Meeting the many peoples of Assam

Assam, India’s Northeast state embracing the immense Brahmaputra River valley, is a land of remarkable variety—of people, traditions, religious practice, flora, fauna and natural resources. Join us as we visit the major temples and religious institutions of this place of ancient and modern migrants from both inside and outside modern India.

By Rajiv Malik, New Delhi

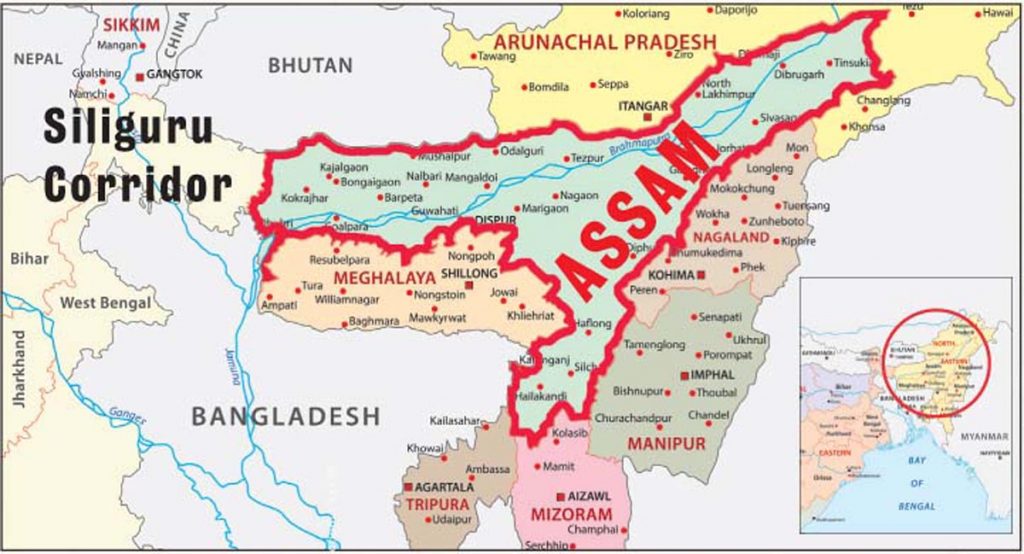

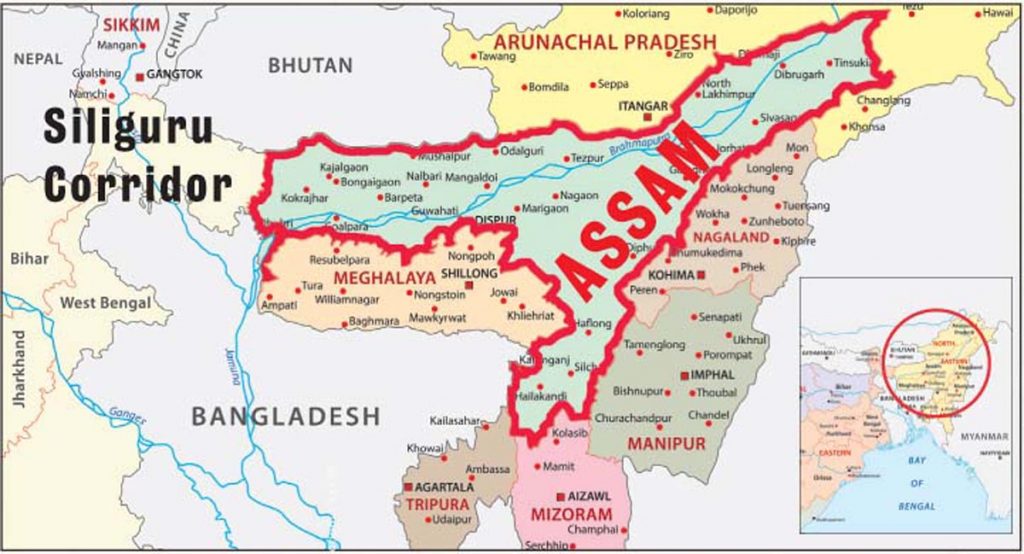

Assam, one of the “seven sisters” states of northeastern India, is famous for its Vaishnava satras (religious centers) and majestic ancient temples, including Kamakhya for the Goddess Shakti and Sivasagar, built by the Ahom dynasty in the 18th century. The name Assam is possibly based on Ahom, though others ascribe it to a-cham (“undefeated”) from the Tai language, ha-sam (“land of the Bodo people”) or asama (“peerless”) from Sanskrit. In ancient times the area was known as Kamarupa. The Pandava brothers of the Mahabharata lived and married here while in exile.

Assam is 61% Hindu, 34% Muslim, 3.7% Christian plus a small number of Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs. It is home to all the three main streams of Hinduism: Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Saivism—this among a population of 31 million people comprising hundreds of tribal, ethnic, linguistic and religious communities speaking 45 languages. Of the 20 largest tribes, the most prominent are the Bodos and Misings of Tibeto-Burmese origin. There are also millions of Bangladeshi illegal migrants, both Hindu and Muslim. Assam is blessed with an abundance of natural resources, including tea, silk, oil and the mighty Brahmaputra River.

Hinduism Today assigned me and photographer Thomas Kelly the challenging job of profiling Hinduism in Assam in just nine days. Assam is a complex topic to report on, so we have divided our report into two parts. The first, in this issue, covers the capital, Guwahati, and the regions around it; the second, in the July/August/September 2017 issue, will cover Dibrugarh, the tea country and Majuli island.

Kamakhya Temple

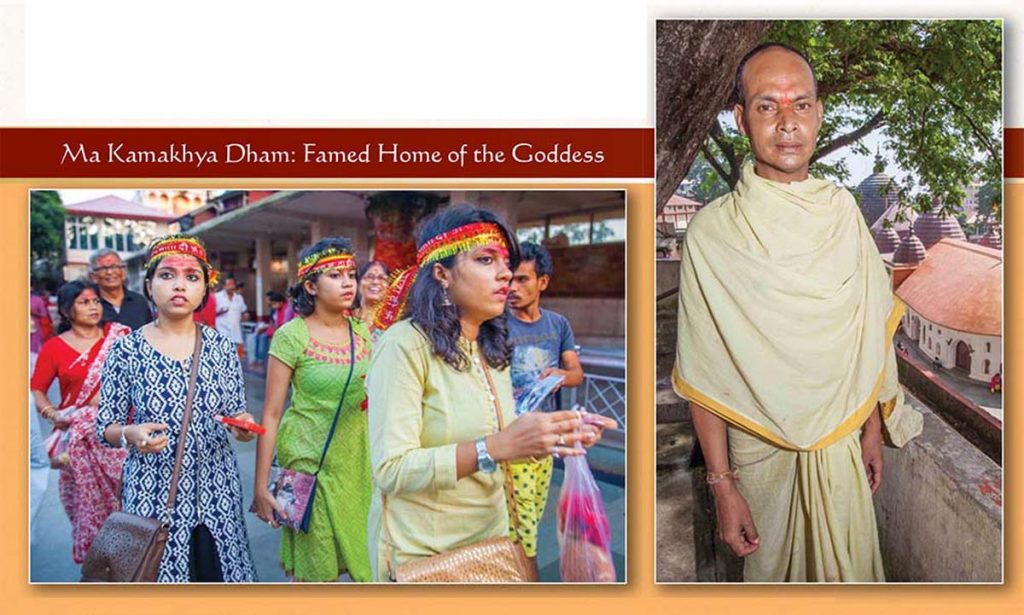

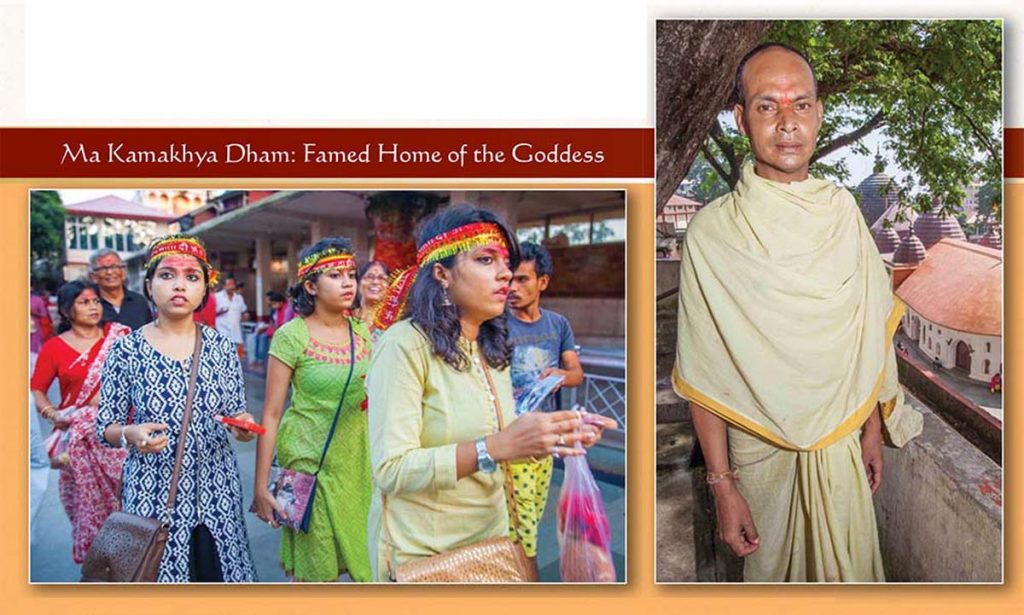

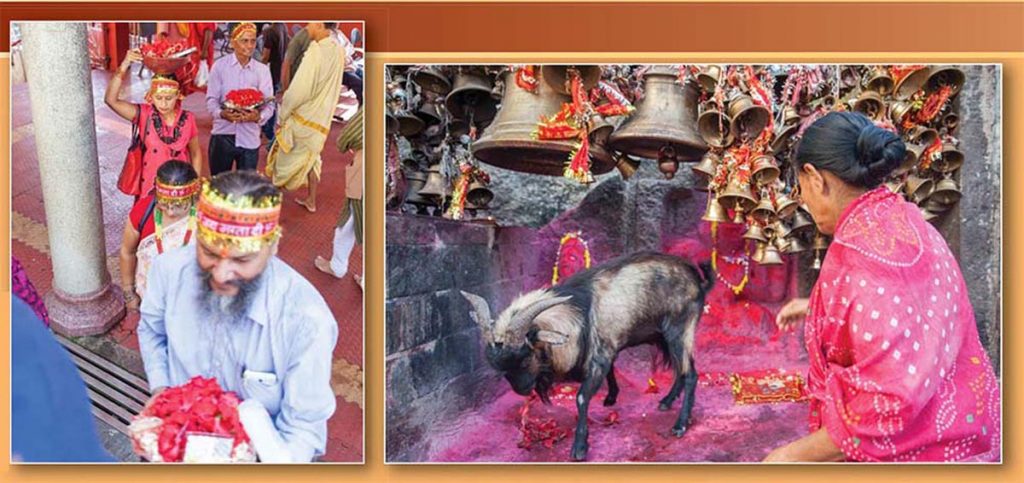

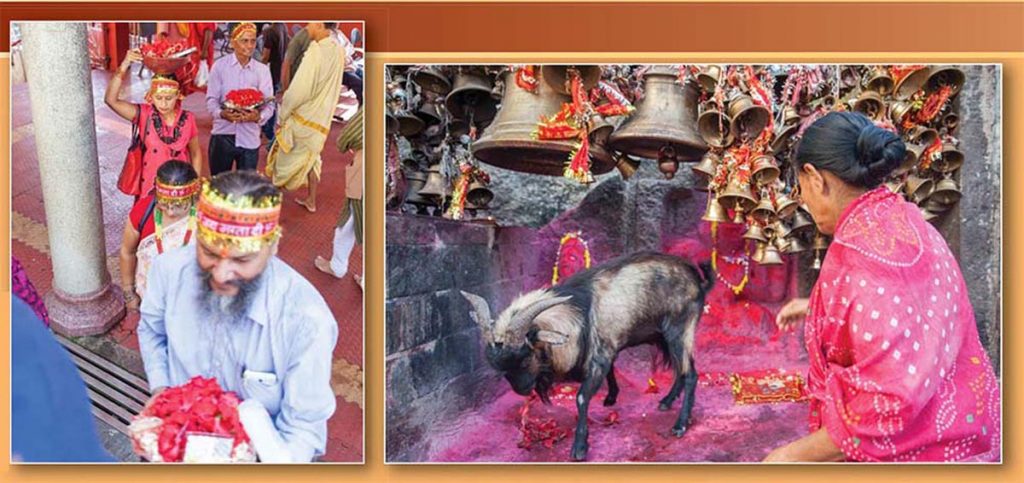

The most famous temple of Assam is that of Ma Kamakhya, situated on the Nilachal Hill in a western part of Guwahati. It is an age-old seat of tantric culture and one of the oldest of the 51 Shakti Peeths, centers for the Goddess. There are many legends associated with the origin and building of the temple. It attracts two million devotees and a large number of tantrics during an annual festival celebrated here known as Ambubachi Mela.

Though there were no special activities the day we visited with our guide, Nitai Das of Ekal Vidyalaya schools, the place was overflowing with pilgrims. Security was tight, and at first we were unable to get any special consideration as journalists. Fortunately, the temple administrator appeared unexpectedly—or by divine intervention, listened to our plea and requested a priest, Viraj Sharma, to show us around. Viraj’s grandfather was a popular priest, but Viraj has an outside job and serves at the temple part time out of devotion to the Goddess. The temple’s 300 priestly families have various hereditary duties, as assigned by the kings many generations back, according to Bhupati Kant Sharma Badpujari, one of the priests who conducts puja.

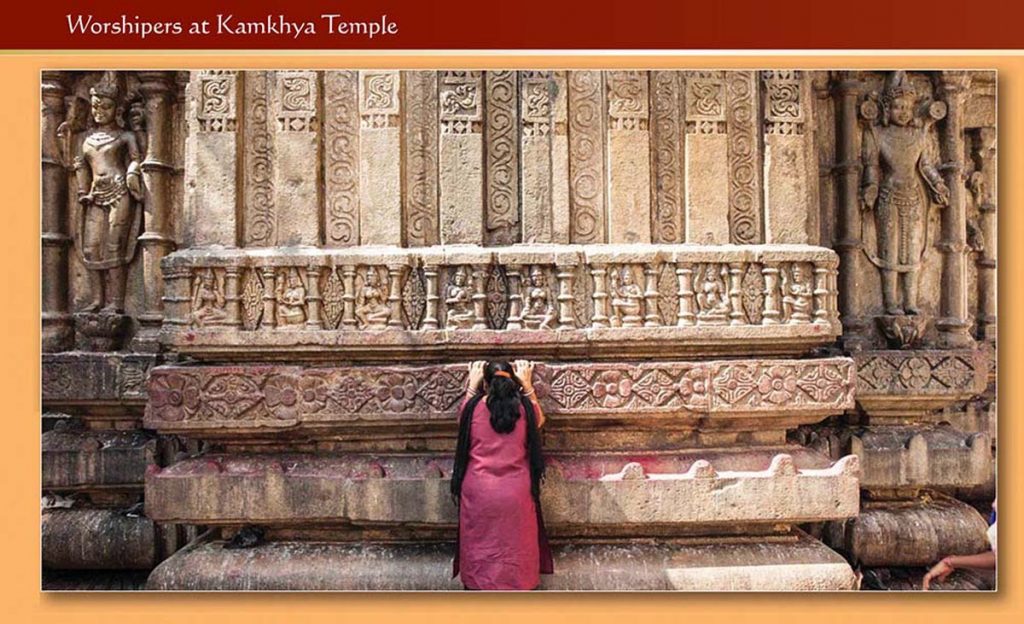

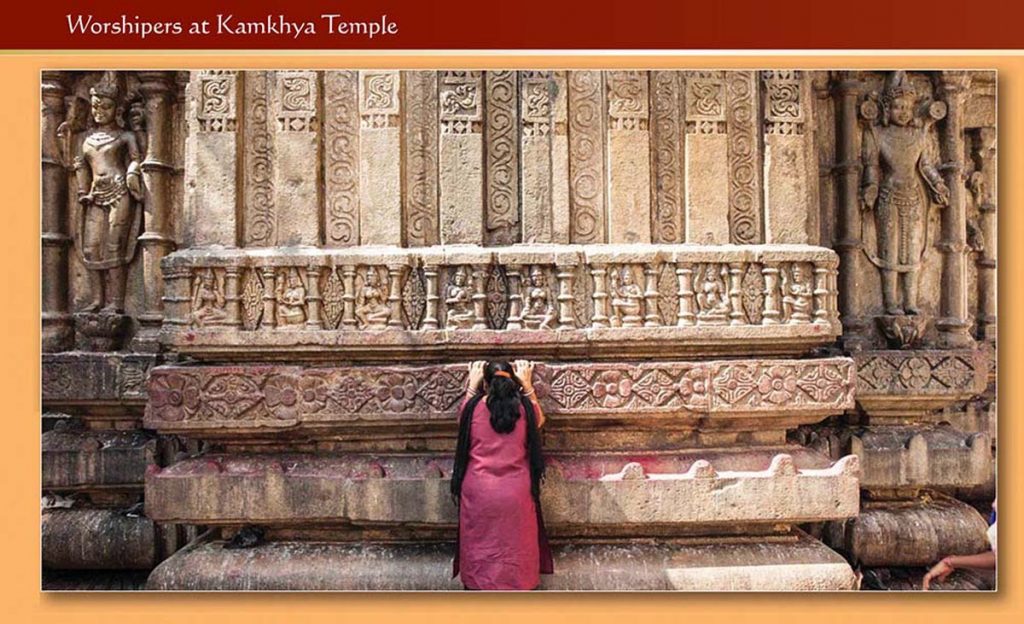

We started at the Ganesha temple, which was unexpectedly powerful, then moved on to the queue for the main sanctum. The inner sanctum is situated below ground level in a small, dark cave reached by a narrow, steep flight of stone steps. The sanctum contains a rock fissure naturally fed by an underground spring. It is this natural depression in the rock that is worshiped as Ma Kamakhya. The priest there invited me to touch the water of this spring and then sprinkle it on myself as the blessing from the Mother Goddess.

The whole experience of walking towards the sanctum to sprinkle the water took perhaps twenty minutes, but seemed much longer as the mysticism in the air here put me in a meditative state. Similarly, other devotees were in a mood of stunned amazement. Back outside, we slowly adjusted to the hectic activity. Many of the priests and devotees were dressed in red cloth, a symbol of Ma Kamakhya’s blessings. The color red is linked to the menses of the Mother Goddess, said to take place here once a year during the Ambubachi Mela in June during the monsoon season. That festival attracts hundreds of thousands, including many sadhus, tantrics and West Bengali Baul singers. The inner parts of the temple are closed to devotees for the first three days, with all devotees worshiping outside. On the fourth day the temple is opened again.

There are exquisite ancient statues on the outer walls of the sanctum where devotees reverentially pray by lighting incense. Another priest, Hemadri Sharma, 33, explained that while the time for darshan is short, the area around the temple is ideal for extended sadhana and meditation.

Two types of pujas are performed here, Vedic puja from morning to evening, and tantric puja, which is done at night in secret anywhere on the temple grounds. Allaying a common concern, Hemadri said that tantra is “just a system of worship, not a form of black magic and is not dangerous in any way.”

We encountered the area of the temple where animal sacrifice is done, though none was in progress at the time in the blood-stained shed. Viraj explained that one goat is sacrificed daily for the morning puja by a designated group of priests. More are sometimes offered during the day. With animal sacrifice falling out of favor—Shankardeva preached against it four centuries ago—a number of animals are simply donated to the temple by devotees and not killed.

Viraj himself finds the opposition to animal sacrifice rather hypocritical: “It is difficult to understand why, when so many animals are eaten each day by people all over the world, so much noise is raised when just a few animals are sacrificed and then consumed.” Hemadri defended the animal sacrifice, stating, “The whole idea is to have the animal attain moksha and be liberated. The ultimate aim is to grant salvation to the animal from the bondage of animal life.”

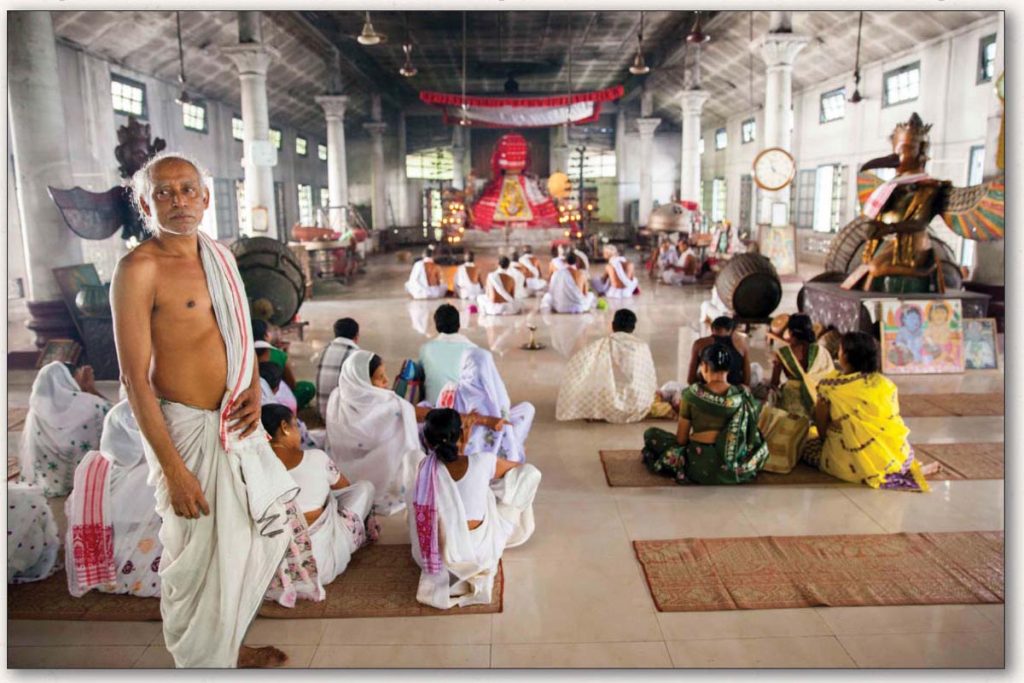

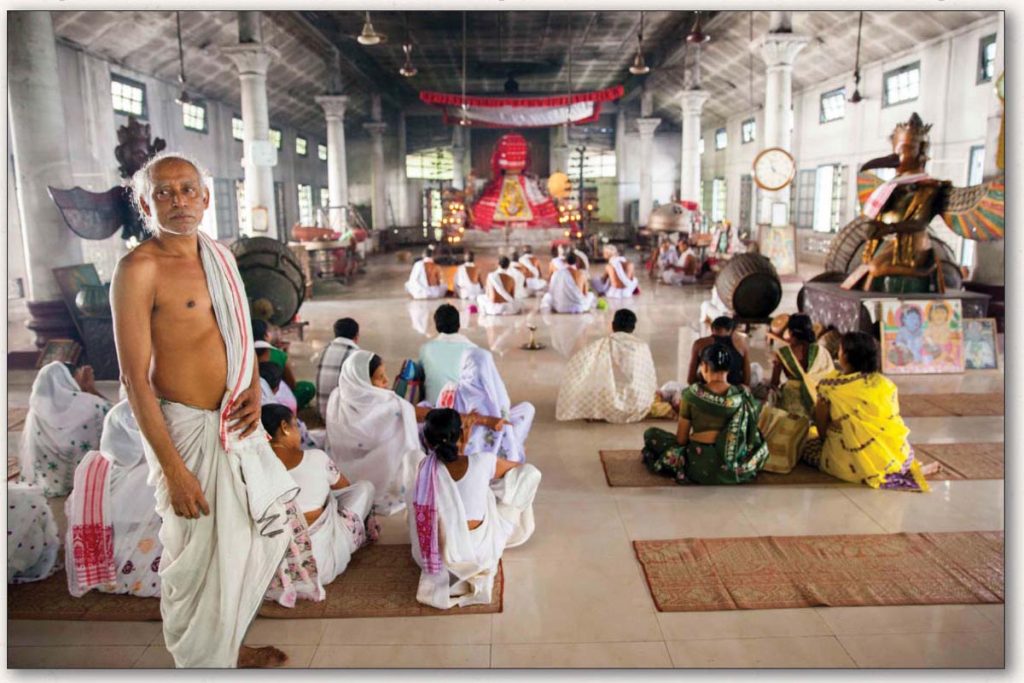

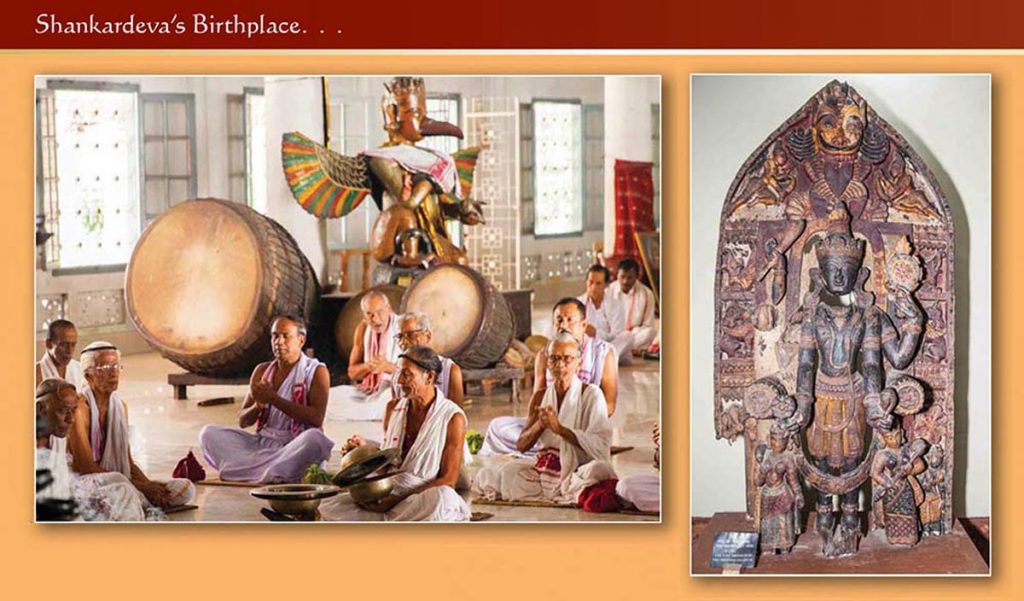

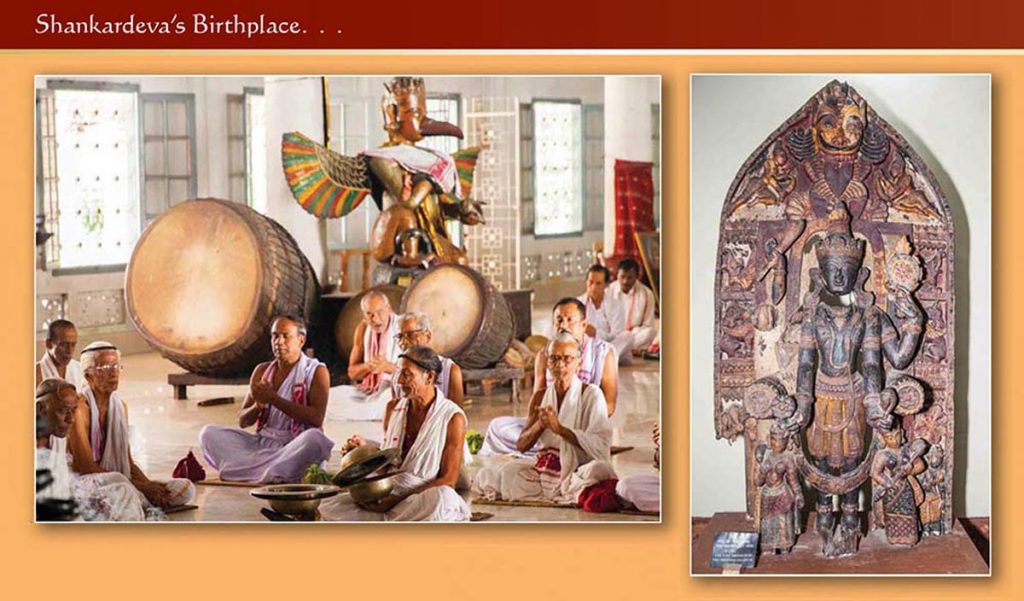

Shankardev’s Birthplace

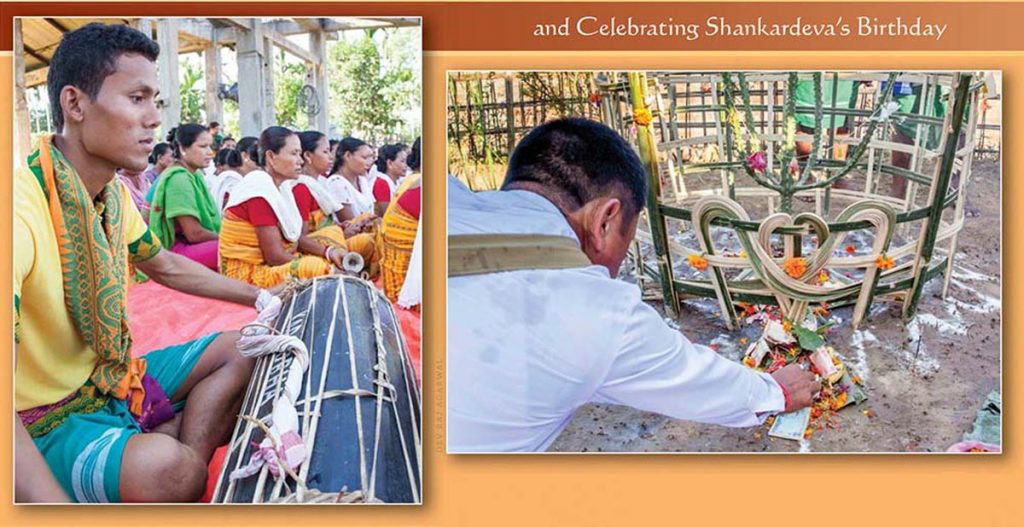

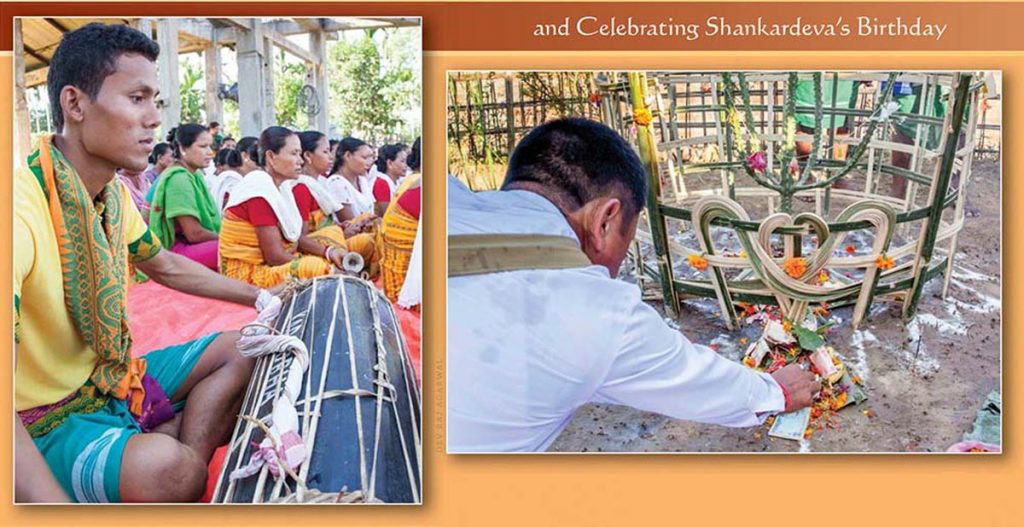

The most prominent Hindu saint of Assam is Srimant Shankardeva (1449-1568), a multifaceted individual who made Majuli, the world’s biggest river island, a seat of Neo-Vaishnavism and cultural capital of Assamese civilization. His birthplace, Barduwa Than, Nagaon, is 123 km east of Guwahati. Shankardeva remains unquestionably the most widely influential religious figure, especially due to the thousands of Naam Ghar temples set up by his disciples under the system of satras, or religious centers, found across Assam. They preach Ekasarna Dharma, literally, “shelter-in-one religion.”

Shankardeva was amazingly multi-talented: author, composer and Sanskrit scholar, painter, sculptor, dancer, musician and even weaver. Barduwa Satra was where he lived, wrote his books and taught. Preserved here and worshiped by devotees is a stone said to bear his footprints.

Inside Burduwa Satra’s huge temple, a large group of priests were chanting the names of Krishna accompanied by musical instruments and devotees all dressed in white clapping their hands. At the entrance we encountered the seven-tiered throne with the Bhagavat Purana placed on top as the object of worship. In Ekasarna Dharma, Krishna alone is worshiped, without a consort, a priest explained. His picture is displayed, but there are no Krishna statues, or murtis, for worship. The prayer hall has an ancient look, with its nine majestic doors, ornate statues of Garuda, tall multi-stemmed brass lamps and huge antique drums. Adjacent to the prayer hall is the Manikut, a sanctum where the temple’s valuables are kept, including Shankardeva’s personal copy of the Srimad Bhagavat Purana and other scriptures. A small temple outside holds a murti of Krishna, the only one in the entire compound, for devotees who wish to worship Him as having form.

We met Jugesh Atoi, who became chief priest here in 1965 at the age of 25. He said priest candidates come from all jatis, but to be a priest one must receive initiation. The Ekasarna Dharma is an egalitarian tradition, with all jatis regarded equally. In Assam, there are 800 satras in this tradition, some led by householders, others by brahmacharis.

Inder Mohan Saikia, a temple devotee and ex-army man, said they have four levels of initiation. According to one’s level, certain duties and responsibilities are taken on in the temple. With the second level, one must follow a vegetarian diet. Saikia told us of the eventful life of Shankardeva, who lived to 120. His main message was: “God is one; people worship different manifestations of the same one God.” Saikia concluded with this observation on Assam, “If you go 20 km from here, you will find the language has changed, and if you go another 20, the dress has also. This is how Assam is.”

Tirupati Temple

One major religious site in Assam’s capital isn’t Assamese at all, but a transplant from South India: the Purva Tirupati Sri Bala Ji Temple. A small clone of the famed temple of Andhra Pradesh, it was inspired by the Shankaracharya of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham and opened in 1998. The temple is on 20 acres of land, with the area immediately around the temple artistically landscaped and well maintained.

The Kanchi Shankaracharya directed the founders to include a temple to Goddess Durga, in respect to Ma Kamakhya. The temple and its many shrines were designed by Sri Ganapati Sthapati in typical South Indian style and painted a brilliant white. The facilities include a large yagashala and a fully equipped auditorium.

After passing through the 70-foot-tall rajagopuram entrance tower, we entered the main sanctum with its imposing 8-1/2-foot-tall statue of Lord Vishnu as Balaji, along with His consort, Mahalakshmi, and other Deities. The original Tirupati temple is famous for its laddu prasadam—a sweet made of flour, milk and sugar given to devotees after being offered to the Lord. Tirupati cooks were sent here to train the staff to prepare laddus to the same standard.

Pujas are performed in South Indian style, though here they follow the Pancharatra Agama, while Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh follows the Vaikhanasa Agama, according to Amodan Sharma, 47, one of the two chief priests. He said that most of the temple’s ten priests were trained at Kanchi Peetham. He notes that many Balaji devotees from Kolkata come here, to avoid the massive crowds at Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh. He explains that, under the influence of Shankardeva, “most Assamese worshiped God as formless, but still they like to have darshan of Balaji.”

Naraya Sharma, the temple administrator, shared that the main person behind the temple’s construction was B. M. Khetan, a leading tea businessman. According to Naraya, 2,000 people a day visit the temple, with 6,000 on weekends—a tenth of what Tirupati in Andhra sees on a daily basis.

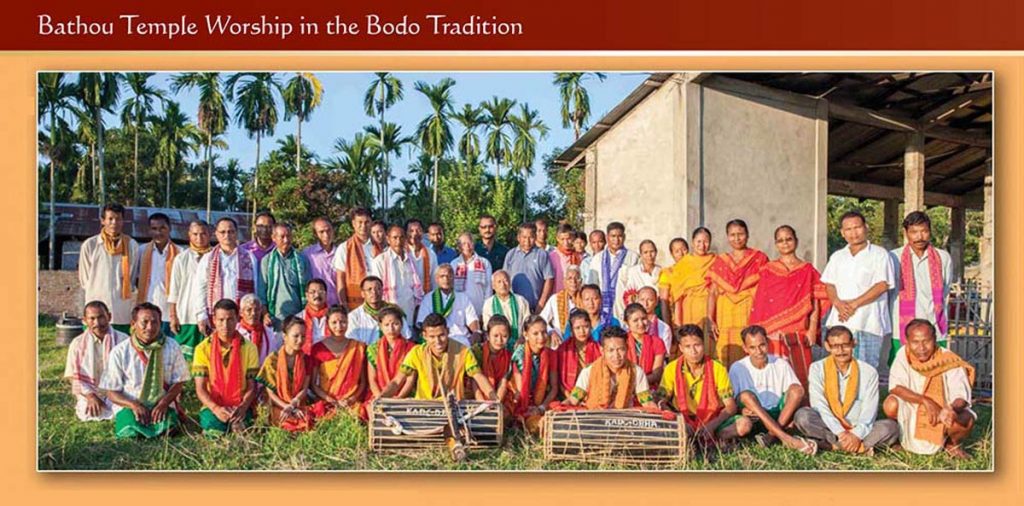

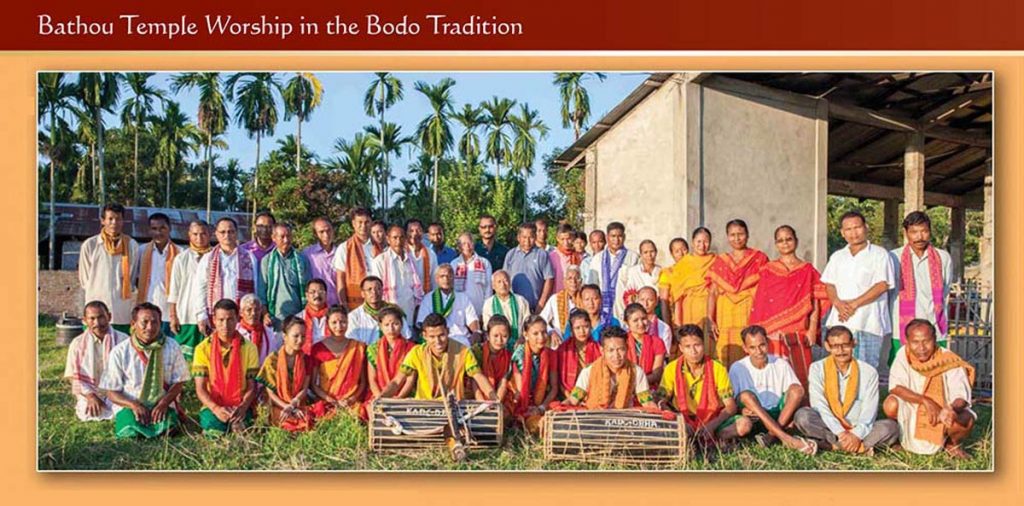

The Bodo Traditions

We drove 230 km from Guwahati to the Phulani area in Karbi Anglong district, a tribal area that is home to Karbis, Bodos, Kuis and many non-tribal people. Along the way we passed vast rice fields on both sides of the highway. We first visited a VHP project, the residential school, Reng Bong Hom Shishu Niketan. It was set up in 1979 and so named after a local tribal king and his wife. They have 244 students and 19 teachers who follow the government curriculum with added programs to teach religion and morals. The medium is Assamese. The school faces competition from better-funded Christian schools that also teach in English.

Sarsing Phangcho, a RSS volunteer, explained that people of his tribe, the Karbi, after which the district is named, prefer to have their children educated in English-medium schools. The Bodos in this area came from lower Assam after riots there between Hindus and Muslims. He said that among both the Karbis and the Bodos there are some who say they are Hindus and others who identify as just “tribals.” Both groups are largely non-vegetarian. Twenty-five percent of Karbis are said to have converted to Christianity, mostly as a result of studying in the Christian schools.

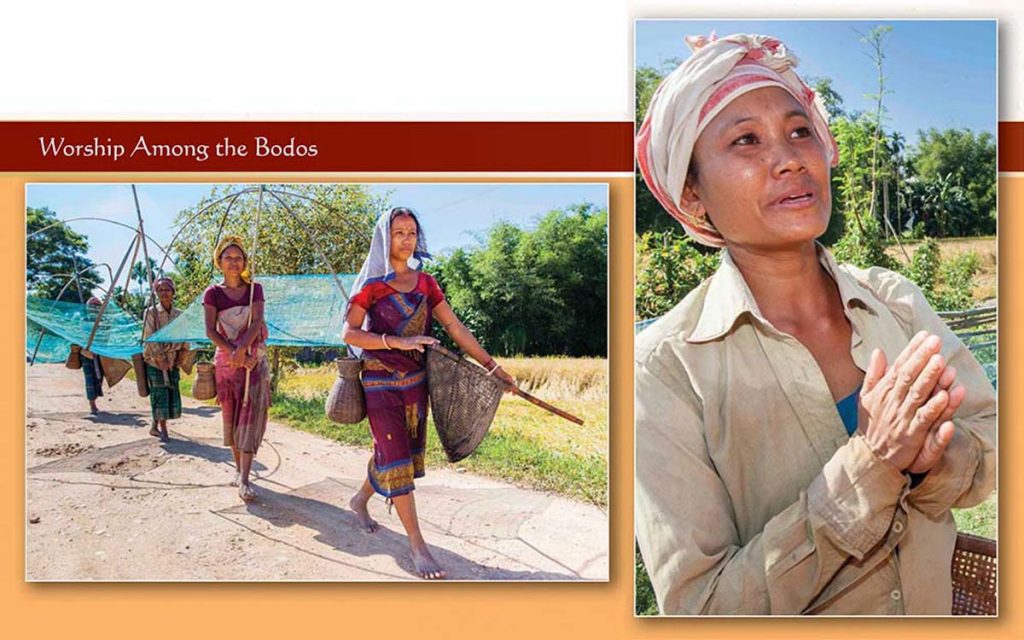

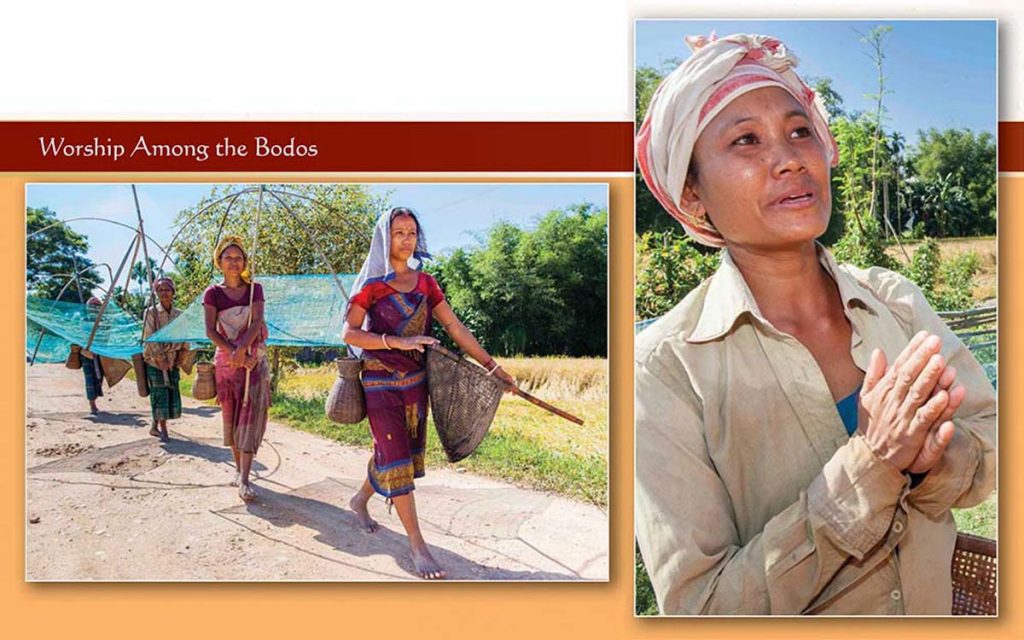

From Phulani we drove through interior villages to Langhin Manikpur. By chance we encountered a group of Bodo women walking on the road, nets in hand and carrying baskets of fish they caught that morning. In retrospect, this was one of the most touching and poignant moments of our visit. We spoke with one of them, Champa Basumatari. I was amazed at the divinity shining on the face of this tribal lady. Her poise and confidence while communicating with me in Hindi would match well with any lady in India’s metropolitan cities. She looked blissful and contented. I was deeply touched when she said she gives preference to her religious life over material progress and intends to pass those values on to her children.

She kindly invited us to a nearby relative’s home, our first visit to a tribal house. Here we witnessed the Bodo worship of the sijou plant (the medicinal cactus euphorbia splendens) growing in front of the home and protected by a woven bamboo fence. The Bodo religion is called Bathou, meaning five principles—air, sun, earth, water and sky—parallel to the familiar five elements air, earth, fire, water and ether. The Supreme God, whom they worship through the sijou plant, is called Bathoubwrai, the “Elder” who created the five principles and is omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent. Champa said they treat Bathoubwrai as Siva. His consort, Mainao, is revered as protector of rice fields. Some regard Her as a form of Parvati; one Bodo elder identified Her with Lakshmi. There are minor Gods as well. Worship in the Bodo faith is done at home, at Bathow temples and during several large community festivals each year, notably Bwisagu, the Bodo New Year Day, in April.

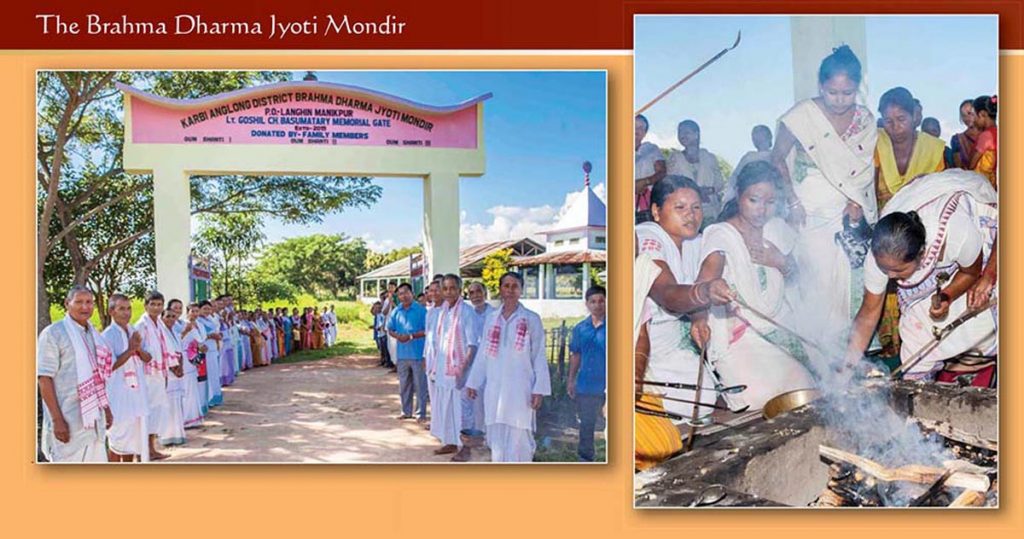

We were visiting two temples here, one along the lines of the worship of Bathou we just saw, and the other a more recent innovation: the Karbi Anglong Brahma Dharma Jyoti Mondir in Langhin Manikpur. This is a temple of the Brahma Dharma movement introduced to the Bodo people in 1906 by Sri Sri Kalicharan Mech, a Bodo. Brahma (or Brahmo) Dharma is an offshoot of the Brahmo Samaj, a Hindu reform movement founded in the late 19th century in Kolkata, Bengal, by Ram Mohan Roy.

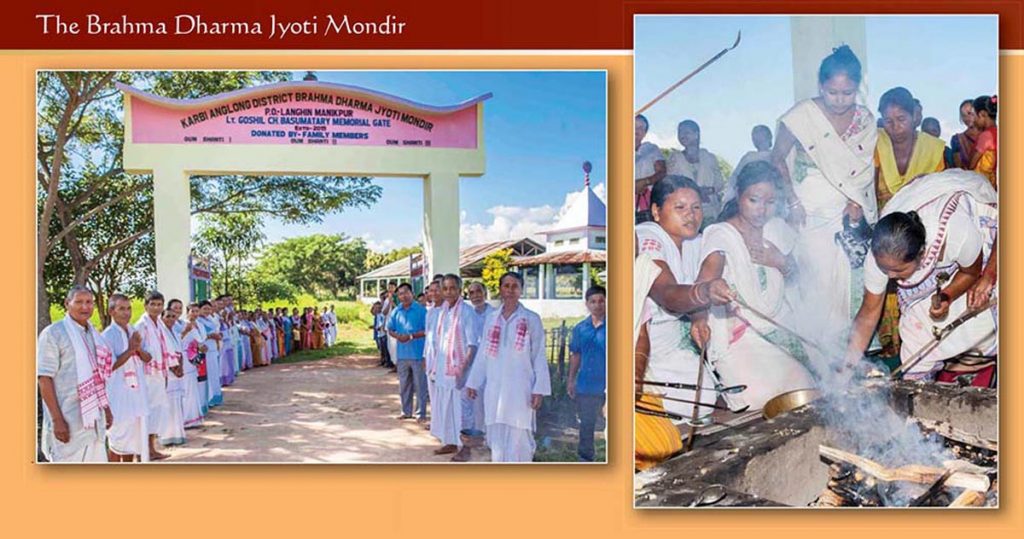

A large group in elegant dress greeted and paraded us to the open-air temple, where we joined an elaborate yagna, with over a dozen priests chanting Vedic hymns and mantras in worship of Agni, the Fire God. At the end of the rites all the devotees prayed before the fire, kneeling down and placing their foreheads on the floor, chanting, “om purnaparam brahma jyoti swarupaye namo namah,” which means, “We salute the highest Brahma, Who is in the form of light.”

The Brahma Samaj believes in six commandments of Paramatma, God: 1) keep the universe always clean; 2) treat all creatures equally and try to solve their problems; 3) offer sweets and scented articles to the fire and let others also offer; 4) chant om purnaparam brahma jyoti swarupaye namo namah; 5) bear the light, jyoti, in the eye or on the forehead faithfully; 6) be attached to He Who is omniscient.

While rooted in tradition, the young tribal women of Brahma Samaj seemed educated and modern in their outlook. Many were using mobile phones to take videos and click pictures of our visit.

Our final destination for the day was the Bathou Temple. As happened at the Brahma Samaj temple, we were greeted not as a reporter and photographer, but as honored guests. Over a hundred temple members and the officials of the All Bathou Maha Sabha were there to welcome us, beginning with the traditional Bodo dance, Baguramba (see photo on page 18).

The temple was simple, an open hall with the sijou plant representing the Bathou God in its bamboo enclosure at one end. The worship, on the other hand, was quite elaborate, in part because, in addition to Bathou, many other tribal Gods and Goddesses were there to be honored. All the eighteen sacred items in the open around Bathou God were symbolically connected to specific native Gods. The rites were is accompanied by constant bhajan and kirtan.

It is difficult to express how moved I was as I worshiped Bathou God. This was the first time I connected to God in the interiors of the tribal lands and experienced the power and faith of tribal people. Many regard Bathou God as Lord Siva, others do not. But as a Saivite, I found this worship profound and more than uplifting enough to make me forget the grueling day we were completing with seven hours on the road. I had been allowed a glimpse into the mystic life, tradition and culture of this colorful community of Assam who live so close to the divine.

Education Projects

Education with a Hindu slant was one topic we were tasked with documenting in Assam. We got quite a sampling, ranging from a driving academy and sewing training center to the one-room schools of Ekal Vidyalaya in remote villages and the Shankardeva Vidya Niketan, a premier Guwahati school popular with parents for its high standards and Assamese ethos. These schools are privately funded and do not take government money. All try to instill in students love of country and devotion to the Hindu traditions.

Jan Kalyan Trust, associated with the RSS, operates vocational schools across India, one of which was the driving school in South Guwahati. Bharat Kumar, an RSS lifetime worker, founded it in response to a lack of Hindu drivers in a profession dominated by Muslims. He told us of multiple problems from harassment of Hindu passengers to difficulties with full-time drivers working for Hindu families resulting in cases of “love jihad,” where a daughter drawn into marriage is forced to convert to Islam.

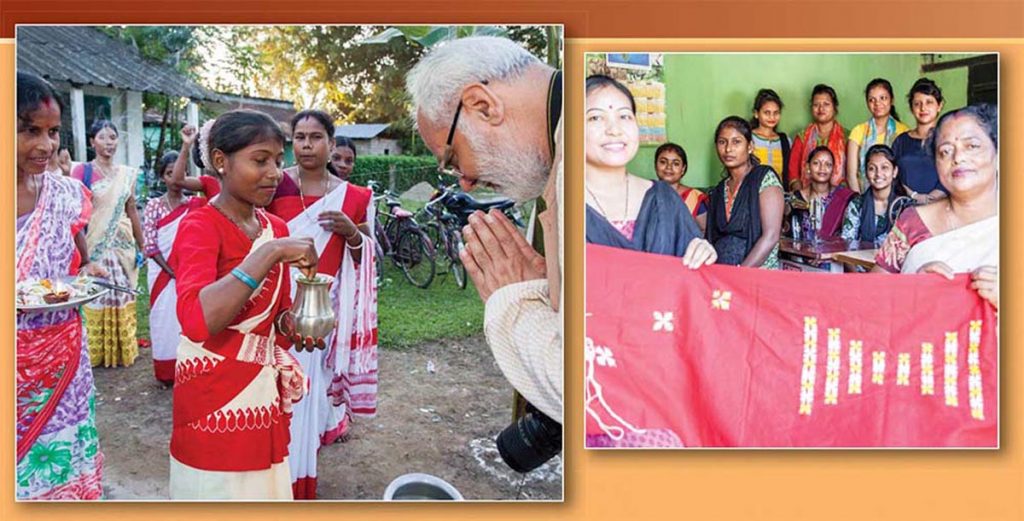

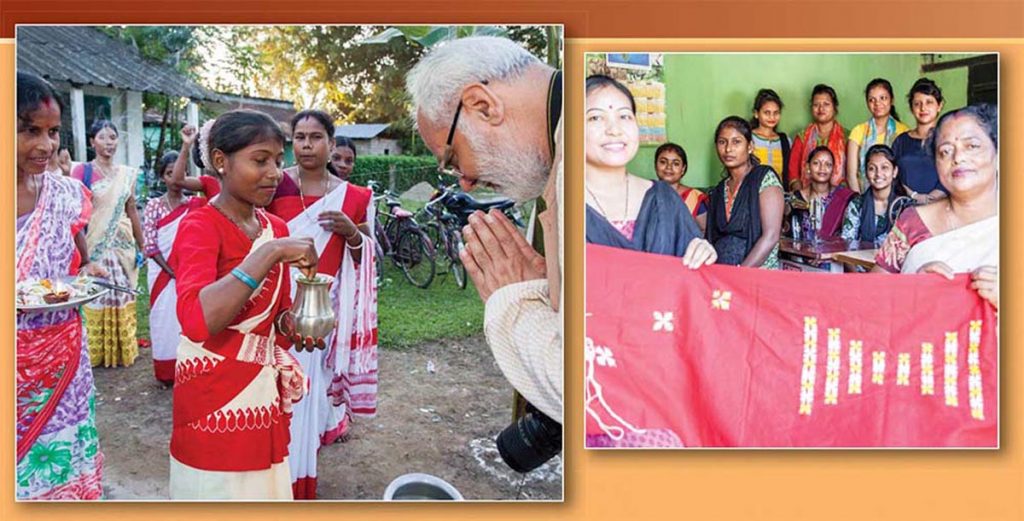

At Jan Kalyan’s small sewing school in Shankardeva Nagar, the students welcomed us with Vedic chanting and bhajans they are taught as part of the curriculum, along with basics of Hinduism through a book in Assamese, Ideal Hindu Home. Ladies enthusiastically showed us the various Assamese ethnic motifs the use in their embroidery work. Many ladies were wearing Assamese outfits they had designed and sewn themselves—using skills they are finding quite marketable. Incidentally, the people here, as a whole, are impeccably dressed in traditional garb.

The Shankardeva Vidya Niketan School is one of sixteen run in Guwahati by Vidya Bharati, part of the educational wing of the RSS. This school is 36 years old and has 700 students. It maintains a standard as good or better than local Christian missionary schools. Four languages are taught: Assamese, Hindi, English and Sanskrit. Students regularly score well on tests and have a reputation for good conduct and refined manners, according to Pranjeet Pujari.

Every class begins with a few minutes of meditation, and the day ends with the entire school singing in unison Vande Mantaram, the national song in praise of Mother India. As the children departed, hundreds touched the feet of the principal, Chitra Medhi Das, seeking her blessings as they left for home.

Pranjeet told us their city schools are well funded, but those in tribal areas face financial difficulty. Christian schools in those areas are free. “We call their strategy of influencing the impressionable minds of our kids ‘silent killing.’” The missionary schools were here long before Vidya Bharati was established.

In the evening we visited the headquarters of Sewa Bharati—which included a small youth hostel for tribal boys—in the Adingiri area. It was during this visit we first became acquainted with Assam’s early sunset at this time of year (October). It became pitch black shortly after 5pm! India does not observe daylight saving time, and Assam is on the eastern end of the country’s compromise of three time zones made into one. The practical consequence of this was traversing several kilometers of poor road in the dark.

During our visit, a conference of RSS volunteers was taking place. The center frequently hosts such functions. Sewa Bharati manages various education, health, relief and rehabilitation projects. It was currently exam time, so the boys were deeply immersed in their studies, but they took a moment to greet us with a Vedic chant. They all study at a nearby Vidya Bharati school.

The 35 boys belong to 17 out of Assam’s 34 districts, as well as some neighboring states. They encompass a wide range of religious practice and belief, according to Vikal, but each is encouraged to follow his own tradition. Some, he explained, follow the Bathow God. There are children from Mizoram who practice Buddhism, others from Assam who follow Shankardeva and the Bhagavat Purana, while still others, from Meghalaya, who follow their tribal form of worship.

Vikal explained Sewa Bharati’s approach: “We do not ask the students to worship any Hindu Gods or Goddesses, but instead ask them to worship Mother India, the heroes of Assam and even the rivers of the Northeast. The basic idea is to inculcate honor and love in them for their native roots and their country. We do not interfere with their individual way of worship. It is the policy of all Sangh Pariwar organizations to help people maintain their individual identities. This contrasts with the Christian missionaries who are engaged in changing their identify by conversion. There are such missionaries active in this district right now.”

The Ekal Vidyalaya project at Kathiatoli, Kandoli Tea Estate, is about 200 km east of Guwahati. We arrived as the tea workers—mostly women—were winding up their day, having their harvest weighed and heading home. They were tired, and not in the mood to talk, but were willing to be photographed, giving Thomas a marvelous opportunity. I had seen women carrying heavy packages of picked tea in movies and TV serials, but in person it was a moving experience.

When we reached the school, the young girls were ready to welcome us by washing our feet while chanting Vedic hymns and singing bhajan. In North India men do not normally accept women doing this for them. With folded hands, I requested them to greet us by putting a tilak on our forehead.

The children gave a short presentation by chanting Vedic mantras and some prayers, but given the lack of light, were then sent home. The electrical supply to the school was unreliable, and a clear hindrance to its functioning. We were able to talk with the school’s teacher, Pushpanjali Munda, who said that 40 to 50 come daily. Most attend government school in the morning; but for some the Vidyalaya is the only schooling they receive. Assam has some 2,200 Ekal schools, each with a single teacher.

During our stay in Guwahati, we visited Vivekananda Kendra at Paan Bazar and later the Vivekananda Institute of Culture situated on the banks of Brahmaputra River in Uzan Bazar. The Kendra is a spiritually oriented service organization working throughout the country since 1972. According to Meera Kulkarni, a senior organizer, they run a chain of 22 Vivekananda Kendra schools in Assam and 139 branches of a project called Anandalaya, which provides non-formal education and hostel facilities to children of tea garden workers. They also operate extensive medical and rural development projects. These efforts are managed by 32 full-time workers in Assam with the help of hundreds of volunteers in 39 centers. Religious education and yoga are a part of many of the programs.

The m was set up in 1993 to nurture the Northeast’s indigenous cultures through scholarly seminars, research, documentation and publications. According to Pranav Jyoti Brahmachari, they host frequent intellectual and cultural programs, as well as maintain a library and research center. They sponsor researchers to live among the various tribal communities to record their life and culture, with a focus on understanding the aspects of belief and culture the tribes share with each other and the rest of India.

Insights on Assam

Dr. Biren Gogain, of the Ahom tribe, is an anthropologist, former bureaucrat and ardent devotee of Lord Siva whom we interviewed in Guwahati. Some excerpts from that free-wheeling discussion:

Before the advent of Vaishnavism in Assam, Lord Siva and Mother Goddess Parvati were the presiding Deities of all groups in what was then called Kamarupa. The earliest forest people were the Khasia and Jayantia. Then came the Indo Mongoloid groups in large numbers through Tibet and Bhutan. They pushed the Khasi and Jayantia to the hills. Later people came from China, Myanmar and elsewhere. Why it is that they all adopted Saivism I am not able to answer. My research shows the tribals worshiped Siva in many different ways and forms, such as the Bathow God.

Vaishnavism came to this region in the 15th century during its heyday. It was at that point in time the kathas of Lord Krishna were injected into the psyche of the people of this region. Shankardeva was influenced by a disciple of Adi Shankaracharya who propagated Vishishtadvaita philosophy in which no duality of God is accepted and no female principle required. To Shankardeva, Radha was just a disciple of Krishna. He also did not believe in ritualism but taught that one could approach God directly through the recitation of His name and avoid all the middlemen.

Assam is a hotbed of casteism and tribalism, because most of the people here are tribals. Some are included in the Scheduled Castes and Schedules Tribes list in India’s constitution, others are not. Those listed get reservations in education and jobs; those who are not are agitating to be listed. I always say that Ambedkar did a disservice to the nation by putting these schedules in the constitution and not as an administrative order with a set time limit. Homogenization is not possible, as the tribals would like to remain tribals and not become a part of the mainstream.

The Nagas have lost their tradition to Christianity. They now go and listen to Christmas carols and no longer worship their own Gods and Goddesses. This is how Christianity has played havoc with the culture of our tribal regions. In Mizoram, there is even one small group, the Bnei Menashe, who believe they are a lost tribe of Israel. Since 1970 several hundred have emigrated to Israel. The people of Arunachal, on the other hand, have retained their own culture and not converted. Here in Assam, this kind of situation was prevented because the Ahoms are very strong and Shankaradev preached unity in diversity.

When tea was discovered in upper Assam, it was found to be even better than what was grown in China. The local population did not want to work the plantations, so the British brought workers from Bihar, Telangana and Mysore. Many died during the journey to Assam or were treated badly upon arrival. The tea garden workers you see today are descendants of those people.

Delhi needs to understand Assam in a better manner. The “Look East” policy is good, but the biggest obstacle to development is the “chicken neck” corridor with India (see map, page 20). There is a railroad, but not enough trains. Transport by road is very expensive. If the route were severed by militants, the Northeast would be completely isolated. Assam only produces rice, even most fish comes from the outside. Industrial development has not taken place here because transport is so costly. We need a route through Bangladesh.

Five million Bangladeshis entered Assam in 1971. These immigrants are a big problem; they are eating into the vitals of the Assamese race. They put the identity of the state in danger. There is talk of giving citizenship rights to the Hindu Bangladeshis. But if that is done, then eventually the Muslim ones will also be given an order in their favor by the Supreme Court. These migrant Bangladeshis should be distributed all over India. This is a very sensitive issue and if not handled properly the present BJP ruling party will be beaten down. Just shouting “Hindu, Hindu” will not win them elections in Assam.

Conclusion for Part One

At the first sight, Guwahati appears to be like any other Indian cosmopolitan city, with large and glamorous showrooms, malls and luxury hotels lining highly commercialized roads in the posh areas around the city’s center. However, within a few days of our moving in and around this ancient city we experienced its many unique treasures. The first and oldest is the mighty Brahmaputra River, “Son of Brahma,” a rare male name for an Indian river. Then there is the world-famous Ma Kamakhya Temple, which we felt truly blessed to visit. We traveled hundreds of kilometers to Barduwa to visit the birthplace of Srimanta Shankardeva. Our guide took us to interior tribal areas where we encountered the traditions of the Bodo, Ahom, Karbi and other tribes, and observed the manifold activities of Ekal Vidyalaya, RSS, VHP and other Hindu organizations.

Our fascinating spiritual exploration of the lives and traditions of Assamese Hindus will continue next issue as we shift to Dibrugarh, center of the tea country. We visit with the tea workers, whose forefathers were brought here by the British in the 19th century. We take a ferry boat across the Brahmaputra to the world’s largest river island, Majuli, seat of Neo-Vaishnavism and the religion known as Ekasarna Dharma propagated by Srimant Shankardeva through his Vaishnava satras. In Majuli we met the world-famous mask-makers and the Mising tribals. After traveling to the ancient Siva temple at Sivasagar and the famous Tilinga Mandir, or Bell Temple, in Tinsukia, we spend our last day among the large Nepalese Gorkha community here. Stay tuned, as they say, for our final coverage on the amazingly diverse land of Assam.