Since 2004, the International Folk Art Market in New Mexico, USA, has hosted more than 1,000 creators from 100 countries in the world’s largest exhibition and sale of folk crafts. Artists’ earnings have exceeded US$34 million and impacted more than a million lives in the communities they represent. Join us on a stroll to visit Indian, Nepalese and other master artists, some of whom can support dozens of families for a whole year from this long weekend’s sales.

By Claire Burkert, New Mexico

Photos by Thomas Kelly

It’s a day of joy and anticipation: over 150 artisans from sixty countries are arriving on Museum Hill to set up their booths for the annual Santa Fe International Folk Art Market. Many have never been to the Market or even to the US. What does it look like to them, this assembly of large tents erected under New Mexico state’s big open sky, amid the rolling hills which are still infused with the spirit of the native peoples whose home this was? I toured last year’s Market to report for Hinduism Today—and of course couldn’t resist shopping for my own apparel and home decor.

The tents of the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market are set up in early July amidst cultural museums built in an adobe style distinctive to New Mexico. Seeing the plain adobe walls, two Mithila artists from Nepal ask: “Shouldn’t we paint some Gods and elephants on them?” Nepal and India are well represented at this respected market—mostly in the realm of textiles—due to their plethora of ancient crafts. Their booths sit side by side with dozens of other countries resulting in a dizzying array of styles. Enthusiasts can browse a wide variety of traditional and modern art which could take months to discover by visiting the countries themselves.

At home, most artisans struggle in the face of modern, cheap manufacturing, while at this market they are elevated and supported by well-to-do clientele and volunteers eager to help preserve the handmade. Additional prestigious markets in other countries could go a long way in boosting folk art’s profile and sales. This particular market is also a rare opportunity to meet fellow artisans from around the world. While mingling to discover each other’s history and talents, they find that folk art everywhere faces the same challenges of financial stability and seeking to remain environmentally friendly.

As the artisans arrive at their booths in the tents to unpack, one senses that what has taken place is something just short of a miracle. After being selected half a year earlier from a pool of 400 applicants, the artisans needed not only to make and pack their products but also to obtain passports, visas and air tickets and arrange shipping. Great credit goes to IFAM’s director and staff who coordinate logistics, including dealing with last-minute emergencies: denied visas, delayed flights and shipments held up in customs. Assisting the IFAM staff is a dedicated team of 1,300 volunteers who help to welcome artisans, translate, put up and take down tents, deliver food, and much more. A huge IFAM community comes together to make this extraordinary and impactful event happen.

I serve on the IFAM’s Selection Committee, which carefully reviews artisans’ applications. The question often arises, “Is this folk art?” Over time our definition of folk art has evolved, allowing fresh variations of cultural traditions and welcoming innovation. In recent applications, I’ve noticed that more and more artisans and designers are expressing deep concerns about the sustainability of artisan communities and about the global environment. These concerns affect the materials they use and types of products they make. About 13 percent of artisans accepted to last year’s Market were from India and Nepal.

Meeta Mastani

I first entered the booth of Meeta Mastani, a fabric artist working with fourth-generation printers and dyers in Rajasthan for thirty years. I learned about her company, Bindaas, when I saw my colleague Tony wearing a shirt block-printed all over with images of cameras. “That’s folk art?” I asked, but then I learned more about the challenges faced by this ancient tradition, and the significance of the designer-artisan partnership to the future of the craft. “Women transfer the designs onto wood, and the men carve them out,” Meeta explains, “but because block printing has increasingly been replaced by screen printing, traditional block makers are suffering.”

Every part of the block printing process is by hand and is natural: the wood blocks, the dyes, the pastes. The process requires experience and skill. The many natural ingredients include limestone, indigo, pomegranate rind, alum, catechu, tree gums, leftover husk of wheat eaten by bugs, edible oil, waste iron, tamarind seed powder, myrobalan, ferrous sulfate, riverine clay and alizarin. Of concern is the great deal of water required by the natural dyeing and printing process. As water is growing dangerously scarce, the artisan community has initiated a rainwater recharge project and built a water tank that can store up to 100,000 liters of water.

Although the block-printing tradition faces threats, “Bindaas” means carefree and daring, a feeling reflected in the motifs of the shirts, saris and towels here at the Market. “For a colonized country which has supplied the world with printed fabric for thousands of years, it is very important to use our own designs,” explains Meeta. Developed in tandem with the block printers, the motifs are inspired by “the many light and playful moments in the lives around us.” They include chess pieces, sandals, sunglasses, tiffin boxes, movie cameras, kites, bicycles, ice creams, footprints, scooters, motorcycles, tea cups and handbags.

The Market is the only place Bindaas sells retail. “It is special here and they look after us well,” says Meeta. “I’ve learned here that people are the same everywhere.” I observe a buyer chuckling over a t-shirt block printed with images of the pressure cooker found in every Indian kitchen.“I like play,” she says, “and they look at my stuff and smile. That makes me happy.”

For many hundreds of years, Indian craftspeople have practiced natural dyeing, use of natural fibers and recycling. Over the next days, I want to catch up with more of the Indian participants and learn how they are adapting to a changing world. In a threatened climate, what steps towards sustainability must artisan communities take?

Hemangini Rathore

Sudarshan means beautiful, and this is the name of a company run by Hemangini Rathore whom I spotted in the adjacent booth. She, like Meeta, has a long relationship with artisans in Rajasthan. “From a young age I learned about craft by working in village workshops,” she recounts. “My parents wanted me to go to business school, but instead I studied textiles in Mumbai.”

Hemangini works with several traditional printing processes to “revive, sustain and innovate folk textile crafts and empower artisans.” Her booth is packed with women shopping for her kaftans, scarves, jackets and capes that employ various traditional block printing and dyeing techniques, including Dabu printing, a unique process that was revived after Indian independence. The block is printed in mud paste, which resists dye. When the fabric is dyed and then washed to remove the mud, the unique undyed pattern is revealed. This process can be repeated to make rich looking double and triple Dabu effects. Hemangini also works with traditions of Sanganer—prints of delicate floral patterns that were created in Moghul times. In recent products she has introduced Shibori, the Japanese tradition of resist dyeing through stitching.

“I learned practical skills in the villages and bumped up design and finishing. The important thing in contemporary design is not to take away,” she explains. “And you have to be in the field. As in cooking a recipe, you can’t sit in NYC and wave a magic wand. You need years of working on the ground to develop a relationship with the artisan community.”

“Even during Covid we didn’t stop,” she adds. “We developed new products, we developed colors. And now we’ve put our block printing work out in the open air, since we can’t work inside. We are back to the traditional way—Corona brought us outdoors, and block printing is, in fact, meant to be seen in natural light. Indoors with AC, you don’t get the color right. Sun and breeze play with the dyes.”

Hemangini relates her practice of craft to her Hindu belief: “The organic aspect of Hinduism is to not overindulge and to focus on our work. I also believe in karma. I believe I’ve done well because I’ve given back to the community. When you pay the artisans regularly, they are blessing you. Preserving crafts automatically helps everyone. I do whatever I can do to share my knowledge and to sell and to create sustainability.”

Thilak Reddy

Wandering onward, I encountered Thilak Reddy who is both a traditional Kalamkari textile artist and innovator. Kalamkari is an ancient traditional fabric art using a kalam or pen, a bamboo stick with a padding of cloth above its point that helps the artist regulate the flow of ink as he draws. In the past, large naturally colored Kalamkari scrolls were displayed in temples. Expanding on traditional depictions of the tree of life or scenes from the Ramayana or Mahabharata, Thilak has developed a range of designs expressive of earth, water, sky, flora and fauna. His team of 20 women, for whom practicing this craft is not traditional, are equal partners in his company, Kalam Shastra. “We have never changed the process—we use the same tools and materials. It is the designs that are different. We wanted to make it more into art.”

He shows us charcoal that he uses for drawing the initial outline, alum as mordant, various pens and brushes, myrobalan for fixative, alizarin for yellow color, madder and modhuga flower (flame of the forest) for reds and oranges, and cake indigo for blue.

“I love it here in Santa Fe,” he exclaims. “Here you are treated as an artist. If you want to do something out of the box, you don’t want to be constrained about whether it sells or not. The Market encourages me to be free. For instance, we’ve always made dupatta (shawls) but here people make them into caftans, pillows and table cloths. The Market’s imagination is wide.”

Men and women alike are trying on his naturally colored shawls, captivated by the variety of designs. Each cloth has rhythm: bold poppies reach tall and seem to bend in a breeze, a river winds between shorelines seen from above, lotus flowers float in bubbly blue water, white deer sit below graceful oak leaves. Thilak attaches the phrase “Exist loudly” to a photo of one of the pieces that he posts on Instagram. As an artist in cooperation with a team of talented women, he has developed each work so that it has a soul and identity of its own.

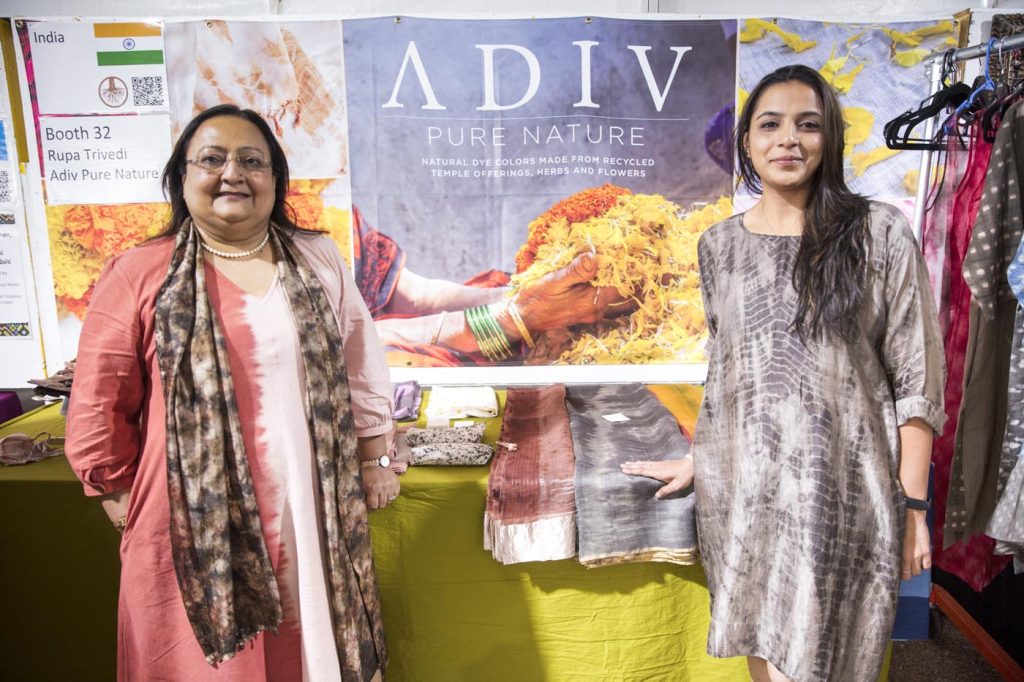

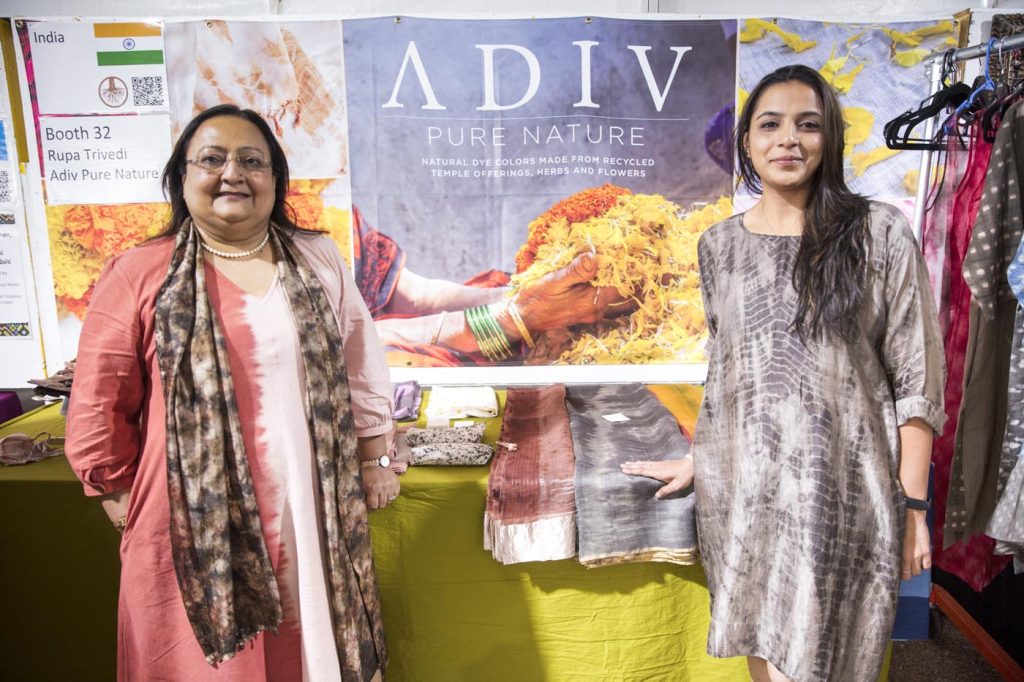

Rupa Trivedi

My meandering brought me to Rupa Trivedi, founder of Adiv, an urban artisanal enterprise in Mumbai. Her story is unique: “I was worshiping at the Shree Siddhivinayak Ganapati Temple in Mumbai when I saw how flower offerings were collected afterwards in bins and dumped into the sea, choking the nearby waterways.”

Rupa realized she could help lessen organic sea pollution if she could utilize these spiritual materials as dyes, linking to a long folk tradition of natural dyeing. Now, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday she collects marigold, hibiscus and pieces of coconut from the temple, and once a week she collects roses and lilies from the Peer Haji Ali Dargah Mosque. Additionally, she collects onion skins and coconut from food vendors.

Rupa began this work with two pots in a kitchen. She has applied her background in engineering to creating systems for processing this organic waste. The flowers are brought to her studio, where artisans separate the petals and dry them in the shade before grinding them into powder. “Mumbai has a moist climate, so it is important to be able to store dyes through the monsoon season,” she explains. Additionally, some flowers are used fresh to create bright yellows. Rupa has taught her team how to measure the dyestuffs and to make larger batches of dyes in order to be able to make multiple matching garments.

She employs twelve dyers and ten tailors and pattern cutters to create her fabrics. Her daughter Priti, an Indian beauty-pageant finalist who shares her mother’s vision, has joined Rupa in Santa Fe. “We use one day a week for creativity,” says Rupa, as Priti shows me a shirt pattern invented by a dyer who wrapped the fabric around a pipe before dyeing it. In another garment, the sewing team had decided to combine segments of silk and a cotton fabric, each fabric dyed with the same flowers but absorbing the dye differently.

Rupa sees her work in Adiv as a way to return to the values she had as a child participating in rituals in the rural village of Ganeshpuri. She hopes to bring the natural world and Indian dye traditions to young urbanites, and believes that the blessings of the flowers will continue to flow into the world. Here in Santa Fe this is certainly the case: “We have the chance to meet so many people here,” she comments, as Priti helps a customer who is admiring a garment with an impressionistic pattern of flowers created by marigold petals.

Hetal Shrivastav

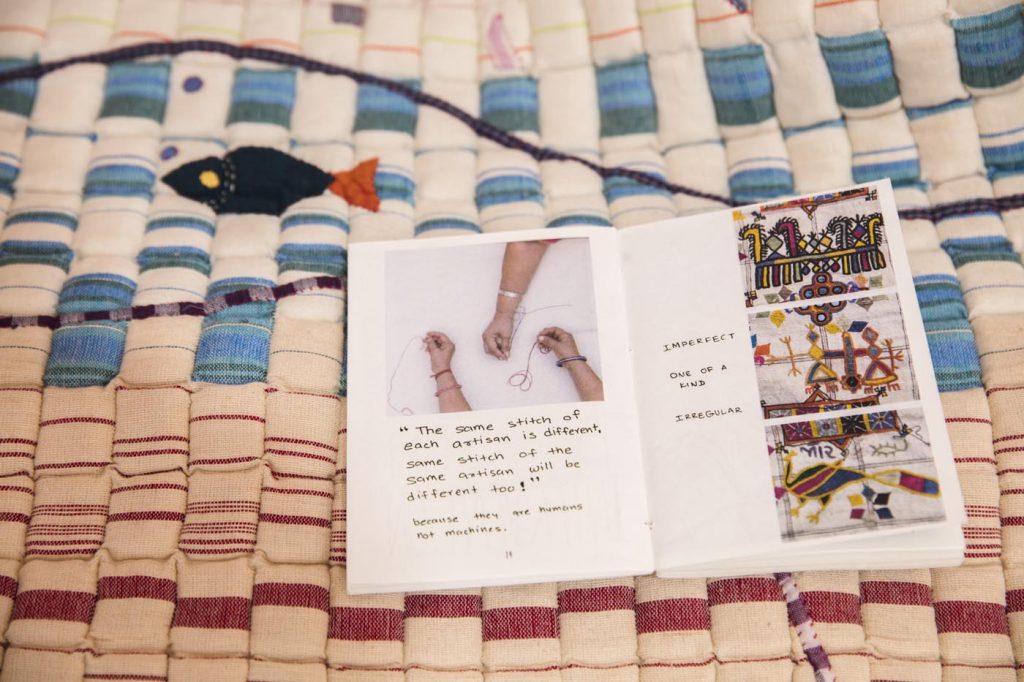

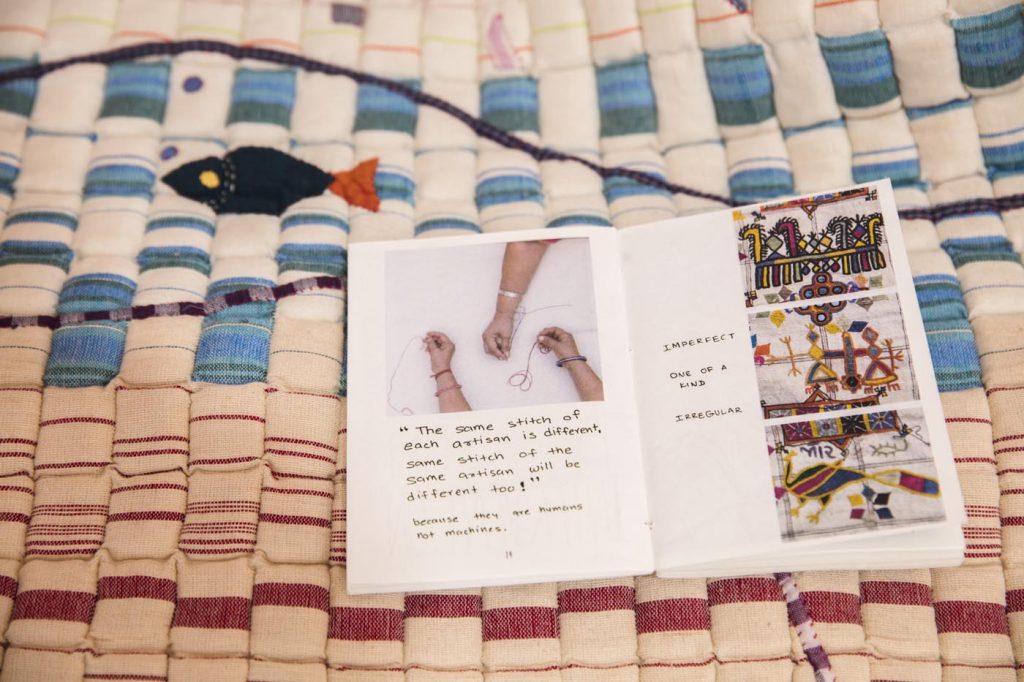

Raasleela is an organization in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, led by a young designer, Hetal Shrivastav whom I came across next. The small manual she has written about Raasleela’s mission explains she had entered the fashion industry but something felt wrong. She stepped back “to explore, slowly, how to bring a difference to artisans’ lives and to improve conditions of the planet.” She describes Raasleela as a happy family, where employees have flexible working hours and can work at home. In this happiness amongst the artisans, she says, “I find my purpose.”

Indeed, some of the most unusual Raasleela products literally speak of purpose: one garment is embroidered with a postage stamp and a message from the artisan directly to the customer: “Dear Reader, I hope you and your family is doing well. I am Sumi from Gujarat, India. I live with my aunt and cousins. I am a surface designer. I love nature. I pray to God every day I will one day speak English fluently.” Striking are hand-stitched quilts with colorful abstract shapes on either side. The artisans use discarded materials—called “upcycled”—as well as cloth that is unbleached, because, as Hetal writes in her manual, “Why should marine life be disturbed just to look good? Textile chemicals are the second most water-polluting industry!”

Buyers linger in the booth, taking time to understand both the verbal and visual expressions that artisans have created on each garment or quilt. No two are alike. Individuality is the point: “The same stitch of each artisan is different. The same stitch of the same artisan will be different, too—because they are humans, not machines,” writes Hetal in her manual. “We celebrate imperfections and reject nothing!”

Asif Sheikh

After Hetal I met Asif Sheikh. His embroidered products follow a similar dedication to the handmade, but strive for technical perfection. Asif defines himself as an artist who researches and revives embroidery. “Embroidery is God’s gift to me and it is my responsibility to share this gift with artisans and to teach them this quality. Mine is the best in the world.”

“My goal is not to earn money but to earn knowledge,” he says. “With my knowledge of craft, the work must go up and not down.” He shows us the neatly finished back of an embroidered shawl (one can scarcely discern the back from the front) and the perfect 90-degree corners of the shawl. “In my studio we never talk about time, we talk about quality,” he adds. Each piece is 100% handmade, without the use of machines. “You cannot copy craft with technology,” he warns, believing crafts using machines do not deserve to be called craft at all. “Even our labels are hand-embroidered—they are never polyester.”

“You have to speak when you make the craft, so I have done this with a confluence of birds for my theme this year,” he says, displaying a spectacularly beautiful silk shawl with birds embroidered in fine indigo chain stitch. “Indigo from Ahmedabad was exported all over. It is a sacred color—my work is a sacred job. Last year I was missing the lavender that grows in Santa Fe,” he says, showing me another collection of shawls embroidered with lavender sprigs. “I had come here since 2010 and I would always spend 10-15 days in Santa Fe to get creative energy. This city has given me so much. During Covid, I designed a lavender motif with natural indigo. I used handspun khadi (cotton) with wild silk for the lavender. When I am talking about nature, I only want to use natural materials.”

Asif works with fifteen artisans in his studio and 200 from all over India. He has founded the Craft Design Society (CDS), a school that teaches design and weaving to artisans’ children. The free three-year course covers 22 processes of weaving. “I started embroidery at the age of seven, then did interior design,” says Asif. “I gained recognition in the world, and believe I should give this recognition to others who are deserving.” Next year he hopes to bring CDS weavers to the Market so that a younger generation of weavers can benefit from the experience, just as he has.

Siju Swamji and Siju Dinesh Vishram

We were not surprised to learn that Asif buys base cloth for his products from Siju Swamji Vishram and his brother Siju Dinesh Vishram, whose booth is just across the way. Renowned in Gujarat, these weavers have woven with natural fibers and dyes for generations. (Raasleela also sources unbleached cloth from these brothers.) Siju Swamji is showing a customer one of his bedcovers, a product he developed after four previous trips to the Market. Before, he had only made shawls and scarves. Inspiration for new products, he tells us, comes from looking around the Market. His brother Siju Dinesh Vishram shows me images on his phone of motifs of a Guatamalan weaver’s supplementary weft that impressed him. “Here I’ve made Mexican friends, Hungarian friends, friends from Uzbekistan and Kyrgistan. Yesterday I met a woman artisan from Pakistan.”

Siju adds, “The Market brings fine people who know art and craft and don’t bargain. Sales are so good that with the income we can support ourselves and 65 families for a whole year.”

Pachan Premjibhai Siju

Nearby the Vishrams booth is that of Pachan Premjibhai Siju, coming from 12 generations of weavers who wove wool and cotton textiles for local communities in Kutch, Gujarat. “I learned weaving from my father and two brothers,” he writes in his brochure for his business, Three Threads. “When we faced a financial crisis, I worked at a mining company. But my health suffered in the factory environment, and so I returned to weaving.”

Sadly, he was unable to obtain a visa to attend the Market. But his message to his clients is carried through his weaving. One set of motifs depicts the industries that came to Kutch with smokestacks, emitting pollution. Another shows a near-treeless dry landscape. Happier motifs include children planting trees and a watering can. “I have been thinking about climate change since I studied at SKV (Somaiya Kala Vidya, a design school for artisans in Kutch). “I created my own new extra weft motifs to portray my ideas, and so my scarves show a different story on either end.”

He has also introduced lighter natural materials preferred by his clients: finer cotton, mill-spun bamboo, hand-spun lotus fibers, tussar and eri silk. Learning he also got new ideas after a WhatsApp collaboration with a group of Oaxacan weavers, I wandered over to a Oaxacan booth to see their products.

From Mexico, Peru & Finland

“It’s like a dream to see all these things from different countries,” says Aurelia Gomez Jimenez, returning to chat with me after a tour through some of the tents. Aurelia comes from a village in Santa Maria Tlahuitoltepec in the mountains near Oaxaca, where the traditions of weaving rebozo had died out. Rebozos are woven textiles used by Mexican women in many communities to shelter their heads from sun, to wrap their torso or to carry babies and bundles. Aurelia’s husband Bonaficio began learning to weave rebozos on a backstrap loom when he was eight years old. Taught the whole process of preparing the loom and weaving by his grandmother, he has revived the practice of weaving rebozos in their community and introduced a pedal loom. Today, Aurelia dyes yarns while her daughter and grandmother do the special knotting of the fringe.

These shawls in their earth colors, with long, delicate, complex fringes, hang on the wall of the Jimenezs’ booth in rich testimony to their ancestors’ tradition. Their dyes are luminous, making one think of the magic hour of early evening when everything is cast in warm hues. For their dyes they use the bark of oakwood and eagle trees, two local types of marigold that produce olive green and mustard yellow, juice from a plantain stem, as well as purchased indigo and cochineal.

They employ several community members (single mothers and adults with disabilities) in both weaving and making the fringes for the shawls. Weaving is Aurelia and Bonifacio’s full-time work. It has helped them to have a better house and provide an education for their daughter. They are also gratified they can contribute to the community by employing marginalized people in their workshop.

One of the world’s grand masters of weaving is Nilda Callanaupa Alvarez, who has presented Peruvian textiles at the Market 16 times. “The Market gives an opportunity for us to show our work,” says Nilda, “and it is also for building relationships with clientele. We have the chance to form intercultural relationships—it is ultimately about the artist, not only the product. With many of the artisans we are like brothers and sisters. I have friends now from Laos, Indonesia, Mexico, India…now I want to create a conference in Peru inspired by the Market and bring people there.”

As a young girl tending her family’s sheep, Nilda learned spinning and weaving. She saw that the weaving tradition in Cuzco was disappearing, so she started gathering weavers in the courtyard of her parents’ home. “I started as a weaver and helped to start a nonprofit, because it is satisfying to help so many weavers to have an income,” Nilda explains. The Centro de Textiles Traditionales del Cusco (CTTC) was established in 1996. “I work with 500 weavers in ten co-ops. Every product tag shows the name of the weaver.” At the Market she has learned how to set up, tell her story, interact with a client and learn what he or she likes, essential knowledge for working on the scale of the CTTC. The impact and the scope of her work are tremendous.

“The motifs in our textiles are inspired from our Andean environment and include water represented in various ways, leaves, flowers, branches, flora, animals and constellations. You’ll also find motifs from pre-Colombian textiles of Peru,” she explains. Yarn is made with a drop spindle, colors of her weavings are all natural, the material wood and alpaca, the quality impeccable. The bedcovers, bags and shawls of wool and alpaca, in their rainbow stripes of deep shades of natural colors, speak of rich Andean nature and culture.

Selling under the same tent at the Market, but usually a world away, is the Finnish textile artist Hannele Kongas. Like Nilda, she weaves with the time-honored natural colors and is repeating traditions of her ancestors—including the Sami people of northern Norway, whose techniques she uses, and, far back, the Vikings. On the wall of her booth she hangs a large photo of the home in the stark Lapland landscape where she was born. “Finnish nature is not just a source of inspiration to me,” she says. “The need to protect its fragile ecosystem guides every step of my working process.”

She describes the materials and processes: “I’m a wool enthusiast; the Finnish Kainuu Grey sheep is endangered, and there are only 1,000 ewes left. It’s important to me that the sheep farm is organic and that they take good care of their sheep.” Hannele continues, “Using rainwater whenever possible and adding adhesive to the dyebath at the same time with dyeing, I try to save water and electricity. Cultivated dyestuffs such as madder, woad, weld, cochineal and sometimes turmeric, onion scales, nettle and tansy form the basic colors for my weaves.” Below the photo of her childhood home, her scarves are hung by clothespins, just as they might have been as she grew up. The colors and soft textures evoke nature in the Finnish countryside. When I pass the booth later on, they are nearly sold out.

Anuradha Kuli

It is all to easy to get distracted, while heading in one direction at the Market, as you encounter artisans and crafts new to you. From my unplanned visits to Mexico, Peru and Finland I return once again to the Indian subcontinent to meet Anuradha Kuli and delight in her naturally dyed textiles from Assam.

Like Nilda and Hannele, Anuradha is deeply rooted in her culture. Each Assamese household still has a loom, and even a woman who is a university graduate will wish to weave a Muga mekhela-chadar, a local type of sari, for her wedding day. Muga silk is a golden-hued wild silk unique to Assam. In the past, the golden Muga textiles, with their smooth, glossy texture, were reserved for high officials and royalty.

Graceful and soft-spoken, Anuradha is an authority on natural dyes and sericulture. In addition to Muga silk, she uses eri silk (a white silk that can be processed without killing the silkworm) tussar silk (silk made by silkworms in a wild forest) and mulberry silk. She uses a range of natural dyes—lac and iron to make purple, turmeric, pomegranate and much else. Her natural silk saris are purchased for celebrity weddings across India and featured in India Fashion Week. It impresses me that her saris have been embraced by the urban fashion world, while the processes of making them and the motifs are so rooted in natural and rural life. She shows me motifs of an aquatic plant, a bird couple below a tree who wish to meet, a scarecrow that will chase birds away, and wheels of a bullock cart.

Coming to the Market for the first time, Anuradha feels odd to be unknown, since her brand, “Naturally Anuradha,” is famous in India’s urban centers. But it seems clear that after spending time in her booth, the American clientele will fully appreciate the integrity of her extraordinary textiles.

Women Weave

When it’s time to make visits to two more Indian scarf makers, I realize the Market will be open only a few more hours—and I am behind on making purchases! My first stop is WomenWeave, a charitable trust dedicated to helping female weavers earn income for their families. The scarves, in silk and cotton, have a rich range of colors. It is so hard to choose that I finally select three rather than one, happy to know that my purchases will help support the women and their families. Women in the weaving tradition are often behind the scenes, helping their husbands who are the main weavers. In this project, women are given training opportunities that help them build their skills and become recognized for their creative products.

Adil Mustak & Zakiya Katri

Next I visit the booth of Bandhani weavers Adil Mustak Khatri and his wife Zakiya. Bandhani is a tie-and-dye technique in which tiny knots are tied with cotton thread along a stenciled pattern. Where the cloth is tied, the dye cannot reach. The couple also employ another dyeing technique, in which the fabric is folded and a wooden shape is clamped to each side of the fabric to make a pattern. A third technique, Shibori, involves stitching that resists the dye. With these dyeing techniques they have created their most recent collection inspired by Islamic patterns and architecture. “Now I think anything can be done in bandhani,” comments Adil. I choose a cotton scarf, indigo dyed, with the pattern resembling a carved stone jali (screen) typical of Moghul architecture. I plan to give it to an architect friend. Then, wrapped in the soft, flowing cotton in front of the mirror, I decide to buy another for myself.

Puja Bhargava Kamath

In the booth next to the indigo-dyed scarves I see a woman buyer trying on lacquer bangles in a beautiful array of colors. Curious to learn more, I meet Puja Bhargava Kamath, who is the creative force behind a community project in Channapatna, a small town in South India. For 200 years people had been making lacquered wooden toys from the soft-ivory tree, but the market for these toys was dwindling. To help broaden the market for their products, Puja guided 20-30 men and women to make lacquered bracelets and other jewelry.

“This is a sustainable craft that uses only branches of locally grown wood, known for its medicinal properties. The branches regenerate every five years and can be harvested again,” she tells me. “As the wood is shaped into the desired form on the lathe, the friction creates heat. The lacquer stick pressed against it adheres to the heated wooden surface, imparting the color and a glossy sheen. Once the wooden bangles are covered with lac, they are buffed with a leaf of a local screw pine, giving a smooth and lustrous surface.” A graduate of the National Institute of Fashion and Technology (NIFT) in Delhi, Puja explains the importance of collaboration between the designer and the artisans. Together they can create products that are not “museum copies, but something fresh, something current, something clearly and proudly from India.” Convinced, I try on a beautiful olive-hued bracelet and an orange one, and proudly carry them to the cashier.

So far I have spent about $350 dollars on my five scarves in the $40-$100 range and two bangles for $30 apiece. I still plan to run back to Raasleela for a one of a kind upcycled quilt, my biggest purchase at $500. Meanwhile, I bump into my friend Anne who is wearing Asif’s embroidered indigo shawl that I had my eye on—she paid $400 for this shawl, which is a work of art. In her bag she carries a printed jacket from Sudarshan for just $175. The price range at the market is wide, meeting the tastes and interests of different types of buyers and collectors: a gold filigree necklace made by traditional jewelers from Spain may cost over $2,000, while on a fine rug from Uzbekistan I could spend much more. Whatever the price, Anne and I would not be able to mail order these products from Amazon. At the Market we’ve seen the highest quality examples of what skilled artisans and artists can make, yet they are not sold under a luxury brand name. Moreover, we’ve had the opportunity to meet the makers themselves and so have learned about the whole process of making the piece that we’re taking home: these products come with experiences.

Shalini Karn

The Market is closing soon, but we still have more artisans to visit. Amongst these are painters in very different styles. Shalini Karn is an artist in the Madhubani tradition. As a young girl, Shalini watched her mother create these delicate paintings before picking up the brush herself. “I craft my own pictorial language using traditional Mithila technique, expressing my imagination and things I’ve experienced firsthand,” says Shalini. Some of her imagery is deeply personal, such as a depiction of a baby in a mother’s womb. Other paintings comment on women’s traditional roles: she depicts a woman holding a cricket bat and a woman pedaling a cycle rickshaw. An important aspect of Shalini’s identity as a traditional Mithila artist is the act of giving back to other young women. “I have been running workshops for underprivileged young girls,” explains Shalini, adding that she hopes “students from across the country will one day be contributing to this tradition.”

Her paintings have a fresh sense of color and detail. If you examinie closely what looks like a line or small dots, you see how in many of them she has depicted hundreds of tiny ants: “I feel connected in various ways to this tiny but inspiring insect,” she says.

Bhaskar Chitrakar

Bhaskar Chitrakar is a painter following the Kalighat Patachitra tradition. Originally, Kalighat artists made scroll paintings of religious themes. In mid 19th-century Kolkata, the artists started responding to social and political issues, often with a satirical style. Bhaskar begam learning from his father when he was six or seven and by age 13 had completed his training.

“Kalighat painting should make people laugh,” he says. He continues to paint babu-bibi, aristocratic couples of the 19th century, images often patronized by the aristocrats themselves. But Bhaskar has created new paintings in the same finely executed style, as evidenced by a painting of the Statue of Liberty, whom he has dressed in a sari. “When I was little, I dreamed of coming to the US, and this work was a way of realizing my dream.” Now, after 30 years, his dream has come true.

Bhaskar likes to incorporate other styles from around the world. He admires Frida Kahlo and has painted portraits of her. He also likes to incorporate contemporary themes: in one painting Kali uses her third eye to zap a Covid germ, and in another an aristocratic boy is chasing a Covid germ as if it were a ball.

Conclusion

I meet Wendie Cook, executive director of the Citadelle Art Museum in Texas. “The work is so fantastically irreverent,” she exclaims. She has purchased a painting of a man whose head has been pooped on by a pigeon. I am more attracted to a sweeter painting of a man arriving in Santa Fe, standing in awe before one of the characteristic pueblo-style adobe buildings. He wears formal Indian attire and holds a bag with vegetables he has bought at an Indian bazaar. I see this man as the artist himself, arriving from India and entering the world where I find him.

The designers, artisans and artists I’ve met in these few days have inspired me with their commitment to quality, and to this earth. They are shepherding their traditions in a way that is mindful of the changing world we live in. Let them guide us then, and let us fill our lives with their beautiful and conscientiously made creations.

As Siju Swamji listed his new international friends, I reflected on how the Market allows the opportunity for representatives of different nations to come together. The last night of the Market there is a dance party. I am moved to tears, watching the small Guatamalan weaver dancing with the tall jeweler from Niger. The jeweler from Israel dances with the Palestinian glass maker. The interaction between artisans is not about copying and competition. It is about learning, sharing, respecting. It is about connectivity, and how one wishes the world to be.

And now it’s 5pm. Shoppers are leaving with their last purchases. I feel sadness as the booths are disassembled and products packed, either for storage or shipping back home. The artisans board buses to their hotels; soon they will be on planes again. There is a distressing racket as the tents are taken down by a team of strong volunteers. By morning, Museum Hill will look empty.

But during the five days of the Market this year, three million dollars were generated through the visits of 11,000 people. What carries on is incredible financial support for artisan communities, as well as an abundance of valuable experience, friendships and good memories. Artisans are already sending in their applications for 2023. The plans for the next Market are rolling forward, and we are penciling in our calendars for July 5-9, 2023.

Stay Informed

Stay Informed

The next santa fe international Folk Art Market will take place in July 2023. Stay informed by visiting the website: https://folkartmarket.org/. Plan your visit now!

Wish to Volunteer? For 17 years, volunteers have provided their expertise, spirit of friendship, dedication and resourcefulness to make this the largest folk art market of its kind.

Volunteer Program: https://folkart

market.org/volunteer/opportunities/

Questions? Visit the Volunteer FAQ or contact Francesca at: 1-505-992- 7616 or francesca@folkartmarket.org

Wish to Donate? Make a tax-deductible donation to one of several Market funds. You can sponsor a first-time artist, an artist who is uniquely innovating his/her craft tradition, or a returning artist who may need support to cover attendance costs.

https://folkartmarket.org/donate/where-your-passion-meets-ifams-mission/

Wish to Stay Updated? To keep up to date on year-long Market activities and to read about the work of selected artisans from all around the world, sign up for the IFAM newsletter:

https://folkartmarket.org/events-programs/ifam-media/

Author & Photographer

Author Claire Burkert is an American based in Kathmandu. For over 30 years she has worked with artists in Nepal and other countries, with a focus on promoting indigenous traditions of architecture, craft and design.

Thomas Kelly is a renowned photographer who has provided photographs to Hinduism Today for many years. He is also based in Kathmandu, Nepal. See: thomaslkellyphotos.com wild-earth-journeys.com