Exploring the Genius of India’s Guru-Shishya System of Spiritual Training and Transmission

From the Teachings of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

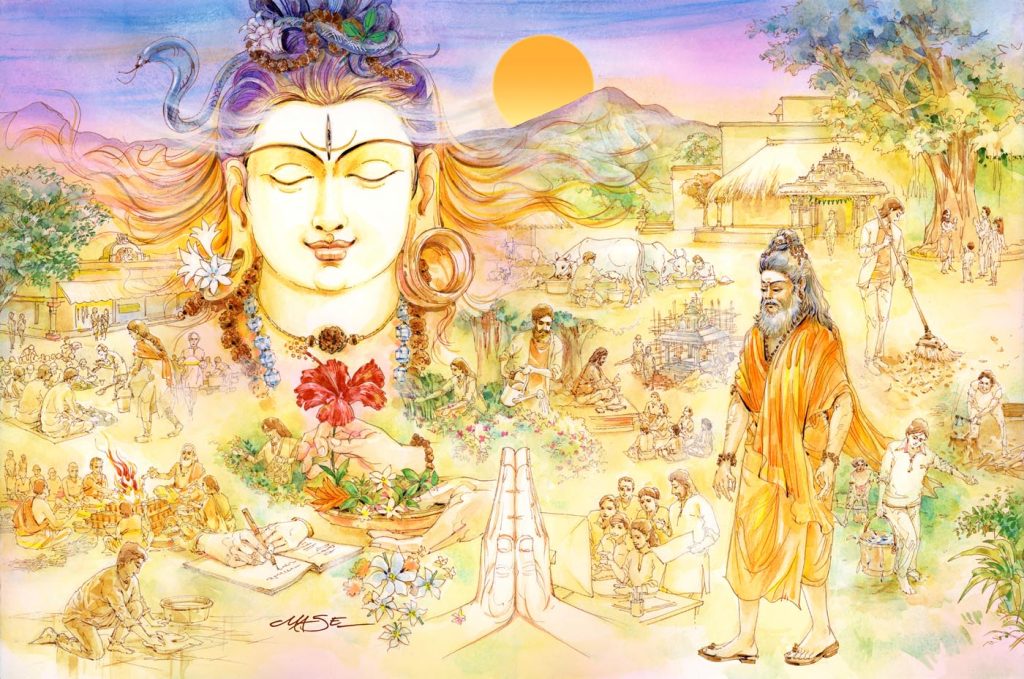

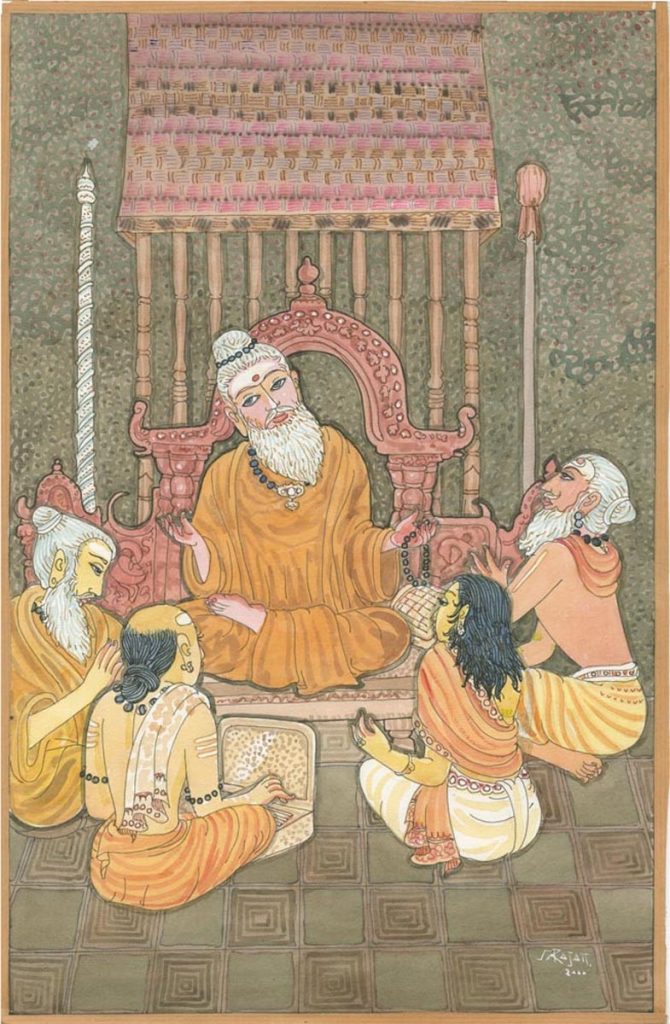

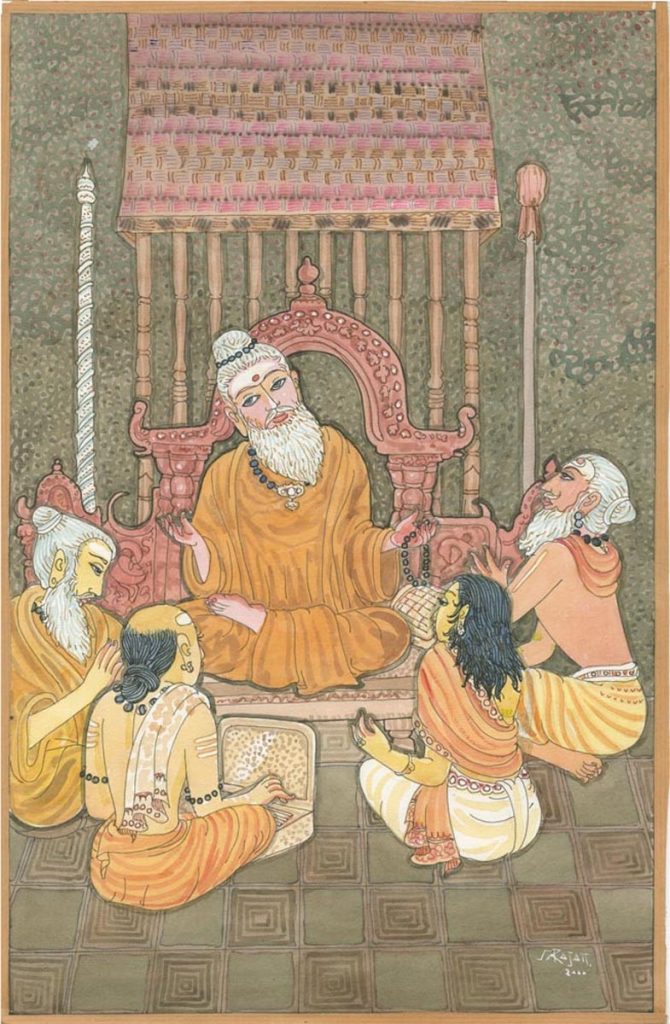

With Essays by Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD • Art by Maniam Selven

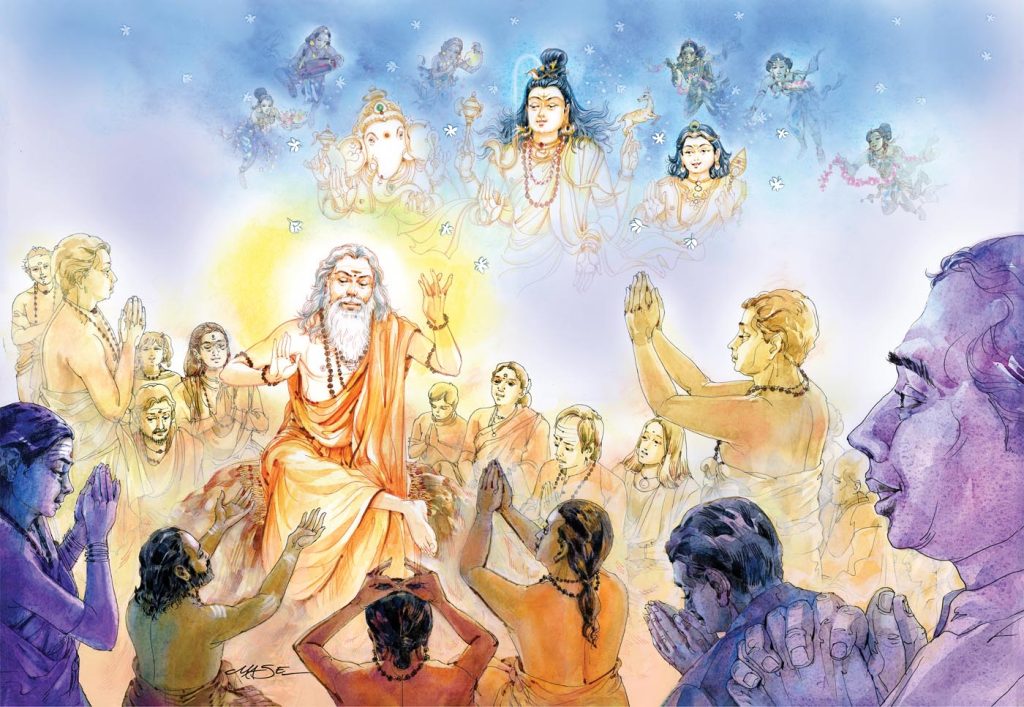

When the soul has had enough experience, it naturally seeks to be liberated, to unravel the bonds. That begins the most wonderful process in the world as the seeker steps for the first time onto the spiritual path. Of course, the whole time, through all those births and lives and deaths, the soul was undergoing a spiritual evolution, but unconsciously. Now it seeks to know God consciously. That is the difference. It’s a big difference. By this conscious process of purification, of inner striving, of refining and maturing, the karmas come more swiftly, evolution speeds up and things can and usually do get more intense. Don’t worry, though. That is natural and necessary. That intensity is the way the mind experiences the added cosmic energies that begin to flow through the nervous system.

So, here is the soul, seeking intentionally to know, “Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going?” A path must be found, a path that others have successfully followed, a path that has answers equally as profound as the seeker’s questions. In Saivite Hinduism, we have such a path. It is called the Saiva Neri, the Path of Siva. It is a wide and unobstructed path that leads man to himself, to his true Self that lies within and beyond his personality, lies at the very core of his being.

I want to speak a little about this inner path today. You all know that it is a mystical path, full of mystery. You cannot learn much of it from books. Then where to look? Look to the holy scriptures, where the straight path to God is described by our saints. Look to the great masters, the siddhas, or perfected ones. Look to the satgurus, who have themselves met and overcome the challenges that still lie ahead for you. Look to them and ask them to help you to look within yourself. Much of the mysticism which is the greatest wealth of Hinduism is locked within these masters, who in our tradition are known as the satgurus, the sages and the siddhas. There is much to say on this. As Yogaswami told us, “The subject is vast and the time is short!”

The Necessity of a Guru

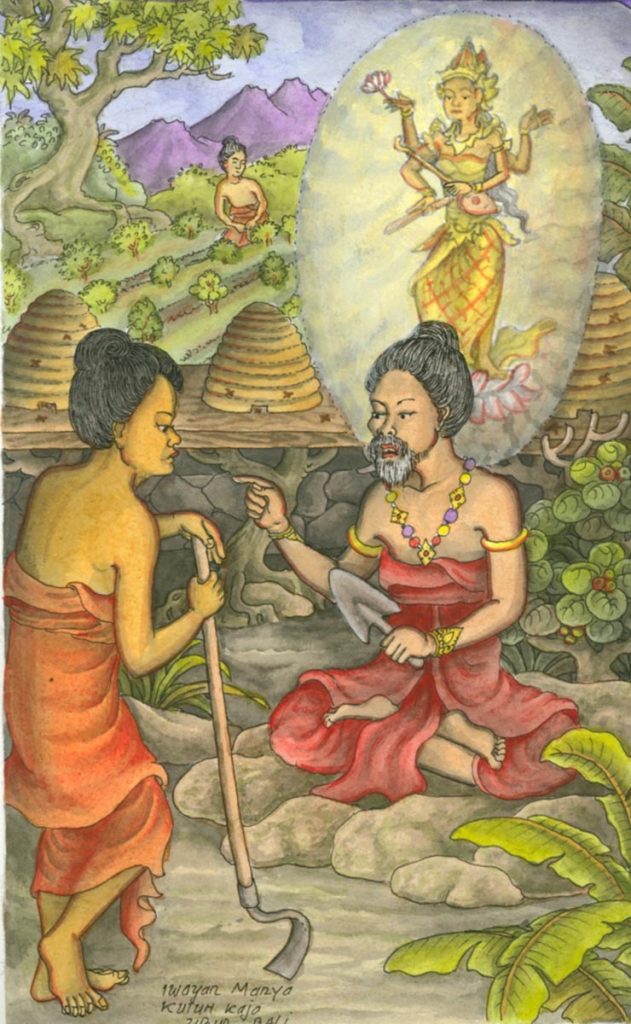

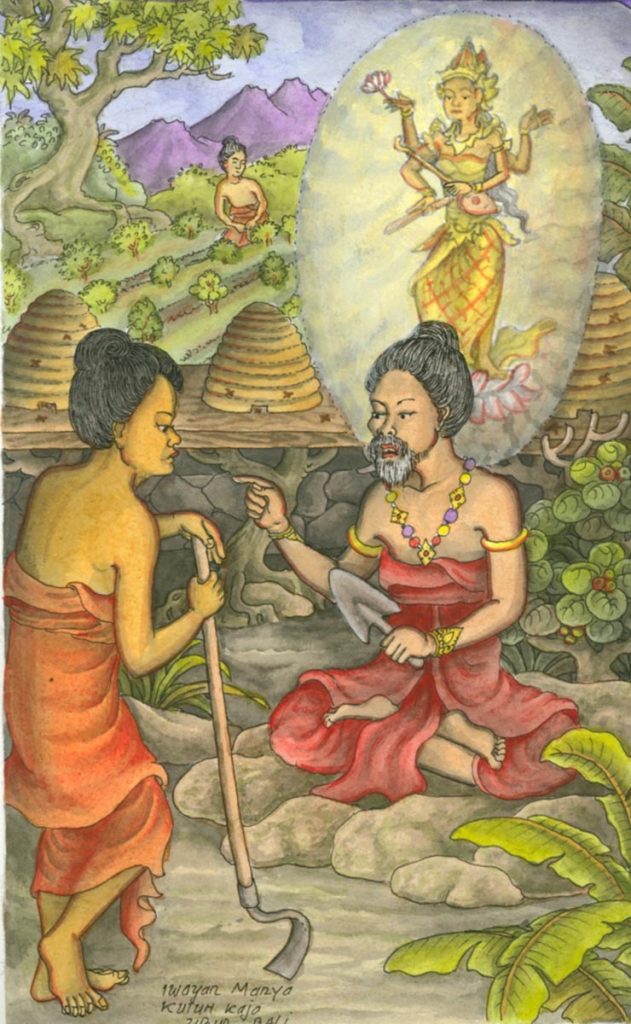

It is said in our Hindu scriptures that it is necessary to have a satguru. However, it is also possible for an individual to accomplish all of this by himself without a guru. Possible, but most difficult and exceedingly rare. There may be four or five in a hundred years, or less. Scriptures explain that perhaps in past lives such a soul would have been well disciplined by some guru and is helped inwardly by God in this life. With rare exceptions, a guru is necessary to guide the aspirant on the path as far as he is willing and able to go in his current incarnation. Few will reach the Ultimate. The satguru is needed because the mind is cunning and the ego is a self-perpetuating mechanism. It is unable and unwilling to transcend itself by itself. Therefore, one needs the guidance of another who has gone through the same process, who has faithfully followed the path to its natural end and therefore can gently lead us to God within ourselves. Remember, the satguru will keep you on the path, but you have to walk the path yourself.

All gurus differ one from another depending on their parampara, their lineage, as well as on their individual nature, awakening and attainments. Basically, the only thing that a guru can give you is yourself to yourself. That is all, and this is done in many ways. The guru would only be limited by his philosophy, which outlines the ultimate attainment, and by his own experience. He cannot take you where he himself has not been. It is the guru’s job to inspire, to assist, to guide and sometimes even impel the disciple to move a little farther toward the Self of himself than he has been able to go by himself.

It is the disciple’s duty to understand the sometimes subtle guidance offered by the guru, to take the suggestions and make the best use of them in fulfilling the sadhanas given. Being with a satguru is an intensification on the path of enlightenment—always challenging, for growth is a challenge to the instinctive mind. If a guru does not provide this intensification, we could consider him to be more a philosophical teacher. Not all gurus are satgurus. Not all gurus have realized God themselves. The idea is to change the patterns of life, not to perpetuate them. That would be the only reason one would want to find a satguru.

Some teachers will teach ethics. Others will teach philosophy, language, worship and scriptures. Some will teach by example, by an inner guidance. Others will teach from books. Some will be silent, while others will lecture and have classes. Some will be orthodox, while others may not. The form of the teaching is not the most essential matter. What matters is that there be a true and fully realized satguru, that there be a true and fully dedicated disciple. Under such conditions, spiritual progress will be swift and certain, though not necessarily easy. Of course, in our tradition the siddhas have always taught of Siva and only Siva. They have taught the Saiva Dharma which seeks to serve and know Siva in three ways: as Personal Lord and creator of all that exists; as existence, knowledge and bliss—the love that flows through all form—and finally as the timeless, formless, causeless Self of all.

When we go to school, we are expected to learn our lessons and then to graduate. Having graduated, we are expected to enter society, take a position comparable to our level of education. We are expected to know more when we leave than when we entered, and we naturally do. When we perform sadhana, we are expected to mature inwardly, to grow and to discipline ourselves. And, in fact, we do become a better, more productive, more compassionate, more refined person.

But when we perform yoga, we are expected to go within, in and in, deep within ourselves, deep within the mind. If yoga is truly performed, we graduate with knowledge based on personal experience, not on what someone else has said. We then take our place among the jnanis—the wise ones who know, and who know what they know—to uplift others with understanding in sadhana and in yoga.

Guru Loyalty

A devotee on the path who has a satguru should not seek darshan from another guru unless he has permission from his own guru to do so. Why? Because he should not become psychically connected with the other guru. The darshan develops inner psychic bonds. Another guru does not want to influence the unfoldment of the aspirant either. However, if he has permission to absorb darshan from someone else, then of course, there has been an inner agreement between the two gurus that no connection will result, and the disciple will not be distracted from his sadhana by conflicting new methods.

It is not good for a student on the path to run around to various teachers and lecturers and gain reams of miscellaneous knowledge about the path and related occultism. He becomes magnetically attached to the students of the various teachers and sometimes to the teachers themselves. The teachers do not like this “browsing” on the part of the guru-hopper either, for it impairs the unfoldment of their own students, as it goes against the natural flow of unfoldment on the path. It is also energy draining and time-consuming for the guru or swami.

One must look at spiritual unfoldment in the same way one approaches the study of a fine art. If you were studying the vi∫a with a very accomplished teacher, he would not appreciate it at all if you went to three or four other teachers at the same time for study behind his back. He demands that you come and go from your lesson and practice diligently in between. By this faithful and loyal obedience, you would become so satisfied with the results of your unfolding talents that you would not want to run here and there to check out what other maestros were teaching and become acquainted with their students. Students run from teacher to teacher only when they do not obey the teacher they have.

Harmony with the Guru

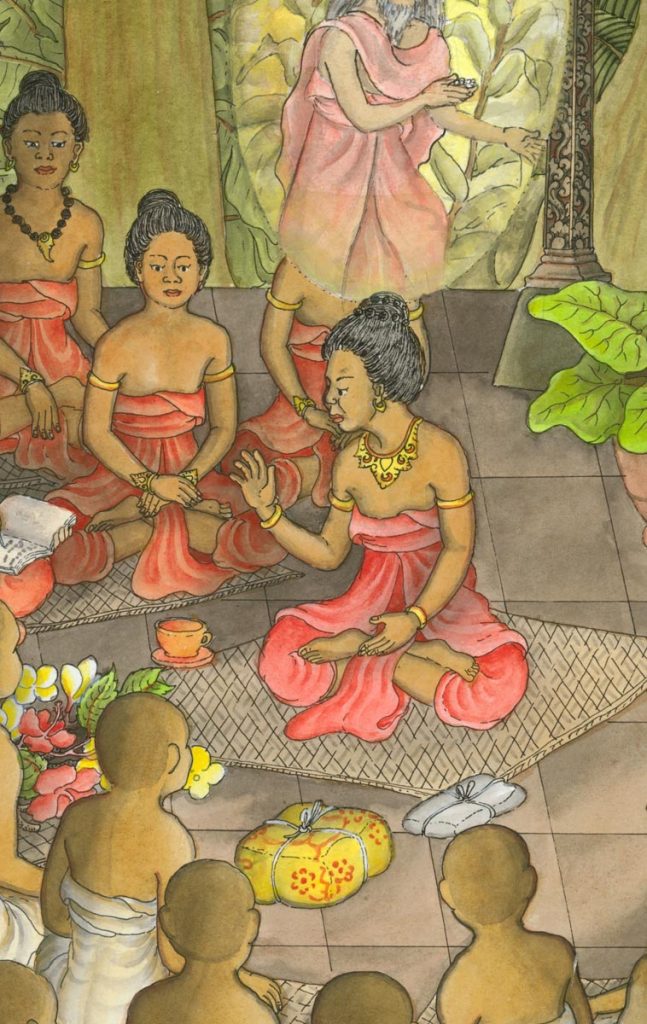

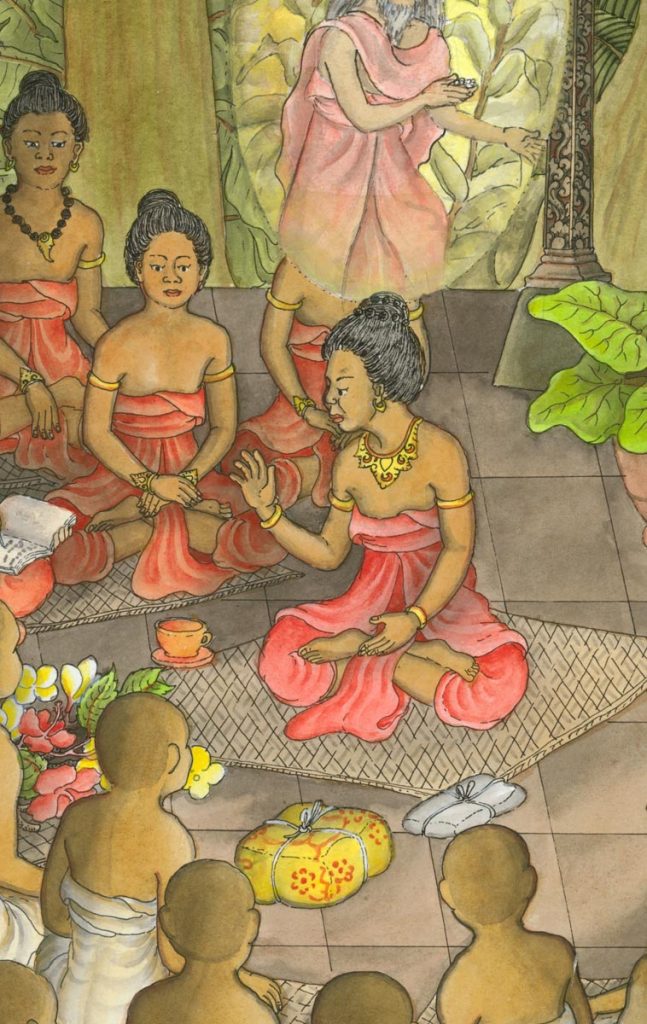

Before books were invented, the traditional way of conveying information was through the spoken word. This is called sampradaya. Sampradaya, verbal teaching, was the method that all satgurus used. A satguru can only give his shishya as much as the shishya can hold in his mind at any one time. If the shishya comes with an empty cup, the cup is filled by the guru. But if the shishya comes with a cup that is already full, nothing more can be added by the guru.

Many satgurus work with their devotees in unseen ways. They have the ability to tune into the vibration of a devotee anywhere his physical body might be on the planet, feel how he is feeling and send blessings of protection and guidance. The guru-shishya system of training is personal and direct. Much is unspoken between them, so close is the mental attunement. The traditional observance of brahmacharya helps to stabilize this relationship.

An advanced shishya is one whose intuition is in absolute harmony with that of his satguru. This harmony does not occur in the beginning stages, however, when the devotee is probing the subject matter of the guru’s teachings for answers. Only after he has conquered the fluctuating patterns of the thinking mind does an inner flow of harmony begin to become apparent to both guru and shishya. The shishya is expected to cultivate his inner life as well as his outer life. The more sincere and consistent he is with his inner work and his inner friends—God, Gods and guru—the more safe and secure and blessed he will be. Your relationship with your guru is growing stronger even now as you come to better know yourself and proceed in your study of these daily lessons.

Responsiveness

It is the duty of the shishya to be responsive to the satguru and not resistive. I was impressed at an ashrama in India we visited recently with how responsive everybody was to their guru. The guru there merely looks, and devotees ask, “What can I do to serve?” The guru speaks, and everyone immediately responds. No resisting: “I have something else to do. You already gave me ten things to do. How can you possibly want me to stop now and do something else? Isn’t there somebody else around here who can do it?” I saw none of that there. Maybe everybody was just on their good behavior because we were there, but it certainly took a lot of practice. They must have been practicing to be on their good behavior for about five years before we arrived. Wonderful responsiveness. Because of such responsiveness, the connection between the shishya and the guru maintains a systematic growth, and the spiritual life comes up within the individual which breaks all routine and yet works within routine, is beyond all intellectual and reasoning abilities yet works within the intellect and through reason, is unpredictable yet predictable in that it is consistently unpredictable.

However, we must remember that blind obedience is never the spiritual way. It is intelligent cooperation that is the binding force in a well-run ashrama. Intelligent cooperation means obtaining an extremely clear understanding of what is requested to be done before proceeding. Often this requires asking questions, discussing the direction or project, as one would do in a modern corporation, then, once all is understood, making the leader’s direction your own direction. This is intelligent cooperation, not blind obedience.

The World as Guru

There are three kinds of gurus that are traditionally available to guide the soul. The first, of course, are the parents. Next is the family guru, or a guru chosen by the children. The third guru, often the most suave, the most attractive, but in reality always the most demanding, is Vishvaguruji Maha-Maharaj. He does live up to his name in all ways, for vishva means “everything and everyone in the world,” and guru, of course, means “teacher.” Maharaj is “great ruler.” Vishvaguruji, as I call him, seemingly teaches so patiently, yet accepts no excuses and remains unforgivingly exacting in his lessons. Everyone living on this planet has a guru, whether they know it or not.

When the world becomes the teacher, the lessons can be rough or enticing, unloving or endearing, unpleasant or full of temptuous, temporary happiness. The world is relentless in its challenges, in the rewards it offers, the scars it leaves and the healing it neglects. The unrelenting Vishvaguruji works surreptitiously through the people you meet, as past-life karmas unfold into this life. He never gives direct advice or guidance, but leaves the lessons from each experience to be discovered or never discovered. His sutra is “Learn by your own mistakes.” His way of teaching is through unexpected happenings and untimely events, which are timely from his point of view. Unnecessary karmas are created while the old ones that were supposed to be eliminated smolder, waiting patiently for still another birth. Pleasure and pain are among his effective methods of instruction. Vishvaguruji is the teacher of all who turn their backs on parents, elders, teachers, gurus or swamis, laws and traditions of all kinds. It is not a lingering wonder why someone who once abandoned a loving guru or swami would want to return from the world and go through the vratyastoma reentrance procedures, no matter what it takes.

Those on the anava marga, the path of the external ego, often claim to be their own guru. Some untraditional teachers even encourage this attitude. However, being one’s own guru is a false concept. Traditionally, one would be his “own guru” only if he were initiated as such, and his guru left the physical body. Even then, he would be bound by the lineage within the sect of Sanatana Dharma he dedicated his life to, and would still maintain contact with his guruji within the inner world. Therefore, he would not really ever be his own guru at all. Being one’s own guru is a definite part of the anava marga, a very important part. It is raw, eccentric egoism. A teenager doesn’t become his own teacher in school. A medical doctor doesn’t become his own professor and then get a license to practice, signed by himself. Nor does a lawyer, an engineer or even an airline stewardess. So, logic would tell us that those pursuing something as sensitive, as personal and final as the path to perfection cannot on their own gain the necessary skills and knowledge to be successful in this endeavor.

Well, we are having fun here, aren’t we? But it is also a serious subject. Think about it. In the realm of training and responsiveness, we can say that there are two basic margas, or stages: the anava marga and the jnana marga. Those on the jnana marga know they need someone in their life who has already attained what they are seeking to attain, who can see ahead of their seeing and consciously guide them. This is the traditional path of Hindu Dharma leading to Self Realization.

Those on the way of external ego have met many teachers, tested them very carefully, and have found them all not meeting up to their standards. They are the devotees of Shri Shri Shri Vishvaguru Maha-Maharaj-ji, members of his Bhogabhumi Ashram, place of pleasure. The regular daily sadhana is stimulating the desire for sex, for money, for food, for clothing.

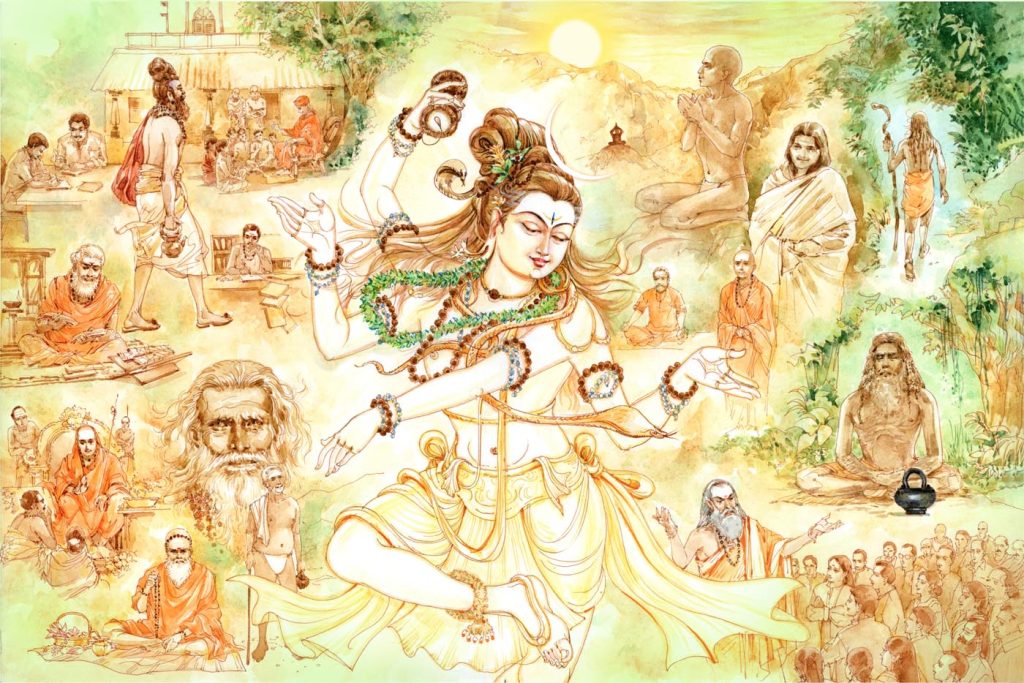

Spirit of Parampara

Hindu temples sustain Hinduism around the world. Scriptures keep us always reminded of the path we are on and the path we are supposed to be on, but only from the satguru can you get the spirit, the shakti, the sustaining spirit, to make it all come to life in you, to make the temple meaningful and to complement the scriptures with your own sight, your own third-eye sight. Otherwise, it’s just words…. It is that spirit of sampradaya that makes the traditional teachings meaningful, that gives you the power to discriminate between what is real within those teachings and what is superfluous or just plain nonsense, that gives you the power to blend Siddhanta with Vedanta, Vedas with Agamas. The irreversible spirit of the guru carries through all of the shishyas. It is basically the only gift a guru can give—that sustaining spirit. He doesn’t have to give knowledge, because that has already been written down. He doesn’t have to build temples, because there are more than enough temples for everyone. The rare and precious gift that he can convey is the inner spirit of his religious heritage. That is his unique gift to the world.

Nathas do not follow the way of words. Kadaitswami spoke to a lot of people. Who knows what he said? They didn’t have tape recorders in those days, and doubtless he never wrote anything down, but the spirit carried through him to Chellappaguru, who didn’t say an awful lot. He wasn’t following the way of words either. He spoke only divine essences of the philosophy. He didn’t write 3,000 verses like Rishi Tirumular did. Nor did he give lectures to crowds like Kadaitswami did. His spirit was passed on to Satguru Siva Yogaswami, who passed his spirit on to a lot of devotees. We must remember that during the time of the British, all gurus had to keep a very low profile and that Yogaswami’s great work started to flourish publicly only after the British left Sri Lanka. He passed his spirit on to lots of devotees, including me. If I had not journeyed to the northern part of Sri Lanka and gone to Siva temples, worshiped there and received initiation from Yogaswami, would I have returned to America and built a Siva temple or helped found over fifty other Hindu temples scattered around the world? No. Would we have a monastic community? No….

Only because of the existence of one satguru in this venerable line of gurus, I caught the spirit; and through this spirit the words manifest, the activities manifest, the devotees maintain that straight path, the disciplines bear fruit, the inner sight comes, and after it comes, it stays. Without satgurus, we would only have temples and scriptures. Without satgurus, we wouldn’t have the spirit, and people would stop going to temples and stop reading the scriptures.

A satguru doesn’t need a lot of words to transmit the spirit to another person; but the shishyas have to be open and be kept open. The little bit of spirit extends like a slender fiber, a thin thread, from the satguru to the shishya, and it is easily broken. A little bit more of that association adds another strand, and we have two threads, then three, then four. They are gradually woven together through service, and a substantial string develops between the guru and the shishya. More strings are created, and they are finally woven together into a rope strong enough to pull a cart. You’ve seen in India the huge, thick ropes that pull a temple chariot. That is the ultimate goal of the guru-shishya relationship.

Upon the connection between guru and shishya, the spirit of the parampara travels, the spirit of the sampradaya travels. It causes the words that are said to sink deep. They don’t just bounce off the intellect; the message goes deep into the individual. Spiritual force doesn’t just happen. It’s a hand-me-down process, a process of transmission, just as the development of the human race didn’t just happen. It was a hand-me-down from many, many fathers and mothers and many, many reincarnations that brought us all here. Parampara is a spiritual force that moves from one person to another. I am not talking about the modern idea of bestowing shakti power, where somebody gets a little jolt and pays a little money and that’s the end of the association with the teacher.

Parampara is like giving a devotee one end of a tiny silk thread. Now, if the devotee drops his end of the thread, the experiences are stopped and only words are left, just words, one word after another, another and another. The devotee then has to interpret the depth of the philosophy according to the depths of his inherent ignorance. What other measurement does he have? The relationship with the guru is a constant weaving in and out of one fiber of the thread added to another fiber, added to another fiber, added to another fiber, just like this khadi kavi robe we wear in our Order was woven. Each fiber is attached to another fiber, attached to another fiber, attached to another fiber, and finally we have a thread. Between the guru and shishya many threads are all woven together, and finally we have a firm rope that cannot be pulled apart or destroyed even by two people pulling against one another. That is sampradaya. That is parampara. That is the magical power of the Nathas.

Meeting My Guru

by Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD

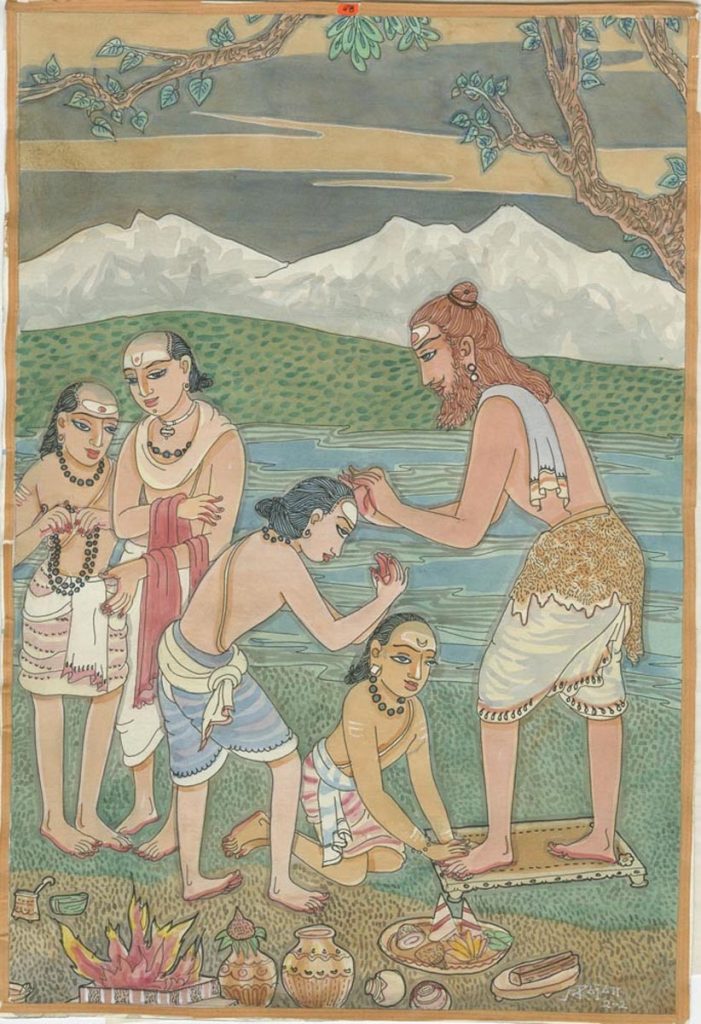

On September 26, 2021, I met with my guru in a private room at our temple. Several years earlier, in an earnest gesture of faith, I had sacrificed my beloved hair for tonsure, after having had beautiful long hair for over 30 years. Now, a neat shikha (tuft of hair) on the back of my head was all that was left of my mane. This symbolized that I was serious and ready to commit to spiritual life. I was wearing a spotless white dhoti and kurta, formal dress for a very special occasion. I was to be initiated as a brahmin (member of the “priestly class”) by my guru—His Grace, Vaisheshika Dasa Adhikari Maharaja.

I sat down before my guru, and he whispered the sacred gayatri mantras into my right ear, as gurus had done for disciples for thousands of years, in an unbroken connection to an unfathomable antiquity. Spiritual traditions derive their power and authority from the strength of their connection to the past, as an accretion of the wisdom accumulated by countless lives of sages and practitioners who are ever-shaping the tradition in each successive generation. Donned in white, I was now entering deeply into that stream.

My Guru Maharaja presented me with the sacred thread (upavita) of a brahmin, and instructed me on how I would use it to observe tri-sandhya, that is, recitation of the sacred mantras three times a day, before sunrise, at noon, and during the evening twilight. This practice has since become my spiritual axis around which my day revolves. I can hardly describe the joy of centering myself by stopping what I’m doing three times a day, and bringing my mind, body, speech, heart, and soul back to my connection to the Beloved Divine.

This was the cumulation of a six-year relationship that I had carefully cultivated with my Guru Maharaja. When I met him, I immediately knew that he was my guru for multiple reasons. I had asked several gurus a certain set of questions that were specific to my sadhana (“daily spiritual practice”) needs. He was the only one who knew exactly what I needed without hesitation. The result was instant; ever since the day I met him, my sadhana had increased dramatically. His presence in my life had made me more enthusiastic and inspired. That is a good sign that one has found one’s proper guru!

After our first meeting, I spent the required (by our tradition) year-and-a-half where we observed each other, he observing if I was ready for a deep spiritual commitment, and I ensuring that we were harmonious. There are few things more painful than having someone that one considers an important, even loved, mentor suddenly reveal that they have some views that are discordant with one’s core values. I had experienced that painful disappointment on other occasions with other mentors. Fortunately, many generations ago our tradition had taken appropriate measures to ensure that this wouldn’t happen by mandating a year-and-a-half waiting period so gurus and disciples can mutually observe each other. Happily, he and I seemed perfectly harmonious—and the enthusiasm that I was infused with by his presence in my life proved that he was the right guru for me.

I took an initial course and exam so that our religious order could ensure that I knew our teachings sufficiently to commit to them, and I received a preliminary initiation in 2017. I then took a much more difficult course which involved nearly two years of writing dozens of papers and taking scores of tests and exams to ensure that I had more depth in my understanding of our tradition, its theology, and its sacred texts. Finally, I was ready for that wonderful afternoon in September, 2021.

Diksha & Adhikarana

However, there was an entire lifetime that led me to this momentous moment, perhaps even many lifetimes. I had spent nearly 15 years studying various yoga traditions, living in ashrams in India, learning Sanskrit, and even getting a master’s degree in Buddhism, before the importance of seeking out a guru for initiation (diksha) came to me.

By early 2015, my hybridized religious identity had become increasingly centered on one particular Hindu tradition. I had begun a PhD program in Hindu Studies at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California, under the guidance of Dr. Rita Sherma who is well known in the academy for being an important preceptor, leader, initiator, and seminal thinker in her work of advocating for Hindu theology as an academic discipline. After meeting her, I knew that I had found perhaps the rarest of all gurus—a mentor and advisor who could help me navigate the turbulence of eking out a successful research project, and eventually, a successful academic career.

After five years studying Sanskrit at UC Berkeley, I realized that I wanted to help define what “Hindu traditions” means to practitioners in the modern era; how these traditions might speak to issues of global capitalism, environmental destruction, climate change, mass extinction; racial and ethnic marginalization, colonialism, gender and sexual oppression, and the horrors of modern animal agriculture (to name only a few). I wanted to use my voice as an insider in this burgeoning academic discipline of Hindu theology. With Dr. Sherma, I had found the perfect “academic guru.”

Doubtlessly, as an outsider to a given tradition, a scholar may know aspects of that tradition better than many—or even most—who practice it. But, since the majority of data to support religious truth claims come from firsthand experience, it is difficult, if not impossible, to access the data that supports the truth claims of any religious tradition as an outsider. Spectator objectivity can only take us so far in understanding religious truth claims. Objectivity excels at exteriority, but subjectivity is required for interiority, for essences.

While an “outsider” can have immense authority to “present” a tradition, they lack the authority, the adhikara, to “represent” the tradition by constructing meaning within a tradition, that is, defining what religious traditions means rather than what it simply is. Adhikara allows one to have greater access to the tradition in a more intimate way, in a firsthand way, as an insider.

In the vast traditions of Hindu Dharma—properly known as either Vedic Dharma, or Sanatana Dharma, or the “infinite (sanatana) harmonious order (dharma)” of personal, interpersonal and even cosmic reality—one attains such adhikara through initiation, or diksha. This means that one has surrendered to a guru. The importance of this “surrender” is evidenced by how many Sanskrit terms are used to describe it (sharanagati, prapanna, paridadati, pranidhana, etc.).

Discipleship as Austerity

Austerity has a peculiar connotation in English. Perhaps this is because Western cultural tendencies in modern times favor consumption. Consumerism is in complete opposition to austerity, which, in its most basic form, is restricting consumption (aparigraha), a practice that could go a long way towards addressing various forms of systematic violence in our modern society, such as global inequities of wealth, environmental destruction, animal exploitation, habitat loss, climate change, etc.

The basic definition of austerity, then, is the “generative power of voluntary discomfort.” Few people realize this power as directly as students, of any culture! When we study instead of indulging in recreation, we experience discomfort, and it produces something—intelligence, disciple, character, etc. This can be observed elsewhere in our lives: the austerity of employment whereby discomfort produces income, in social activism whereby discomfort produces social change and conditions of justice, in fitness whereby discomfort produces health and wellbeing, etc. Austerity (tapas), the generative power of voluntary discomfort, is one of the basic truths of the human existence, challenge, and improvement.

So it is for the disciple. The basic austerity of the disciple is service, or voluntary discomfort one engages in to discover knowledge. In that sense, one must earn knowledge. Likewise, in the modern academy, we have to serve the lineage of our discipline by showing due deference to the great thinkers of our disciplines, demonstrating mastery over their teachings, and enduring the constant austerity of having our work critiqued and rejected by scores of professors, peer-reviewers, tenure committees, etc. Before one is recognized at all by the academy, one has had to endure many years of severe discomfort for the right, the adhikara, to be a custodian and producer of our collective culture of knowledge.

While surrender can sound like one is giving up control, it simply means that one has faith that one’s guru knows something that one does not. It is not dissimilar in that regard to trusting authorities in any field, such as when one lays on the operating table “surrendering” oneself to the surgeon, or when one “surrenders” one’s car to a trusted mechanic, construction contractor, etc. Likewise, the first step in spiritual advancement, as in daily life, is admitting that there are those who know more than oneself about a certain topic, and having the intelligence to trust them and benefit from their wisdom that has likely been the accretion of knowledge over generations, tested by countless experts in their communities.

So it was in ancient India, where this principle seems to have been the same but the cultural context of the gurukula was different. There are a number of didactic parables illustrating this point in the Upanishads and other texts.

Perhaps the most poignant story regarding the relationship between austerity discipleship is that of Upakoshala Kamalayana. After twelve years of service to the same guru (Haridrumata Gautama) as Satyakama, despite a number of other disciples completing their studies during that time, he was still inadequately prepared. When the guru’s wife interceded on Upakoshala’s behalf, Haridrumata Gautama (the guru) simply left for a journey without instructing poor Upakoshala. Upakoshala then decided “to fast to address his mental anguish. ” He confesses to the guru’s wife, “Within myself there are various forms of desire. I suffer by a number of afflictions, so I will commence a fast” (Chandogya Upanishad 4.10.3). [Note: All translations herein are those of the current author.]

Fasting is an important and common form of austerity in dharma traditions. With fasting, we attempt to find a stability, and inner contentment, despite the challenge of experiencing an intensified desire for food. Here, fasting and food can be a synecdoche where food represents the desire for external sources of happiness, and fasting represents our resistance to that desire and seeking rather an internal source of contentment and satisfaction that is unmoved by external circumstances. The result is that we diminish the power that worldly desires have over us. However, any restrictions should be engaged in only if we are honest with ourselves in terms of what will be too much, otherwise we risk a dangerous backlash where desire will become uncontrollable and the results can be damaging—to our spiritual, mental, and/or physical health.

Satyakama seems to have achieved the desired result. His particular service to his guru was to attend to the sacred household ritual fires kept by brahmins. While fasting, in the process of engaging in this service, the sacred fires “spoke” to him, and instructed him regarding the nature of the Divine (CU 4.10.4-4.13.2).

Like with Satyakama, when the guru returned to find Upakoshala, he asked incredulously, “Your face is radiant as if you have understood the divine. Who has instructed you?” Upakoshala answered, “One who is other than human. Indeed, what here had seemed completely hidden now has instantly become otherwise. The sacrificial fires have made everything seem complete” (CU 4.14.2). The guru then adds one final teaching regarding how to realize the Divine, and how to do so when engaged in religious practice, ritual and mantra (CU 4.10-17).

With these parables, we see the common theme that through austerity, the student prepares themselves for the most esoteric teachings. But the preparation itself is almost as edifying as the actual instruction. With the austerity of the student life, the disciple learns discipline and is able to understand the deep wisdom in everyday actions. This includes the humility to engage in service to someone or Something greater than ourselves. For King Janashruti, that involved the realization that all of his worldly accomplishments were miniscule when compared to the wisdom and humility born of spiritual practices and austerity of his guru, Raikva. The brahmacarin who approached Kapeya Shaunaka and Kakshaseni Abhipratarin shows us that the true satisfaction and nourishment comes from spiritual wisdom rather than the pursuits of worldly comforts, and that we are deeply “fed” by the teachings of our gurus. From Satyakama Jabala we learn the importance of a disciple being truthful and honest even when we feel ashamed by who we are. Here, like with Koshala, we are taught that a great deal of spiritual wisdom is gained by the service itself.

he service attitude, which when adopted, allows us to see the wisdom of the natural world, animals, our daily rituals, and in other places, where we defer our comfort to the well-being and care of others—particularly those who hold the spiritual teachings which are the cultural treasures of humanity. If we, as disciples are to be like them (our gurus) one day—if we are to be custodians of ancient wisdom—then we must be prepared to experience difficulty in the hope that we will gain that which is far greater than worldly comfort.

As in our daily lives, with our spiritual lives we find that reward is proportional to the effort that comes from discipline. But while “discipline” implies restrictions, our fortitude in any discipline ultimately comes from a positive source: the degree of enthusiasm and inspiration that we bring to our spiritual practice. This is where a guru can perhaps be most beneficial.

From the Tirumantiram

1573: He taught me the meekness of Spirit, infused in me the light of devotion, granted me the Grace of His Feet; and after interrogation holy, testing me entire, revealed to me the Real, the Unreal and Real-Unreal. Of a certain is Siva-Guru the Lord Himself.

χ χ χ

1574: Gathering the strands of my fetters, He knotted them together and then wrenched them off; freeing me thus from my fond body, straight to mukti he led me—behold, of such holy potency is the Presence of the Guru Divine!

χ χ χ

1576: He is beyond worlds all yet, here below, he bestows his grace abundant on the good and the devout, and in love works for the salvation of all; thus is the Holy Guru, whose praise is beyond speech, like unto Siva, the Being Pure.

χ χ χ

1581: Guru is none but Siva—thus spoke Nandi; guru is Siva Himself—this they realize not; guru will to you Siva be, and your guide, too; guru, in truth, is the Lord that surpasses all speech and thought.

Guru Bhakti

from the Kularnava Tantra, chapter one

The Self is to be realized only here in this life. If here you do not find it and work out the means for your Liberation, where else is it possible? It is possible nowhere else. It has to be worked out by yourself from within yourself.

The world you reach after the physical body is shed is determined by the level of consciousness reached while in the body. So, as long as the body lasts, exert yourself towards the goal of Liberation. Remember, the physical body does not last forever. Age prowls like a leopard; diseases attack like an enemy. Death waits not to see what is done or not done. Before the limbs lose their vitality, before adversities crowd in upon you, take to the auspicious path. Therefore, choose, then worship a satguru. Worship his feet. Cherish the very sandals (paduka) which hold his feet. All knowledge is founded on those paduka. Remember and cherish those paduka, which yield infinitely more merit than any number of observances, gifts, sacrifices, pilgrimages, mantra-japa and rituals of worship.

Why the pains of long pilgrimage? Why observances that emaciate the body? All the fruit anticipated from such austerities can be easily obtained by motiveless service to the holy satguru. Therefore, bear your karma for the sake of the guru. Acquire wealth for the sake of the guru. Exert yourself for the guru, regardless of your own life.

Wisdom from Sri Chinmoy

Eternity’s Breath: Aphorisms and Essays

The Guru’s love for his disciple is his strength. The disciple’s surrender towards his Guru is his strength.

χ χ χ

It has become a fashion nowadays for people to say that there is no necessity of an intermediary between them and God, referring not only to the traditional priest, but also to the traditional Guru. Granted, but just tell me: did you receive any help in learning the alphabet? Did you require a teacher to help you master your musical instrument? Were you given instruction to enable you to obtain your degree? If you needed a helper to do these things, do you not also require a teacher who can guide you to the knowledge of the Divine, the wisdom of the Infinite? That teacher is your Guru and no one else.

χ χ χ

To achieve realization oneself and alone is like crossing the ocean in a raft. But to achieve realization through the Grace of a Guru is like crossing the Ocean in a swift and strong boat, which ferries you safely across the sea of ignorance to the Golden Shore.

χ χ χ

The real work, if there be any, of a Guru is to show the world that his deeds are in perfect harmony with his teachings.

Guru Urgency

from the Kularnava Tantra, chapter seven

Like a tigress, old age waits with open mouth to swallow the jiva. As water continually exudes from a broken vessel, so is the period of life constantly being shortened. Diseases constantly inflict wounds like enemies laying siege to a fortress. Hence one should, as early as possible, engage in the working of good to oneself and satguru. Good work should be done in times when there is no sorrow or danger, and when the senses are not disabled. The utmost period of one’s life is a hundred years. Half of it is passed in sleep, and the remaining half is made useless by childhood, disease, old age, sorrow and other causes. Utterly indifferent to the spiritual work which ought to be begun by all means, sleeping during the time he should be awake, and imagining danger when he should have firm faith—alas!

How can such a jiva, cherishing the fleeting samsara so dear to him, live without fear in this body which is as evanescent as a bubble of water, enduring no longer than the stay of a bird on the branch of a tree? He seeks benefit from things which do him injury, thinks the impermanent to be permanent, sees the highest good in that which is evil, and yet he does not see that death is coming upon him. Deluded by the great maya, the jiva looks and yet sees not, reads and yet knows not. The whole of this world is at each moment sinking into the deep sea of time infested with the great alligators of death and disease. We speak of “my son,” “my wife,” “my wealth” and “my friend,” but even as we indulge in such senseless talk, death seizes the body like a tiger. Therefore, jivas awakened to the path should be prompt in doing with all their heart such things as are calculated to benefit their satguru and themselves in this world and hereafter.

Guru Protocol

By Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD

The Manu Smriti (2.236) provides replete instructions in protocol of the student towards the teacher. It is important for a student to demonstrate the appropriate attitude when receiving the teachings so that the guru is not merely “casting the good seed” of knowledge “on a barren land” (MS 2.112). One should rather present oneself to the guru as if one is an asset, a treasure, to the guru (MS 114-115). This may include such respectful gestures as touching the feet of the guru before and after each lesson, and holding one’s hands in a respectful prayer gesture (brahmanjali) when receiving the lesson (MS 2.71-72).

When one is sitting in the presence of the guru, one should not occupy a seat that is higher or equal to that of the guru, but rather, one should be so seated as to be below the guru. One should arise when the guru enters the room (MS 2.117-119), and look at the guru in the face when one is being spoken to (MS 192). One should always be nicely dressed as well, and in general should “eat less, have less valuable dress and ornaments, rise earlier and retire later” than one’s guru (MS 2.194).

One should not engage in conversation with a teacher when reclining, eating, or with an averted face (MS 2.175), or generally sit too comfortably when in their presence (MS 2.198). One should always use the appropriate honorifics when speaking to or about one’s guru (MS 2.199), and one should leave the conversation if ever one should hear one’s guru being criticized (MS 2.200). And, of course, one should never censure or defame one’s guru (MS 2.201).

Some of the basic duties of an initiate include offering fuel on the sacred fire (like Koshala), sleeping on the ground, and in general doing what is beneficial for the guru (MS 108), such as fetching water, flowers, fuel and other amenities (MS 2.182). As we have seen, the various duties for disciples were intended for the development of the moral character and mental fortitude of the student.

Types of Gurus

By Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD

The term guru just means “teacher,” or literally “weight,” namely “one who has the weight of authority” based on their acceptance in a certain community of experts. One cannot just proclaim that one is an expert; one must be recognized as such by others in the same field of their expertise. Thus, we might have a great number of “gurus.” But, on the other hand, given the considerations of appropriation and cultural violence, it might be safest if we restrict the term guru to its traditional usage, namely, an expert and authority in the dharma traditions—Buddhist Dharma, Hindu Dharma, and Jain Dharma. (Dr. Sherma is a recognized authority within a Hindu tradition, so I feel it is appropriate to refer to her as my “academic guru.”)

However, not all gurus (even in the traditional sense) are those from whom we seek initiation. The early Hindu (or Vedic) traditions distinguished between two classes of teachers: the acharya and the upadhyaya. For example, Manu-Smrti (MS) states that the acharya is “ten times greater” than the upadhyaya. Some might consider the upadhyaya in the Vedic system to be more like a tutor and the acharya as the guru from whom one might seek initiation (Chaudri 2008, 39).

Different traditions will have different nomenclature to make the distinction between an initiating guru or diksha-guru, and one from whom we learn spiritual topics, such as shiksha-guru (“instructing guru”), shravana-guru (“a guru we listen to”), or upadhyaya (“teacher” or “preceptor.)”

Choosing a Guru

By Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD

The Manu Smriti gives the would-be disciple some good advice as to what constitutes a good teacher. These qualities are generally related to what behavior is appropriate for a brahmin in general. For example, the guru’s instruction should be centered on ahimsa, as “nonviolence to all beings is the highest duty. ” Reflecting this, their words should always be “gentle, sweet, pure, fair, and guarded when teaching that which is to be attained by Vedanta” (MS 2.159). They should not speak words that incite fear or cause pain or injury to others (MS 2.161), and should be humble to the point they even “fear praise and homage as if it were poison” (MS 2.162-163).

It is also important to ensure that one’s would-be guru doesn’t differ considerably from one’s core values; otherwise, it will be hard, if not impossible, to maintain the appropriate level of faith and respect in one’s guru that is required for proper instruction.

Bibliography

Chaudhuri, Rachita. 2008. Buddhist Education in Ancient India, Kolkata: Punthi Pustak.

Chatterjee, Mitali. 1951. Education in Ancient India. Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. 2001. The History of Education in

Ancient India. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.