By Richard Thornhill

The substantial sums of Hinduism that Buddhism carried along on its historic spread across Asia is not always appreciated. Indian Mahayanist philosophers, such as Nagarjuna, directed Buddhism back towards Hinduism, away from the rigid atheism of Theravada Buddhism. It was Mahayana Buddhism that spread to China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam. As a result, some of the earlier schools in Japan, such as Shingon, Kegon and Tendai, had largely Hindu pantheons. In addition, the Mahayana scriptures are in Sanskrit, unlike the earlier Theravadin canon, which is in Pali, and numerous Sanskrit inscriptions can therefore be seen in Japanese temples, and sometimes on rocks in the mountains. Japanese folk religion is a rich mélange, but a number of Hindu Gods play an important role. For example, of the seven Gods of good fortune whose temples people visit at New Year, three are Hindu: Daikoku (Mahakali), Bishamon (Vaishravana) and Benten, Benzaiten or, most formally, Bensaitensama (Sarasvati). A popular temple at Futako Tamagawa, Tokyo, displays Ganesha far more prominently than the Buddha.

Sarasvati is one of the first Deities recorded in Hinduism, being mentioned numerous times in the Rig Veda, as the sacred river on the banks of which the Veda was inspired, and as the Goddess who is “inciter of all pleasant songs, inspirer of all gracious thought” and “best mother, best of rivers, best of Goddesses.” Sarasvati is now usually seen as the shakti of Brahma, and the patron Goddess of the arts, learning and music. She is usually shown playing a vina, and sometimes with four arms.

In Japan, Benten is usually shown, rather similarly, as a beautiful woman dressed in the robes of a Chinese aristocrat, playing a biwa (a kind of lute) and wearing a jewelled crown. As such, She is instantly recognizable from thousands of television and magazine advertisements, and is perhaps the most well-known Japanese Deity. More specifically religious pictures often show Her with multiple arms. She is the Goddess of music, cultured learning and the entertainment-related arts, and also of rivers and water. Most of Benten’s temples and shrines are on islands, in rivers and streams, ponds and lakes, or near the sea.

From ancient times, Benten has been identified with the Shinto Goddess of islands, Itsukushima-Hime or Ichikishima-Hime, a minor figure in the oldest Shinto scriptures. In 1870, Shinto and Buddhism were legally separated, and the Shinto clergy have thus stressed this identification so as to continue worshipping Benten at jinja (Shinto temples). Just as in the Rig Veda Sarasvati is viewed as one of a trinity of Goddesses, together with Ila and Bharati or Mahi, in the Shinto classics Itsukushima-Hime is one of a trinity of water Goddesses, together with Tagori-Hime and Tagitsu-Hime, all of whom were formed from the sword of the Sun Goddess. This trinity is worshiped at the Munakata Jinja near Fukuoka, and also at subsidiary jinja.

Although Sarasvati is a river Goddess, Itsukushima-Hime is identified with the offshore island of Miyajima, and Benten is therefore sometimes considered to be a sea Goddess. However, all the marine islands dedicated to Her are close to the land, often joined by bridges or causeways, and the area of tidal flow thus seems to have replaced the flow of the river. She is sometimes associated with fishing and sea travel.

Benten has from ancient times been known as Uka-no-Kami in Japan and as the Dragon God in China. She is worshiped as the water Goddess, who is the womb of all things in the universe, and of all reproduction and development. She is the Goddess of happiness and good fortune who blesses business and productivity, controls the fertile harvests of the five cereals and their manifold increase, and brings all things to birth. She is also known as Myoonten (fine music Deity), Bionten (beautiful music deity) and Gigeiten (fine arts Deity), and is widely revered as the Goddess who enables the striving for excellence in arts, crafts, technology, music, literature and religion. It all sounds very much like Saraswati.

Benten is associated with dragons and snakes, especially white snakes. There are numerous stories of Her taking the form of a snake, or marrying a giant snake or sea-dragon, and She is sometimes shown as a human-headed snake or a coiled snake. In Japanese myth and folklore the dragon is associated with rivers and the sea, and in Taoist thought it represents the forces of nature. It is thus possible to understand Benten as the immanent aspect of divinity in nature. Then, if one understands Brahma to be the transcendent aspect of divinity, the perception of Sarasvati as immanent accords well with Her being His shakti. This makes it possible to see the East Asian nature-oriented religions of Shinto and Taoism as Goddess-oriented forms of devotional Hinduism.

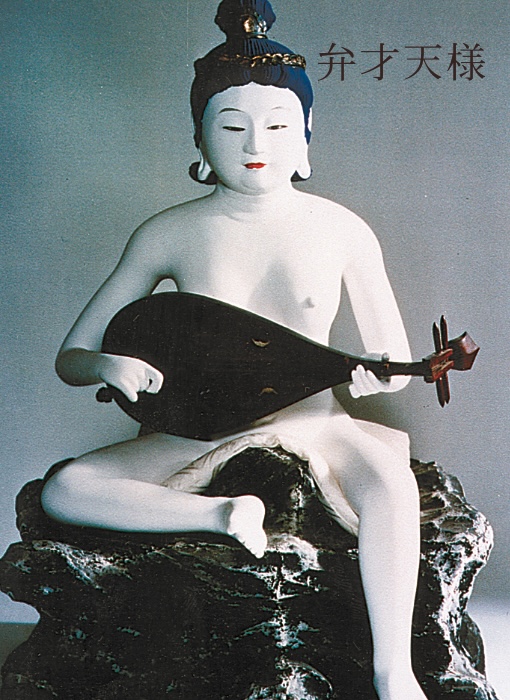

Japan’s three most important Benten jinja are Enoshima, Itsukushima and Chikubushima. The small island of Enoshima, connected by a bridge to the mainland near Kamakura, is dedicated to the Munakata trinity. In the jinja there are two statues of Benten, both more than 600 years old, of which one is unclothed and the other eight-armed. The unclothed Benten is milk-white, plays a biwa, and is carved in great detail. She is popular with female entertainers, such as geishas in the past and actresses and pop singers today. The eight-armed Benten holds a sword, a dharma wheel and various other items found in Hindu iconography.

The small island shrine of Itsukushima or Miyajima is a short ferry ride from Hiroshima. The torii—ornate jinja entranceway with sloping sides and flat top, painted red—on the beach is one of Japan’s most famous sights. Tame deer roam the island. The sacred island of Chikubushima in Lake Biwa has both jinja and Buddhist temples to Her. The lake is sacred to Benten because it is shaped like and named after Her biwa.

There are countless other Buddhist and Shinto shrines and temples in Japan. Among the hills above Kamakura, Zeniarai Benten is in a cave with a stream flowing through it. “Zeniarai” means “penny-washing,” and people believe that washing coins there will make them multiply. Deep in the recesses of the cave is a statue of Benten in the form of a snake with a human head.

Other shrines near Tokyo include the temple at Shinobazu Pond, Ueno, in central Tokyo and at Inokashira Pond at Kichijoji (meaning “Lakshmi Temple”), in the western suburbs. It has a Bentendo on a small island reached by two bridges. At Shakujii, a couple of miles north of Kichijoji, there is Sanpoji Pond, with Itsukushima Jinja on a small island at one end, surrounded by lotuses. The pond is one of the sources of Shakujii River and used to be a place of annual pilgrimage for the rice-farmers living along its banks. For centuries it has been taboo to hunt or collect timber, plants or fuel in or around the pond, and it is now an outstanding nature reserve. At a fork in the road near Shinjuku, Tokyo, there is the tiny Nuke Benten or Ichikishima Jinja, a tiny island surrounded by goldfish-filled ponds. Hakone Jinja on Lake Ashi is a favorite weekend destination for Tokyoites. In the grounds there is an exquisite pond full of carp, with a small Benten shrine on a mossy rock in the middle. There is no bridge, but the floor of the pond is covered with coins thrown in as offerings. At all these shrines, one can sense the continued presence of this Goddess who came from India to bless this land of the rising sun.

AuthorRichard Thornhill, PhD, lives in Tokyo, where he works as a translator. E-mail him at r-n-thornhill@aa.bb-east.ne.jp