A Simple Overview of a Complex Faith

BY THE EDITORS, DRAWN FROM THE TEACHINGS OF SATUGURU SIVAYA SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI

A recent Google search on “What is Hinduism” yielded some 223,000 answers. Many are from outsiders offering their best take; many are from antagonists taking their best shot. Too few are knowledgeable; fewer still are authentic. Rare is the answer that goes beyond parochial sectarian understandings; scarcely any encompasses the huge gamut implied in the question. For these reasons alone, the book from which this article is taken was inevitable. Written by devout Hindus and drawn from the deepest wells of spiritual experience and cultural insight, it is a definition coming from deep inside the inner sanctum and depicting in words and amazing images the living, breathing entity that is Hinduism. The founder of HINDUISM TODAYmagazine, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (1927–2001), well understood the challenges that all religions face in today’s world, whether from outside or within. He wrote that every religion consists of the spiritual precepts, practices and customs of a people or society, transmitted from generation to generation, that maintain the connection with higher realms of consciousness, thus connecting man to God and keeping alive the highest ideals of culture and tradition. Gurudeva, as he was affectionately known, observed that if this transmission misses even one generation, a religion can be lost for all time, left to decay in the dusty libraries of history, anthropology and archeology. He strove to protect the religion he loved so dearly. He would ask rhetorically, “Where are the once prominent religions of the Babylonians, Egyptians, Aztecs, Mayans, American Indians or Hawaiians?” Little remains of them. Not long ago it was feared by some and hoped by many that Hinduism—the religion of a billion people, one sixth of the human race, living mostly in India—would meet the same fate. That it survived a history of religious conquest and extermination that wiped out virtually every other ancient religion is exceptional.

Ironically, this noble faith, having withstood the ravages of invasion, plunder and brutal domination by foreign invaders for over a thousand years, stumbled into the 20th century to meet the subtler forces of secularism and the temptations of materialism. Christian propaganda, fabricated by 16th-century Jesuit missionaries, empowered by the 19th-century British Raj and carried forth today by the Western and Indian media, had dealt heavy blows over the centuries to the subjugated, prideless Hindu identity. A typical Christian tactic was to demean the indigenous faith, impeaching it as rife with superstition, idolatry, antiquated values, archaic customs and umpteen false Gods. India’s Communist/secular media stressed caste abuse and wretched social ills, branding as radical, communal and fundamentalist all efforts to stand strong for anything Hindu.

Most recently, safeguarding the anti-Hindu mind-set, Western professors of Asian studies brandished the tarnished term Hindutva to suppress pleadings by Indian parents to improve the pitiful portrayal of their faith in the textbooks their children must study in American schools—a portrayal that makes them ashamed of their heritage. More than a few Hindus, succumbing to the avalanche of ridicule, gave up their faith, changed their names to Western ones and stopped calling themselves Hindu, giving more credence to the notion that this is a faith of the past, not the future. Even those who were Hindus in their hearts would demur, “No, I’m not really a Hindu. I’m nonsectarian, universal, a friend and follower of all religions. Please don’t classify me in any particular way.” In a further dilution, many swamis and other leaders promulgated the false claim that Hinduism is not a religion at all, but a universalistic amalgam of Vedic, yogic wisdom and lifestyle that anyone of any religion can adopt and practice without conflict. Tens of thousands who love and follow Hindu Dharma avoid the H word at all costs. Rare it is to find a spiritual leader or an institution who stands courageously before the world as a Hindu, unabashed and unequivocal.

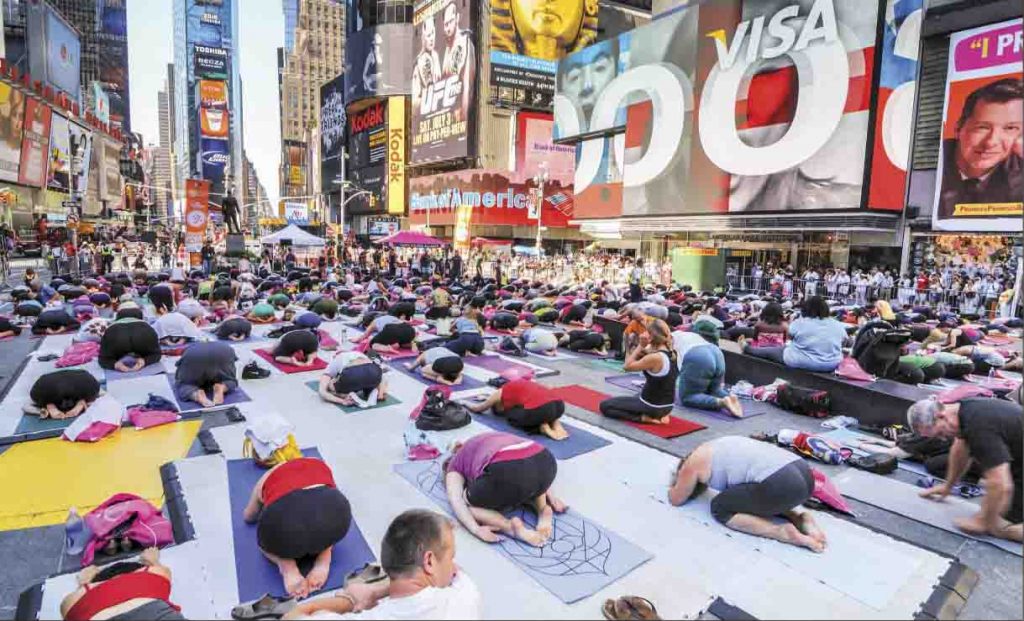

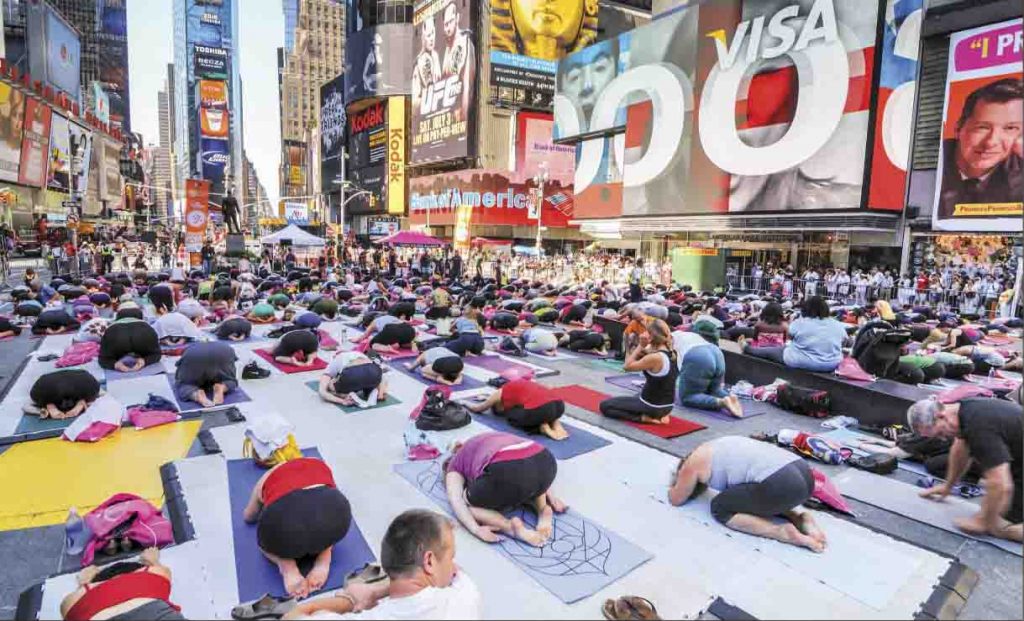

Despite these erosive influences, an unexpected resurgence has burst forth across the globe in the last twenty years, driven in part by the Hindu diaspora and in part by India’s newfound pride and influence. Hinduism entered the 21st century with fervent force as recent generations discovered its treasures and its relevance to their times. Temples are coming up across the Earth by the thousands. Communities are celebrating Hindu festivals, parading their Deities in the streets of Paris, Berlin, Toronto and Sydney in grand style without worrying that people might think them odd or “pagan.” Eloquent spokesmen are now representing Hinduism’s billion followers at international peace conferences, soft-power meetings, interfaith gatherings and discussions about Hindu rights. Hindu students in high schools and universities are going back to their traditions, turning to the Gods in the temples, not because their parents say they should, but to satisfy their own inner need, to improve their daily life, to fulfill their soul’s call.

Hinduism is going digital, working on its faults and bolstering its strengths. Leaders are stepping forth, and parents are striving for ways to convey to their children the best of their faith to help them do better in school and live a fruitful life. Swamis and lay missionaries are campaigning to counteract Christian conversion tactics. Hindus of all denominations are banding together to protect, preserve and promote their diverse spiritual heritage.

The Law of Karma Precept Number One

For Hindus and non-Hindus alike, one way to gain a simple (though admittedly simplistic) overview is to understand the four essential beliefs shared by the vast majority of Hindus: karma, reincarnation, all-pervasive Divinity and dharma. Gurudeva stated that living by these four concepts is what makes a person a Hindu.

Karma literally means “deed” or “act” and more broadly names the universal principle of cause and effect, action and reaction which governs all life. Karma is a natural law of the mind, just as gravity is a law of matter. Karma is not fate, for man acts with free will, creating his own destiny. The Vedas tell us, if we sow goodness, we will reap goodness; if we sow evil, we will reap evil. Karma refers to the totality of our actions and their concomitant reactions in this and previous lives, all of which determines our future. It is the interplay between our experiences and how we respond to them that makes karma devastating or helpfully invigorating. The conquest of karma lies in intelligent action and dispassionate reaction. Not all karmas rebound immediately. Some accumulate and return unexpectedly in this or other births. The Vedas explain, “According as one acts, so does he become. One becomes virtuous by virtuous action, bad by bad action” (Yajur Veda, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5).

Articulating Our Religion

Amajor reason why Hinduism seems difficult to understand is its diversity. Hinduism is not a monolithic tradition. There isn’t a one Hindu opinion on things. And there is no single spiritual authority to define matters for the faith. There are several different denominations, the four largest being Vaishnavism, Saivism, Shaktism and Smartism. Further, there are thousands of schools of thought, or sampradayas, expressed in tens of thousands of guru lineages, or paramparas. Each parampara is typically independent and self-contained in its authority. In a very real sense, this grand tradition can be defined and understood as ten thousand faiths gathered in harmony under a single umbrella called Hinduism, or Sanatana Dharma. The tendency to overlook this diversity is the common first step to a faulty perception of the religion. Most spiritual traditions are simpler, more unified and unambiguous.

All too often, despite its antiquity, its profound systems of thought, the beauty of its art and architecture and the grace of its people, Hinduism remains a mystery. Twisted stereotypes abound that would relegate this richly complex, sophisticated and spiritually rewarding tradition to little more than crude caricatures of snake-charmers, cow worshipers and yogis lying on beds of nails.

While Hindus themselves do not hold these coarse stereotypes, they are often aware of just one small corner of the religion—their own village or family lineage—and oblivious to the vastness that lies outside it. Many Hindus from the North, for instance, are only aware of the Northern traditions, such as that of Adi Shankara, and remain unaware of the equally vigorous and more ancient Southern traditions, such as Saiva Siddhanta.

Unfamiliarity with the greater body of Sanatana Dharma may have been unavoidable in earlier centuries, but no longer. Anyone who is sufficiently determined can track down excellent resources on every facet of the faith. It has, after all, possibly the largest body of scriptural literature of any living religion on Earth. Mountains of scriptures exist in dozens of languages; but they are not all packaged conveniently in a single book or cohesive collection. To ferret out the full breadth of Sanatana Dharma, a seeker would need to read and analyze myriad scriptures and ancillary writings of the diverse philosophies of this pluralistic path. These days, few have the time or determination to face such a daunting task.

Fortunately, there is an easier, more natural way to approach the vastness of Hinduism. From the countless living gurus, teachers and pandits who offer clear guidance, most seekers choose a preceptor, study his teachings, embrace the sampradaya he propounds and adopt the precepts and disciplines of his tradition. That is how the faith is followed in actual practice. Holy men and women, counted in the hundreds of thousands, are the ministers, the defenders of the faith and the inspirers of the faithful.

Hinduism’s Unique Value Today

There are good reasons for today’s readers, Hindu and non-Hindu alike, to study and understand the nature of Hinduism. The vast geographical and cultural expanses that separate continents, peoples and religions are becoming increasingly bridged as our world grows closer together. Revolutions in communications, the Internet, business, travel and global migration are making formerly distant peoples neighbors, sometimes reluctantly.

It is crucial, if we are to get along in an increasingly pluralistic world, that Earth’s peoples learn about and appreciate the religions, cultures, viewpoints and concerns of their planetary neighbors. The Sanatana Dharma, with its sublime tolerance and belief in the all-pervasiveness of Divinity, has much to contribute in this regard. Nowhere on Earth have religions lived and thrived in such close and harmonious proximity as in India. For thousands of years India has been a home to followers of virtually every major world religion, the exemplar of tolerance toward all paths. It has offered a refuge to Jews, Zoroastrians, Sufis, Buddhists, Christians and nonbelievers. Today over one hundred million Indians are Muslim, magnanimously accepted by their majority Hindu neighbors. Such religious amity has occurred out of an abiding respect for all genuine religious pursuits. The oft-quoted axiom that conveys this attitude is Ekam sat anekah panthah, “Truth is one, paths are many.”

What can be learned from the Hindu land that has given birth to Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism and has been a generous protector of all other religions? India’s original faith offers a rare look at a peaceful, rational and practical path for making sense of our world, gaining personal spiritual insight and, potentially, grounding our society in a more spiritually rewarding worldview.

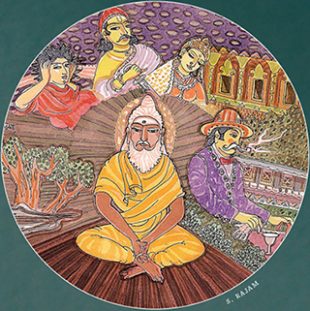

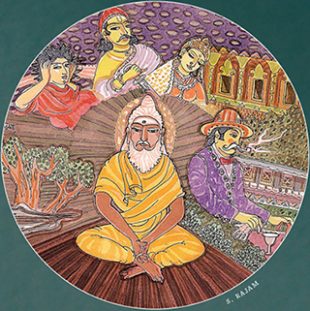

Hinduism boasts teachings and practices reaching back 8,000 years and more, its history dwarfing most other religions. In fact, there is no specific time in history when it began. It is said to have started with time itself. Raimon Panikkar, author of The Vedic Experience, emphasized the relative ages of the major religions, and the antiquity of Hinduism, by reducing them to proportionate human years. With each 100 years of history representing one year of human life, Sikhism, the youngest faith, is five years old. Islam, the only teenager, is fourteen. Christianity just turned twenty. Buddhism, Taoism, Jainism and Confucianism are twenty-five. Zoroastrianism is twenty-six. Shintoism is in its late twenties. Judaism is a mature thirty-seven. Hinduism, whose birthday remains unknown, is at least eighty years old—the white-bearded grandfather of living spirituality on this planet.

The followers of this extraordinary tradition often refer to it as Sanatana Dharma, the “Eternal Faith” or “Eternal Way of Conduct.” Rejoicing in adding on to itself the contributions of every one of its millions of adherents down through the ages, it brings to the world an extraordinarily rich cultural heritage that embraces religion, society, economy, literature, art and architecture. Unsurprisingly, it is seen by its followers as not merely another religious tradition, but as a way of life and the quintessential foundation of human culture and spirituality. It is, to Hindus, the most accurate possible description of the way things are—eternal truths and natural principles inherent in the universe, that form the basis of culture and prosperity. Understanding this venerable religion enables one to fathom the source and essence of human religiosity—to marvel at the oldest example of the Eternal Path that is reflected in all faiths.

While 960 million Hindus live in India, forming 80 percent of the population, tens of millions reside across the globe. These include followers from nearly every nationality, race and ethnic group in the world. The US alone is home to three million Hindus, roughly two-thirds of Indian, Sri Lankan or other South Asian descent and one-third of other backgrounds.

Hindu Scriptures

All major religions are based upon a specific set of teachings encoded in sacred scripture. Christianity has the Bible, for example, and Islam has the Koran. Hinduism proudly embraces an incredibly rich collection of scripture; in fact the largest body of sacred texts known to man. The holiest and most revered are the Vedasand Agamas, two massive compendia of shruti (that which is “heard”), revealed by God to illumined sages centuries and millennia ago. It is said the Vedas are general and the Agamas specific, as the Agamas speak directly to the details of worship, the yogas, mantra, tantra, temple building and such. The most widely known part of the Vedas are the Upanishads, which form the more general philosophical foundations of the faith.

The array of secondary scripture, known as smriti (that which is “remembered”), is equally vast. The most prominent and widely celebrated smriti are the Itihasas (epic dramas and history—specifically the Ramayanaand Mahabharata) and the Puranas (sacred history and mythology). The ever-popular Bhagavad Gita is a small portion of the Mahabharata. The Vedic arts and sciences, including ayurveda, astrology, music, dance, architecture, statecraft, domestic duty and law, are reflected in an assembly of texts known as Vedangas and Upavedas. Moreover, through the ages God-Realized souls, sharing their experience, have poured forth volume upon volume that reveal the wonders of yoga and offer passionate hymns of devotion and illumination. The creation of Hindu scripture continues to this day, as contemporary masters reiterate the timeless truths to guide souls on the path to Divinity.

A clear sign that a person is a Hindu is that he embraces Hindu scripture as his guide and solace through life. While the Vedas are accepted by all denominations, each lineage defines which other scriptures are regarded as central and authoritative for its followers. Further, each devotee freely chooses and follows one or more favorite scriptures within his tradition, be it a selection of Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Tirumantiram or the writings of his own guru. This free-flowing, diversified approach to scripture is unique to the Hindu faith. Scripture here, however, has a different place than in many other faiths. It guides one’s practice, which leads to the goal: personal experience of the Divine. For genuine spiritual progress to take place, the wisdom of scripture must not be merely studied and preached, but lived and experienced as one’s own.

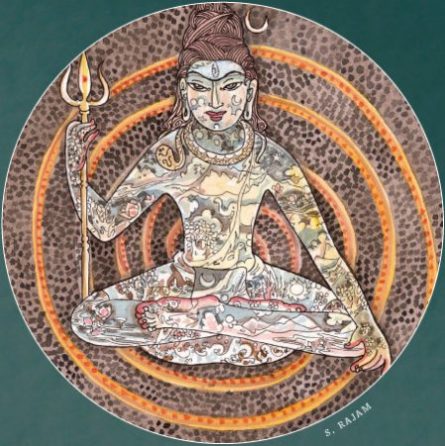

The Nature of God

What is the nature of God in Hinduism is a question that defies a facile answer, for in the Hindu family of faiths each has its own perspective on the Supreme Being, and its own Deity or Deities. For this reason, Hinduism may, to an outsider, appear polytheistic—a term avidly employed as a criticism of choice, as if the idea of many Gods were primitive and false. For the Hindu the many Gods in no way impair the principle of the oneness of Reality. Further complexity and confusion have been introduced with the diaspora, that phenomenon of recent history that has, for the first time, spread Hindus throughout the globe. Outside their native soil, groups of mixed Hindu backgrounds have tended to bring the Deities of all traditions together under one roof in order to create a place of worship acceptable, and affordable, to all. This is something that does not happen in India. This all-Gods-under-one-roof phenomenon is confusing, even to many Hindus, and it tends to lend credence to the polytheistic indictment. Nevertheless, ask any Hindu, and he will tell you that he worships the One Supreme Being, just as do Christians, Jews, Muslims and those of nearly all major faiths. The Hindu will also tell you that, indeed, there is only one Supreme God. If he is a Saivite, he calls that God Siva. If a Shakta Hindu, he will adore Devi, the Goddess, as the ultimate Divinity. If a Vaishnava Hindu, he will revere Vishnu. If he is a Smarta Hindu, he will worship as supreme one chosen from a specific pantheon of Gods. Thus, contrary to prevailing misconceptions, Hindus all worship a one Supreme Being, though by different names. This is because the diverse peoples of India, with different languages and cultures, have, through the longest existing religious history, understood the one God in their own distinct ways. Analogously, India is the only nation with fourteen official languages on its paper currency. All those names don’t change the value of the note!

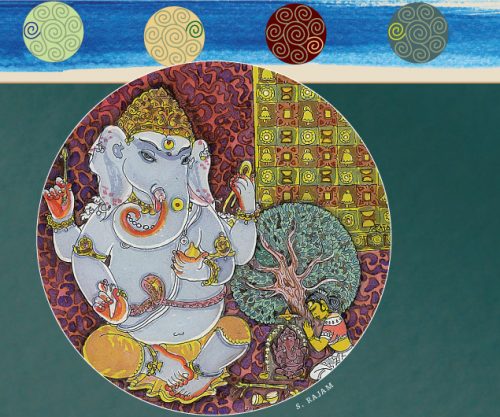

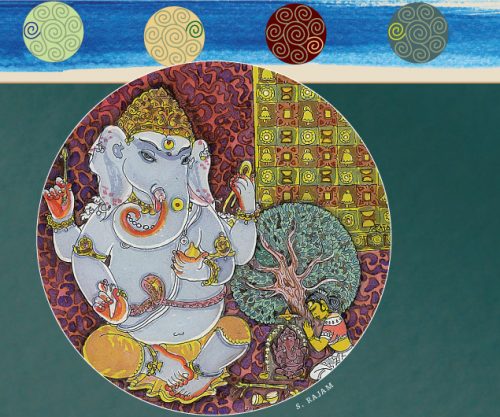

A crucial point that is often overlooked is that having one Supreme God does not repudiate the existence of lesser Divinities. Just as Christianity acknowledges great spiritual beings who dwell near God, such as the cherubim and seraphim, who have both human and animal features, so Hindus revere Mahadevas, or “great angels,” who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. Each denomination worships the Supreme God and its own pantheon of divine beings. The elephant-faced Lord Ganesha is among the most popular, and is perhaps the only Deity worshiped by Hindus of all denominations. Other Deities include Gods and Goddesses of strength, yoga, learning, art, music, wealth and culture. There are also minor Divinities, village Gods and Goddesses, who are invoked for protection, health and such mundane matters as a fruitful harvest. Though these lesser Divinities are called Gods, they are not confused with God, the Supreme.

Each denomination identifies its primary Deity as synonymous with Brahman, the One Supreme Reality exalted in the lofty Upanishads. There, in the cream of Hinduism’s revealed scripture, the matter is crystal clear. God is unimaginably transcendent yet ubiquitously immanent in all things. He is Creator and He is the creation. He is not a remote God who rules from above, as in Abrahamic faiths, but an intimate Lord who abides within all as the essence of everything. There is no corner of creation in which God is not present. He is farther away than the farthest star and closer than our breath. Hinduism calls God “the Life of life.” If His presence were to be removed from any one thing, that thing would cease to exist.

Reincarnation Precept Number Two

Reincarnation, punarjanma, is the natural process of birth, death and rebirth. At death we drop off the physical body and continue evolving in the inner worlds in our subtle bodies, until we again enter into birth. Through the ages, reincarnation has been the great consoling element within Hinduism, eliminating the fear of death. We are not the body in which we live but the immortal soul which inhabits many bodies in its evolutionary journey through samsara. After death, we continue to exist in unseen worlds, enjoying or suffering the harvest of our earthly deeds until it comes time for yet another physical birth. The actions set in motion in previous lives form the tendencies and conditions of the next. Reincarnation ceases when karma is resolved, God is realized and moksha, liberation, is attained; the soul then continues its evolution in more refined, non-physical worlds. The Vedas state, “After death, the soul goes to the next world, bearing in mind the subtle impressions of its deeds, and after reaping their harvest returns again to this world of action. Thus, he who has desires continues subject to rebirth” (Yajur Veda, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.6).

If terms be required, we could characterize this family of faiths as both monotheistic and henotheistic. Hindus were never polytheistic in the sense of believing in many equal Gods. Henotheism (literally, “one God”) better defines the Hindu view. It means the worship of one Supreme God without denying the existence of other Gods. Another set of philosophical terms describe God’s relationship to the universe: panentheism, pantheism and theism. Hindus believe that God is an all-pervasive reality that animates the universe. We can see Him in the life shining out of the eyes of humans and all creatures. This view of God as existing in and giving life to all things is called panentheism. It differs from the similar-sounding view, pantheism, in which God is the natural universe and nothing more, immanent but not transcendent. It also differs from traditional theism, in which God is above the world, apart and transcendent but not immanent. Panentheism is an all-encompassing concept. It says that God is both in the world and beyond it, both immanent and transcendent. That is the highest Hindu view.

Unlike purely monotheistic religions, Hinduism tends to be tolerant and welcoming of religious diversity, embracing a multiplicity of paths, not asking for conformity to just one. So, it’s impossible to say all Hindus believe this or that. Some Hindus give credence only to the formless Absolute Reality as God; others accept God as personal Lord and Creator. Some venerate God as male, others as female, while still others hold that God is not limited by gender, which is an aspect of physical bodies. This freedom, we could say, makes for the richest understanding and perception of God in all of Earth’s existing faiths. Hindus accept all genuine spiritual paths—from pure monism, which concludes that “God alone exists,” to theistic dualism, which asks, “When shall I know His Grace?” Each soul is free to find his own way, whether by devotion, austerity, meditation, yoga or selfless service.

The Nature of Self

The driving imperative to know oneself—to answer the questions “Who am I?” “Where did I come from?” and “Where am I going?”—has been the core of all great religions and schools of philosophy throughout human history. Hindu teachings on the nature of self are as philosophically profound as they are pragmatic. We are more than our physical body, our mind, emotions and intellect, with which we so intimately identify every moment of our life, but which are temporary, imperfect and limiting. Our true self is our immortal soul, or atma, the eternal, perfect and unlimited inner essence, unseen by the human eye—undetectable by any of the human senses, which are its tools for living in this physical world.

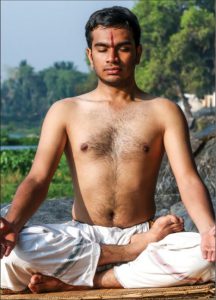

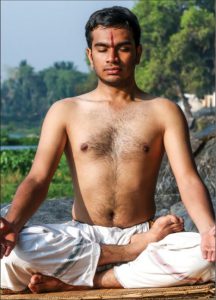

The Vedas teach that the Divine resides in all beings. Our true, spiritual essence is, like God, eternal, blissful, good, wise and beautiful by nature. The joining of Brahman, or God, and the atman, or soul, is known as yoga, a Sanskrit word that shares the same root as the English word yoke. We spend so much of our time pursuing beauty, knowledge and bliss in the world, not knowing that these objects of our desire are already within us as attributes of our own soul. If we turn our focus within through worship and meditation, identifying with our true spiritual self, we can discover an infinite inner treasure that easily rivals the greatest wealth of this world.

Personal spiritual development is enhanced through understanding the closely related processes of karma and reincarnation. The individual soul undergoes repeated cycles of birth, death and rebirth. This is known as the wheel of samsara. During each earthly manifestation, an individual’s karma (literally “work” or “actions”) determines his future psycho-physical state. Every ethically good act results, sooner or later, in happiness and spiritual development; whereas ethically wrong actions end in loss and sorrow. Thus, the principle of karma is an idea that celebrates freedom, since at every moment we are free to create our future states of existence through our present actions and states of consciousness. This philosophical worldview encourages followers of Hinduism to live happily, morally, consciously and humbly, following the Eternal Way.

Hinduism is a mystical religion, leading the devotee to personally experience the Truth within, finally reaching the pinnacle of consciousness where the realization is attained that man and God are one. As divine souls, we are evolving into union with God through the process of reincarnation. We are immortal souls living and growing in the great school of earthly experience in which we have lived many lives. Knowing this gives followers a great security, eliminating the fear and dread of death. The Hindu does not take death to be the end of existence, as does the atheist. Nor does he, like Western religionists, look upon life as a singular opportunity, to be followed by eternal heavenly existence for those souls who do well, and by unending hell for those who do not. Death for the Hindu is merely a moment of transition from this world to the next, simultaneously an end and a new beginning. The actions and reactions we set in motion in our last life form our tendencies in the next.

Despite the heartening glory of our true nature spoken of in scripture, most souls are unaware of their spiritual self. This ignorance or “veiling grace” is seen in Hinduism as God’s purposeful limiting of awareness, which allows us to evolve. It is this narrowing of our awareness, coupled with a sense of individualized ego, that allows us to look upon the world and our part in it from a practical, human point of view. Without the world, known as maya, the soul could not evolve through experience. The ultimate goal of life, in the Hindu view, is called moksha, liberation from rebirth. This comes when earthly karma has been resolved, dharma has been well performed and God is fully realized. All souls are destined to achieve the highest states of enlightenment, perfect spiritual maturity and liberation, but not necessarily in this life. Hindus understand this and do not delude themselves that this life is the last. While seeking and attaining profound realizations, they know there is much to be done in fulfilling life’s other three goals: dharma, righteousness; artha, wealth; and kama, pleasure.

All-Pervasive Divinity Precept Number Three

As a family of faiths, Hinduism upholds a wide array of perspectives on the Divine, yet all worship the one, all-pervasive Supreme Being hailed in the Upanishads. As Absolute Reality, God is unmanifest, unchanging and transcendent, the Self God, timeless, formless and spaceless. As Pure Consciousness, God is the manifest primal substance, pure love and light flowing through all form, existing everywhere in time and space as infinite intelligence and power. As Primal Soul, God is our personal Lord, source of all three worlds, our Father-Mother God who protects, nurtures and guides us. We beseech God’s grace in our lives while also knowing that He/She is the essence of our soul, the life of our life. Each denomination also venerates its own pantheon of Divinities, Mahadevas, or “great angels,” known as Gods, who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. The Vedas proclaim, “He is the God of forms infinite in whose glory all things are—smaller than the smallest atom, and yet the Creator of all, ever living in the mystery of His creation. In the vision of this God of love there is everlasting peace. He is the Lord of all who, hidden in the heart of things, watches over the world of time” (Krishna Yajur Veda, Shvetashvatara Upanishad 4.14-15).

In some Hindu traditions, the destiny of the soul after liberation is perceived as eternal and blissful enjoyment of God’s presence in the heavenly realms, a form of salvation given by God through grace, similar to most Abrahamic faiths. In others, the soul’s destiny is perfect union in God, a state of undifferentiated oneness likened to a river returning to its source, the sea, and becoming one with it—either immediately upon death, or following further evolution of the soul in the inner worlds. For still others, the ultimate state has no relationship with a Godhead, but is understood as undifferentiated oneness without form or being, a return or merger in the infinite All, somewhat akin to the Buddhist’s nirvana.

Hinduism in Practice

Hinduism’s three pillars are temple worship, scripture and the guru-disciple tradition, around which all spiritual disciplines revolve. These include prayer, meditation and ritual worship in the home and temple, study of scripture, recitation of mantras, pilgrimage to holy places, austerity, selfless service, generous giving, the various yogas, and following good conduct. Festivals and singing of holy hymns are dynamic activities.

Hindu temples, whether they be small village sanctuaries or toering citadels, are esteemed as God’s consecrated abode. In the temple, Hindus draw close to the Divine and find a refuge from the world. God’s grace, permeating everywhere, is most easily known within these holy precincts. It is in this purified milieu that the three worlds—physical, astral and causal—commune most perfectly, that devotees can establish harmony with inner-plane spiritual beings. Traditional temples are specially sanctified, possessing a ray of spiritual energy connecting them to the celestial worlds.

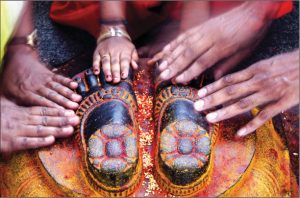

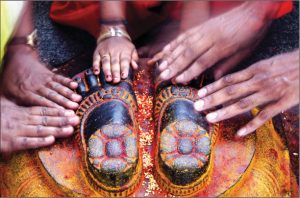

Temple rituals, performed by Hindu priests, take the form of puja, a ceremony in which the ringing of bells, passing of flames, presenting of offerings and intoning of chants invoke the devas and Gods, who then come to bless and help the devotees. Personal worship during puja may be an expression of festive celebration of important events in life, of adoration and thanksgiving, penance and confession, prayerful supplication and requests, or contemplation and the deepest levels of superconsciousness. The stone or metal Deity images enshrined in the temple are not mere symbols of the Gods; they are the form through which their love, power and blessings flood forth into this world. Devout Hindus adore the image as the Deity’s physical body, knowing that the God or Goddess is actually present and conscious in it during puja, aware of devotee’s thoughts and feelings and even sensing the priest’s gentle touch on the metal or stone.

Hindus consider it most important to live near a temple, as it is the center of spiritual life. It is here, in God’s home, that the devotee nurtures his relationship with the Divine. Not wanting to stay away too long, he visits weekly and strives to attend each major festival, and to pilgrimage to a far-off temple annually for special blessings and a break from his daily concerns.

For the Hindu, the underlying emphasis of life is on making spiritual progress, while also pursuing one’s family and professional duties and goals. He is conscious that life is a precious, fleeting opportunity to advance, to bring about inner transformation, and he strives to remain ever conscious of this fact. For him work is worship, and his faith relates to every department of life.

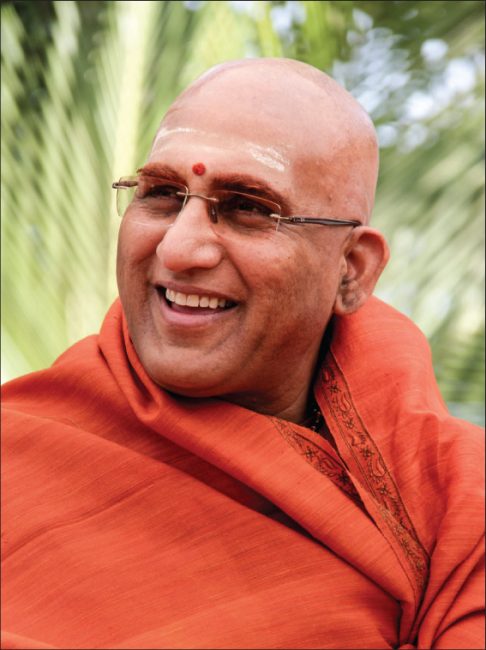

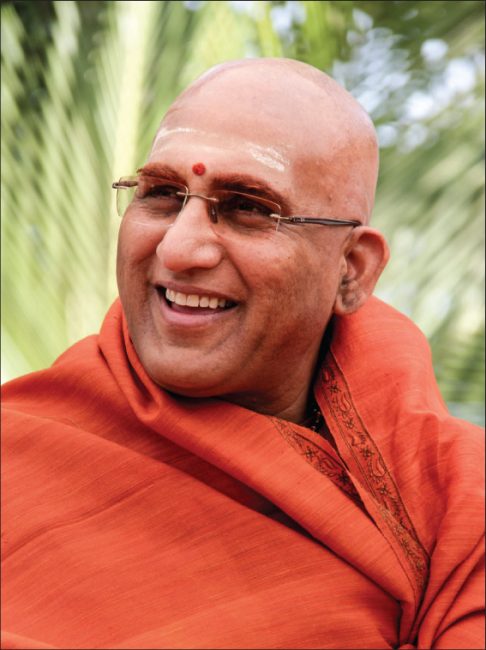

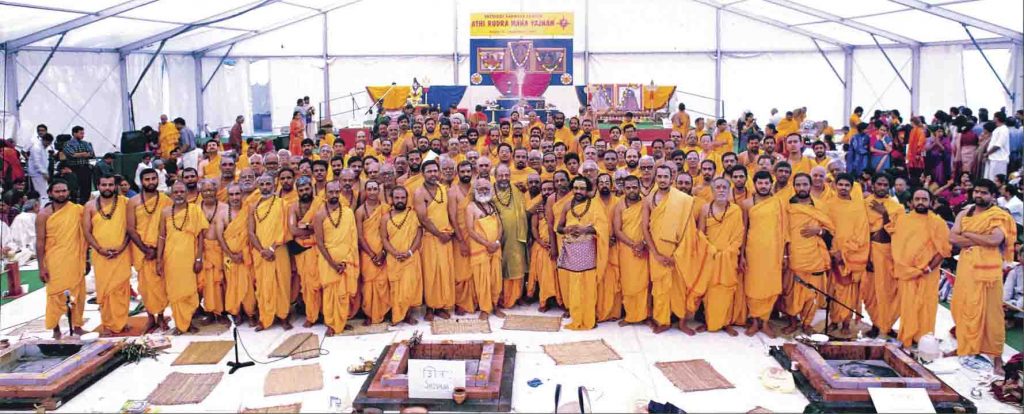

Hinduism’s spiritual core is its holy men and women—millions of sadhus, yogis, swamis, vairagis, saints and satgurus who have dedicated their lives to full-time service, devotion and God Realization, and to proclaiming the eternal truths of Sanatana Dharma.

In day-to-day life, perhaps no facet of dharma is as crucial as the spiritual teacher, or satguru. These holy men and women are a living spiritual force for the faithful. They are the inspirers and interpreters, the personal guides who, knowing God themselves, can bring devotees into God consciousness. In all Hindu communities there are gurus who personally look after the spiritual practices and progress of devotees. Such preceptors are equally revered whether they are men or women. In few other religions are women allowed to occupy the highest seats of reverence and respect.

Within the Hindu way is a deeply rooted desire to lead a productive, ethical life. Among the many virtues instilled in followers are truthfulness, fidelity, contentment and avoidance of greed, lust and anger. A cornerstone of dharma is ahimsa, noninjury toward all beings. Vedic rishis who revealed dharma proclaimed ahimsa as the way to achieve harmony with our environment, peace between people and compassion within ourselves. Devout followers tend to be vegetarians and seek to protect the environment. Selfless service, seva, to God and humanity is widely pursued as a way of softening the ego and drawing close to the Divine. Charity, dana, is expressed through myriad philanthropic activities.

Hindus wear sectarian marks, called tilaka, on their foreheads as sacred symbols, distinctive insignia of their heritage. They prefer cremation of the body upon death, rather than burial, knowing that the soul lives on and will inhabit a new body on Earth.

Dharma Precept Number Four

When God created the universe, He endowed it with order, with the laws to govern creation. Dharma is God’s divine law prevailing on every level of existence, from the sustaining cosmic order to religious and moral laws which bind us in harmony with that order. In relation to the soul, dharma is the mode of conduct most conducive to spiritual advancement, the right and righteous path. It is piety and ethical practice, duty and obligation. When we follow dharma, we are in conformity with the Truth that inheres and instructs the universe, and we naturally abide in closeness to God. Adharma is opposition to divine law. Dharma is to the individual what its normal development is to a seed—the orderly fulfillment of an inherent nature and destiny. The Tirukural (verses 31–32) reminds us, “Dharma yields Heaven’s honor and Earth’s wealth. What is there then that is more fruitful for a man? There is nothing more rewarding than dharma, nor anything more ruinous than its neglect.”

Perhaps one of this faith’s most refreshing characteristics is that it encourages free and open thought. Scriptures and gurus encourage followers to inquire and investigate into the nature of Truth, to explore worshipful, inner and meditative regimens to directly experience the Divine. This openness is at the root of Hinduism’s famed tolerance of other cultures, religions and points of view, capsulated in the adage, Ekam sat viprah bahuda vadanti, meaning “Truth is one, the wise describe it in different ways.” The Hindu is free to choose his path, his way of approaching the Divine, and he can change it in the course of his lifetime. There is no heresy or apostasy in Hinduism. This, coupled with Hinduism’s natural inclusiveness, gives little room for fanaticism, fundamentalism or closed-mindedness anywhere within the framework of Hinduism. It has been aptly called a threshold, not an enclosure.

There is a false concept, commonly found in academic texts, that Hinduism is world-negating. This depiction was foisted upon the world by 19th-century Western missionary Orientalists traveling in India for the first time and reporting back about its starkest and strangest aspects, not unlike what Western journalists tend to do today. The wild-looking, world-renouncing yogis, taking refuge in caves, denying the senses and thus the world, were of sensational interest, and their world-abandonment became, through the scholars’ eyes, characteristic of the entire religion. While Sanatana Dharma proudly upholds such severe ways of life for the few, it is very much a family-oriented faith. The vast majority of followers are engaged in family life, firmly grounded in responsibilities in the world. Hinduism’s essential, time-tested monastic tradition makes it no more world-negating than Christianity or Buddhism, which likewise have traditions of renunciate men and women living apart from the world in spiritual pursuits. Young Hindu adults are encouraged to marry; marriages are encouraged to yield an abundance of children; children are guided to live in virtue, fulfill duty and contribute to the community. The emphasis is not on self-fulfillment and freedom but on the welfare of the community, as expressed in the phrase, Bahujan hitaya, bahujan sukhaya, meaning “the welfare of the many and the happiness of the many.”

Definitions from Prominent Hindus

In this magazine and in our books we have offered this dictionary-style definition of our faith: India’s indigenous religious and cultural system, followed today by nearly one billion adherents, mostly in India, but with large populations in many other countries. Also called Sanatana Dharma, “eternal religion” and Vaidika Dharma, “religion of the Vedas.” Hinduism is the world’s most ancient religion and encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. It is a family of myriad faiths with four primary denominations: Saivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism. These four hold such divergent beliefs that each is a complete and independent religion. Yet they share a vast heritage of culture and belief—karma, dharma, reincarnation, all-pervasive Divinity, temple worship, sacraments, manifold Deities, the guru-shishya tradition and a reliance on the Vedas as scriptural authority. Great minds have tackled the thorny challenge of defining Sanatana Dharma, and we would like to share a few of their efforts here.

Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, renowned philosopher and president of India from 1962 to 1967, states in The Hindu View of Life: “The Hindu recognizes one Supreme Spirit, though different names are given to it. God is in the world, though not as the world. He does not merely intervene to create life or consciousness, but is working continuously. There is no dualism of the natural and the supernatural. Evil, error and ugliness are not ultimate. No view is so utterly erroneous, no man is so absolutely evil as to deserve complete castigation. There is no Hell, for that means there is a place where God is not, and there are sins which exceed His love. The law of karma tells us that the individual life is not a term, but a series. Heaven and Hell are higher and lower stages in one continuous movement. Every type has its own nature which should be followed. We should do our duty in that state of life to which we happen to be called. Hinduism affirms that the theological expressions of religious experience are bound to be varied, accepts all forms of belief and guides each along his path to the common goal. These are some of the central principles of Hinduism. If Hinduism lives today, it is due to them.”

Bal Ghangadhar Tilak, scholar, mathematician, philosopher and Indian nationalist, named “the father of the Indian Revolution” by Jawaharlal Nehru, summarized Hindu beliefs in his Gitarahasya. This oft-quoted statement, so compelling concise, is considered authoritative by Bharat’s courts of law: “Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence; recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are diverse; and realization of the truth that the number of Gods to be worshiped is large, that indeed is the distinguishing feature of the Hindu religion.”

Sri K. Navaratnam, esteemed Sri Lankan religious scholar, enumerated a more extensive set of basic beliefs in his book, Studies in Hinduism, reflecting the Southern Saiva Agamic tradition. 1) A belief in the existence of God. 2) A belief in the existence of a soul separate from the body. 3) A belief in the existence of the finitizing principle known as avidya or mala. 4) A belief in the principle of matter—prakriti or maya. 5) A belief in the theory of karma and reincarnation. 6) A belief in the indispensable guidance of a guru to guide the spiritual aspirant towards God Realization. 7) A belief in moksha, or liberation, as the goal of human existence. 8) A belief in the indispensable necessity of temple worship in religious life. 9) A belief in graded forms of religious practices, both internal and external, until one realizes God. 10) A belief in ahimsa [nonviolence] as the greatest dharma or virtue. 11) A belief in mental and physical purity as indispensable factors for spiritual progress.

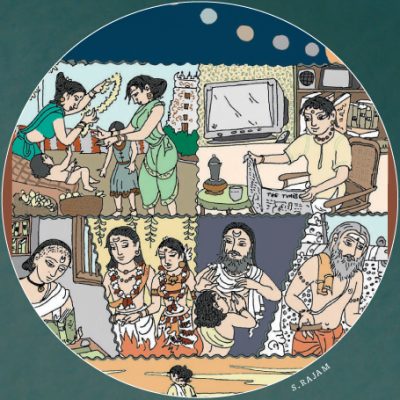

Five Practices

Here are the minimal practices (also known as pancha nitya karmas) to nurture future citizens who are strong, responsible, tolerant and traditional.

1. Worship, Upasana: The dear children are taught daily worship in the family shrine room—rituals, disciplines, chants, yogas and religious study. They learn to be secure through devotion in home and temple, wearing traditional dress, bringing forth love of the Divine and preparing the mind for serene meditation.

2. Holy Days, Utsava: The dear children are taught to participate in Hindu festivals and holy days in the home and temple. They learn to be happy through sweet communion with God at such auspicious celebrations. Utsava includes fasting and attending the temple on Monday or Friday and other holy days.

3. Virtuous Living, Dharma: The dear children are taught to live a life of duty and good conduct. They learn to be selfless by thinking of others first, being respectful of parents, elders and swamis, following divine law, especially ahimsa, mental, emotional and physical noninjury to all beings. Thus they resolve karmas.

4. Pilgrimage, Tirthayatra: The dear children are taught the value of pilgrimage and are taken at least once a year for darshan of holy persons, temples and places, near or far. They learn to be detached by setting aside worldly affairs and making God, Gods and gurus life’s singular focus during these journeys.

5. Rites of Passage, Samskara: The dear children are taught to observe the many sacraments which mark and sanctify their passages through life. They learn to be traditional by celebrating the rites of birth, name-giving, head-shaving, first feeding, ear-piercing, first learning, coming of age, marriage and death.

Mahatma Mohandas K. Gandhi: “I call myself a Sanatani Hindu because I believe in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas and all that goes by the name of Hindu scriptures, and therefore in avatars and rebirth. In a concrete manner he is a Hindu who believes in God, immortality of the soul, transmigration, the law of karma and moksha, and who tries to practice truth and ahimsa in daily life, and therefore practices cow protection in its widest sense and understands and tries to act according to the law of varnashrama.”

Sri Pramukh Swami Maharaj of the Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Sanstha (Swaminarayan Faith) propounds: 1) Parabrahman, one, supreme, all-powerful God: He is the Creator, has a divine form, is immanent, transcendent and the giver of moksha. 2) Avataravada, manifestation of God on Earth: God Himself incarnates on Earth in various forms to revive dharma and grant liberation. 3) Karmavada, law of action: the soul reaps fruits, good or bad, according to its past and present actions, which are experienced either in this life or future lives. 4) Punarjanma, reincarnation: the mortal soul is continuously born and reborn in one of the 8,400,000 species until it attains liberation. 5) Moksha, ultimate liberation: the goal of human life. It is the liberation of the soul from the cycle of births and deaths to remain eternally in the service of God. 6) Guru-shishya sambandha, master-disciple relationship: guidance and grace of a spiritually perfect master, revered as the embodiment of God, is essential for an aspirant seeking liberation. 7) Dharma, that which sustains the universe: an all-encompassing term representing divine law, law of being, path of righteousness, religion, duty, responsibility, virtue, justice, goodness and truth. 8) Vedapramana, scriptural authority of the Vedas: all Hindu faiths are based on the teachings of the Vedas. 9) Murti-puja, sacred image worship: consecrated images represent the presence of God which is worshiped. The sacred image is a medium to help devotees offer their devotion to God.

Sri Swami Vivekananda, speaking in America, proclaimed: “All Vedantists believe in God. Vedantists also believe the Vedas to be the revealed word of God—an expression of the knowledge of God—and as God is eternal, so are the Vedas eternal. Another common ground of belief is that of creation in cycles, that the whole of creation appears and disappears. They postulate the existence of a material, which they call akasha, which is something like the ether of the scientists, and a power which they call prana.”

Sri Jayendra Saraswati, 69th Shankaracharya of the Kamakoti Peetham, Kanchipuram, defined in his writings the basic features of Hinduism as follows. 1) The concept of idol worship and the worship of God in His nirguna as well as saguna form. 2) The wearing of sacred marks on the forehead. 3) Belief in the theory of past and future births in accordance with the theory of karma. 4) Cremation of ordinary men and burial of great men.

The Vishva Hindu Parishad declared its definition in a Memorandum of Association, Rules and Regulations in 1966: “Hindu means a person believing in, following or respecting the eternal values of life, ethical and spiritual, which have sprung up in Bharatkhand [India] and includes any person calling himself a Hindu.”

The Indian Supreme Court, in 1966, formalized a judicial definition of Hindu beliefs to legally distinguish Hindu denominations from other religions in India. This list was affirmed by the Court as recently as 1995 in judging cases regarding religious identity. “1) Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence as the highest authority in religious and philosophic matters and acceptance with reverence of Vedas by Hindu thinkers and philosophers as the sole foundation of Hindu philosophy. 2) Spirit of tolerance and willingness to understand and appreciate the opponent’s point of view based on the realization that truth is many-sided. 3) Acceptance of great world rhythm—vast periods of creation, maintenance and dissolution follow each other in endless succession—by all six systems of Hindu philosophy. 4) Acceptance by all systems of Hindu philosophy of the belief in rebirth and pre-existence. 5) Recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are many. 6) Realization of the truth that numbers of Gods to be worshiped may be large, yet there being Hindus who do not believe in the worshiping of idols. 7) Unlike other religions, or religious creeds, Hindu religion’s not being tied down to any definite set of philosophic concepts, as such.”

Nine Beliefs of Hinduism

1 Hindus believe in the divinity of the Vedas, the world’s most ancient scripture, and venerate the Agamas as equally revealed. These primordial hymns are God’s word and the bedrock of Sanatana Dharma, the eternal religion which has neither beginning nor end.

2 Hindus believe in a one, all-pervasive Supreme Being who is both immanent and transcendent, both Creator and Unmanifest Reality.

3 Hindus believe that the universe undergoes endless cycles of creation, preservation and dissolution.

4 Hindus believe in karma, the law of cause and effect by which each individual creates his own destiny by his thoughts, words and deeds.

5 Hindus believe that the soul reincarnates, evolving through many births until all karmas have been resolved, and moksha, spiritual knowledge and liberation from the cycle of rebirth, is attained. Not a single soul will be eternally deprived of this destiny.

6 Hindus believe that divine beings exist in unseen worlds and that temple worship, rituals, sacraments as well as personal devotionals create a communion with these devas and Gods.

7 Hindus believe that a spiritually awakened master, or satguru, is essential to know the Transcendent Absolute, as are personal discipline, good conduct, purification, pilgrimage, self-inquiry and meditation.

8 Hindus believe that all life is sacred, to be loved and revered, and therefore practice ahimsa, “noninjury.”

9 Hindus believe that no particular religion teaches the only way to salvation above all others, but that all genuine religious paths are facets of God’s Pure Love and Light, deserving tolerance and understanding.