can stop their heartbeat, stop their breathing, control their sleep, withstand either freezing or extremely hot temperatures, go without food for extremely long periods or digest anything they ingest, are controlling brain stem functions. This is tapas.

Svadhyaya

Svadhyaya is self-evaluation and the repetition of mantras. One of the key aspects of svadhyaya is bhavana, the devotional mood or emotion associated with spiritual practices. The experience of mood and emotion is tightly linked to the limbic system. Swami Hariharananda has stated that without developing bhavana, the deeper levels of meditation cannot occur. Through the practice of svadhyaya, we address the area of the brain that processes and cements the narrative we have created about ourselves based on fear and emotions. The likes, dislikes, attractions and aversions of raga and dvesha are cemented here as repeated, habitual responses to the constructed world we live in.

Ishvara Pranidhana

While the brain stem primarily performs operations for the sake of keeping us alive, the limbic system processes information that keeps the sense of identity alive, but an identity based not on Self-referral but the object referral of the constructed self. Fear, memory and emotions are all processed in the limbic system. They are responses to actions, experiences, impressions and the desires to either move toward or move away from one of those experiences.

The repetition of mantras and self-evaluation breaks the cyclical narrative we often have rolling through our heads, and replaces that narrative with the syllables of transcendent thought (mantras) and the ability to observe how and when our likes and dislikes rear their heads. We can train ourselves to slow down our physiological processes with tapas, and we can train the fiery reactivity of the limbic system through using cooling, devotional feelings to calm the turbulence of the emotional centers. When things are going too fast, they are harder to catch. So, the first step is to slow down. We then create conditions for the deeper practices of compassion, empathy and contemplation, all of which occur in the cortical region of the brain.

Ishvara pranidhana, which is surrender to the Lord, or the perfect alignment of our awareness with the Seer within, could potentially be correlative for the information processing at the cortical level of the brain, as it requires the conscious directing of our awareness. Surrender is a purposeful not-knowing of what the future will bring, and a trust that whatever does happen is for the best. Ishvara pranidhana bypasses philosophical thought, to some degree, through surrender and devotion, and maximizes the two practices into a one-pointed flow of mental modifications; so we could surmise that bhavana is also associated with the prefrontal cortex.

If tapas is an undoing of solely identifying on a physical level, and svadhyaya is an undoing of our constructed narrative identity, then Ishvara pranidhana is the inward movement of awareness towards the Seer within. It is the utter relaxation into the arms of the Lord, to rest on the bed of Anantadeva, the serpent bed who represents the infinite folding in and out of time. As this final process is intentional, the area of the brain where intentional thought is processed lies in the prefrontal cortex. The higher-level behaviors discussed in the yoga texts—such as compassion, generosity, kindness, friendship, forgiveness and discipline—all occur in the prefrontal cortex.

It has been shown in studies on monks and yogis in deep meditation that there is a harmonious flow of brain-wave activity—whole-brain signaling—that occurs at deep stages of meditation.

The observable patterns of brain-wave activity simply reflect the electrical activity of information flows in the brain, blood flow and oxygen absorption, and these activities are driven by thought—so that something imperceptible causes a perceptible activity—whether those meditative thoughts are non-specific awareness, focused attention, compassion-based practice or repetition of a mantra. Certain types of thoughts will direct blood flow to targeted areas of the brain; this is what brain imaging is measuring. However, the deepest levels of meditation show a coherence of brain-wave patterns, a fully integrated coherence that transcends our normal, fractured waking and dreaming states. Yoga is a process of mastering and intentionally constructing new patterns of awareness within our body-mind complex. The ultimate goal is kaivalya, which the absence of all patterns; freedom is to be free of all patterns, no matter how pure or elevated a pattern may seem. We can use the ingredients nature has given us in order to be free from all patterns.

My Question Answered

It turns out, in answer to my earlier question, that the body can indeed be the starting place for freedom, and asanas are the easiest way to begin. We just have to be careful that we do not stop or get stuck on asanas, because then identification with the body will become stronger, and with it, all of the issues of asmita, egoity, as well. When we engage practices beyond asanas, we have more tools to consciously reflect on our own personal patterns, troublesome as well as positive, on our journey towards liberation.

Science can help, simply because it is another tool for measuring whether or not the techniques are doing what we hope they will. It can be encouraging to see that we have the power to slow our heart rate, decrease high blood pressure, slow down brain wave patterns to deep sleep states even while awake, maintain constant body temperature in extremely cold weather or control anger and food habits. The encouragement we feel inside of ourselves from experiencing these things leads us to have a faith based on conviction, called shraddha, that fills us with vitality, or virya. This vitality and energy increases our memory, smrti, so that we constantly recall that, yes, we should always remember to practice, because we are on the right path. This constant remembrance leads to deep levels of mental absorption, called samadhi, and from these deep levels of absorption comes insight, or intuition, into the deepest recesses of our being. This is the sequence as described by Bhagavan Patanjali: shraddha virya smriti samadhi prajna purvaka itaresham (1.20). The prajna that arises from within strengthens our shraddha again, and so the entire mechanism works as a closed-loop feedback system. Patanjali’s yoga describes the deliberate steps we can take to work towards this attainment, and modern science and the understandings of brain functions can help us to understand on a very practical level what occurs physiologically when we engage in the various yoga sadhanas. The kleshas do indeed have physiological correlates, because the mind and body are a continuum of patterns. When we free one, we free the other.

About the Author:

Eddie Stern is a yoga instructor and author from New York City. His latest book is One Simple Thing, A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How it Can Change Your Life, and his newest app is “Yoga365, micro-practices for an aware life.” His daily, live yoga classes can be found on www.eddiestern.com