One balmy evening in Ubud, Bali visitor Rima Xoyamaygya looked out her hotel window: “Streaming by me were 300 children and adults joyfully carrying offerings to a temple festival. A gamelan orchestra played alongside in a truck, and all traffic was stopped. This was my happiest experience on Bali.”

Miguel Covarrubias wrote in 1937 that offerings “are given in the same spirit as presents to the prince or friends, a sort of modest bribe to strengthen a request; but it is a condition that they should be beautiful and well made to please the Gods and should be placed on well-decorated high altars.” These devotional creations are stunningly showcased in the coffee-table book Offerings, The Ritual Art of Bali (160 pages, Image Network Indonesia), with lavish photos by David Stuart-Fox and accompanying text by Francine Brinkgreve. The following is excerpted from the book:

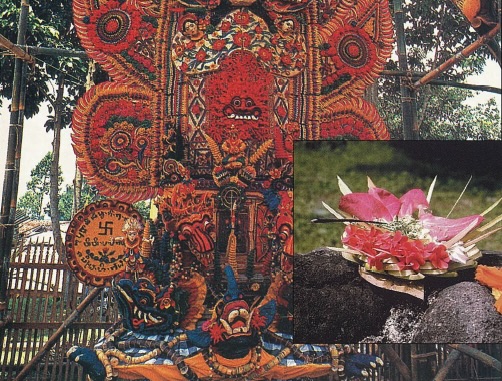

Except for once a year, no day passes without offerings, found everywhere. Each day the lady of the house places little flower-laden palm leaf containers on a family shrine. A driver places a similar offering on his dashboard. Families graciously carry towers of fruits and cookies to a temple on its anniversary day. Whole villages sometimes create enormous offerings meters high. Within offerings, wondrous details like rice dough figurines and delicate palm leaf creations are nearly hidden from view.

An offering is the most important means of maintaining good relations with Gods and demons. When presented to the Deities, it expresses gratitude and thanks for Earth’s fertility, for everything making life. When offered to the demons, it prevents them from disturbing universal harmony. An offering presented to souls of the deceased helps them in their journey toward reincarnation.

So important in helping to maintain the continual renewal of life in Bali, an offering has a life cycle of its own. Its ingredients are the fruits of the Earth, and stay fresh only for a couple of days. Beyond the ephemeral nature of the materials themselves, the gift is transitory by intention: once offered it may not be offered again. Made one day, gone the next, only to be recreated again and again, it symbolizes the hope that nature itself will continue to renew its fruitfulness.

After daily food is prepared and before a family starts eating, Deities, ancestors and demons receive their share in the form of many tiny offerings consisting of small pieces of banana leaf with rice and salt. Every day, too, they are given little offerings called canang, palm leaf containers with colorful flowers and the ingredients for chewing betel: betel leaf, areca nut and lime. Apart from these basic daily offerings, the complex Balinese calendrical system requires more elaborate ones on many special days, such as full and new moons and temple festivals. Gods and ancestors receive their offerings on high shrines whereas demons get theirs on the ground.

Offerings also serve to cleanse or purify, or act as a kind of seat for the invisible beings witnessing the ceremony. Some offerings are more decorative, such as the sarad, a spectacular structure only seen at major festivals, consisting of a bamboo framework several meters high, totally covered with brightly colored cookies made of rice dough. Balinese certainly have no qualms about displaying their devotion in grand style.1Ú4

IMAGE NETWORK INDONESIA, JALAN DANAU TAMBLING 108, SANUR 80228, BALI, INDONESIA. FAX: 011-361-287-811