By AJITH BRIDGRAJ

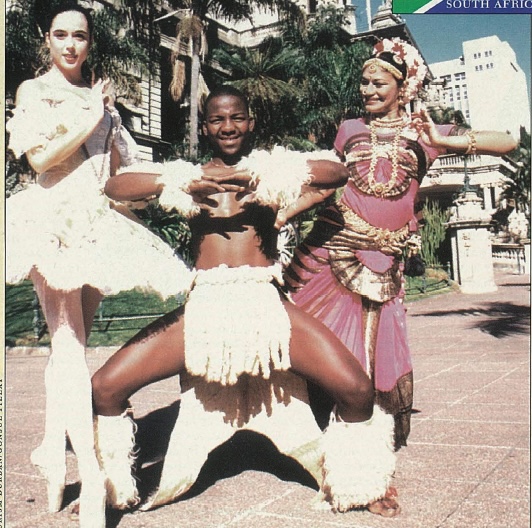

Hindus in South Africa face the same cultural conundrums as those in other countries. While Eastern traditions of art, music, dance, drama and storytelling thrive among Indian as well as Colonial and African communities, the core question remains: How much should we assimilate, integrate, adapt and transform our traditional arts in order to better fit into our locale, or in response to creative fervor? Debates along these lines rage within social circles, and the answers remain largely inconclusive, seeming to be more a matter of individual choice and opinion than a cultural ethic.

Even close sisters disagree. Heeranju and Netra Prabdial are young tutors of Indian classical dance. They were enrolled for training as children, and both have furthered their talents out of genuine interest and determination to develop artistically. But they differ somewhat on the issue of cultural fusion. Heeranju, the younger, expressed disquiet that many teenagers, especially those in secondary schools, are ashamed of their culture and traditions. “They are becoming too Westernized,” she admonishes, arguing that, “The promotion of Hindu culture is crucial in a multicultural country like ours in the midst of the present circumstances of transition. I would not like us to lose any aspect of Indian art through assimilation. We need to preserve the Indian identity rather than submerge aspects of it in the interests of a broader South African identity.” Netra, on the other hand, is not so convinced. “I am not totally opposed to amalgamation,” she counters. “In sacrificing some aspects of Indian art, we would be enriching ourselves by drawing from another of South Africa’s cultural groups.”

Heeranju also blames a lack of understanding of Indian languages as fostering youth uninterested in Eastern songs. “Many are unable to understand the rich and profound Indian lyrics,” she laments.

With these issues at the fore, in April, 1998, the Dr. Salem Jayalakshmi International Centre for Performing Arts, Durban, in conjunction with the University of Durban-Westville, staged the International Carnatic Music Conference, focusing on the theme of “Carnatic music into the 21st century.” The assembly sought to envision the direction that Carnatic music in particular was headed, noting that, “In the 20th century, all ragas are played on violin, harmonium, flute, clarinet, guitar and saxophone.” All of these, except the flute (if it’s bamboo), are of Western origin. They also speculated that “In the 21st century, all ragas will be played on keyboards as well as adopted by other forms of music.” They urged an exploration of “harmony in ragas.”

Raj Govender, the Regional Head of Arts, Culture and Youth Affairs for the government of KwaZulu Natal, one of South Africa’s nine regions, feels no threat to the Indian identity. “Indians have kept their culture alive through the observance of religious and cultural festivals, especially in the rural areas. They brought with them simple musical instruments, which they preserved and developed over the years.” Still, Govender, concedes, Hindu arts have undergone transformations recently to suit the masses and the youth. “However,” he says, “the basic elements of song, music and dance have been retained.”

Govender proudly reports that annual Government funding to linguistic and cultural organisations by the Department of Arts and Culture has greatly aided the promotion of Hindu art forms in South Africa. Recipients include the Hindi Shiksha Sangh, the Natal Tamil Vedic Society, the Andhra Maha Sabha and the Gujarati Parishad. Awards range from us$100?$2,000.

Marveling at the large numbers of Hindus, especially youth, who pack temples on auspicious festivals such as Sivaratri, Govender points to an art and culture rejuvenation among Indians. He cites the enthusiastic observation of festivals such as Holi and Pongal, and he boasts that the observance of Diwali has never waned in the more than 138 years of Indian presence here.

Fashion foibles: With no apparent regrets, South African Indian women no longer limit themselves to any specific mode of dress. Often their clothes–be they trendy Western attire, ethnic African fashions or elegant Eastern wear–are dictated by the decorum of the occasion. This was not always so. Seventy-four-year-old Pandita Nanackchand, grandmother of Heeranju and Netra, says that during her youth, dresses worn by girls had to extend beyond the knees, preferably down to the ankles. The wearing of saris was virtually obligatory once girls had entered their early teens, while wearing jeans and pants was altogether taboo.

The Pandita’s daughter, Ishara Prabdial, mother of Netra and Heeranju, believes Indian women are generally loyal to their traditional attire and take pride in wearing Eastern outfits, but that circumstances do not always allow them to do so. “Socio-economic considerations demand that women have to find employment, and they often dress in what is comfortable or prescribed by the employer,” she says. Heeranju states that if she is attending a prayer or wedding service, she would definitely dress in Indian attire, but feels that there is nothing indecent about wearing shorts if she has to visit the beach. Netra concurs, “The wearing of jeans, T-shirts and takkies are the norm, but on religious occasions, the Hindu female students generally dress in traditional garb.”

Netra has noticed a significant interest by non-Indian students in traditional Indian dress and adornments, including nose rings. So if Indians are diluting their dress to some degree, there is some small compensation provided by the fond embrace of their ethnic neighbors. 1Ú4