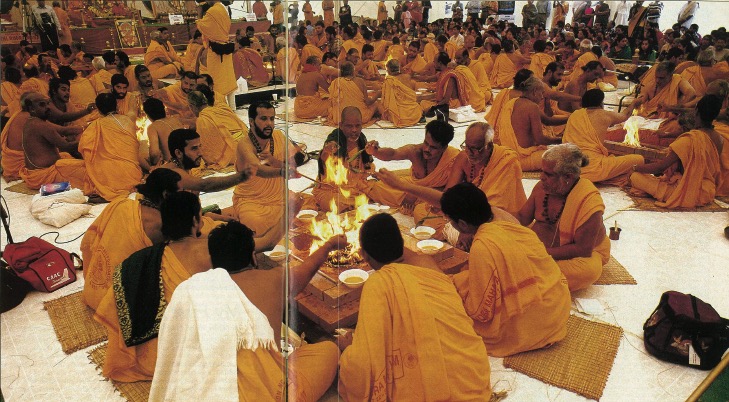

FOR ELEVEN DAYS IN AUGUST, DIVINE Vedic chants resounded through the tranquil Poconos mountains of Pennsylvania. The Ati Rudra Maha Yajna,”very great worship of Lord Siva,” was performed for the first time on American soil, and witnessed by 6,000 enchanted devotees. One-hundred-twenty-one Vedic priests surrounded 11 fire altars in a huge yagasala (worship hall) set up for the event at the Sringeri Sadhana Center in Stroudsburg. Following a ritual formula set thousands of years ago, priests chanted “Sri Rudram,” the most sacred of Vedic chants to Lord Siva, 11 times a day each day for a total of 14,641 individual recitations.

The ritual’s official purpose was to enhance America’s prosperity, though pre-existing prosperity on the part of the organizers was required. The event cost US$600,000 (Rs 2.2 crore). Nearly half was used to bring 81 eminently qualified priests from India for the ceremony. Permanent improvements at the Center consumed $100,000. The affair proved as costly and as complex to organize, calculated one devotee, as 11 kumbhabhishekams (temple dedications), usually the biggest spectacle sponsored by a temple. The yajna was managed by the Indian-American devotees of Jagadguru Shankaracharya Sri Sri Bharathi Teertha Mahaswamiji of India’s renowned Sringeri Math, who blessed and guided each detail from afar.

Why go to all this time and expense? For no less a goal, stated the event’s general chairman, S. Yegnasubramanian [see “My Turn,” page ten], than to rescue the Hindu priesthood from social and economic extinction. “We bring musicians and dancers from India to the West,” he told Hinduism Today. “We bring temple architects and sculptors. They all make money and receive respect. As a result, these exponents of the fine arts, which are the offshoots of the Vedas, get so much encouragement. But what are we doing to encourage the Vedic pundits, those who know the Vedas, without whom this dharma will die?”

In India, fewer and fewer brahmin families are sending their children to the pathasala training schools as has been done for thousands of years, bemoaned Yegnasubramanian. Fearing a life of penury for their children, they educate them as doctors, engineers and scientists. India’s temples still have priests, but they are a depressed, even desperate class. “Go into any village in India,” says T.S. Shanmuga Sivacharya of Chennai, son of eminent Saiva priest Sambamurthi Sivacharya, “and the poorest, most broken-down house will be that of the priest. There are very few full-time priests, because of poor economic conditions.” Respect is waning. “When a politician comes in,” Shanmuga complained, “we are expected to stand up. At least Sri Lankans still respect the priests, and among them the politicians stand when the priest enters.”

Shanmuga laments, “Fifty years ago priests were looked upon as representatives of God. They had patrons. They had a respectable position in society. Today the priesthood suffers from low pay and disrespect. It is undergoing extinction. This trend must be taken very seriously.” One can cite numerous reasons for the situation in India–colonization, secularism, Marxism, Westernization–but the fact is that the same plight is faced in growing measure by all the world’s religions. In America, for example, so few Catholics are entering the seminary that the church must import clergy from abroad (including India) to meet its obligations to parishioners, and the average age of Catholic nuns is an astounding 65.

Yegnasubramanian and several associates are themselves a product of this trend. Their ancestors were priests who, in one or two generations, educated their children to become doctors, businessmen and engineers. Recent visits to India have left Sringeri devotees painfully cognizant that the Hindu priesthood in India may indeed be slated for the endangered species list. Ironically, they noted, the opposite is true in the West. The clergy in America are an esteemed class, roughly the professional peers of attorneys or doctors. As Yegnasubramanian had seen, other exponents of the Vedic arts have been honored in the West, and this has translated into renewed regard back in India.

“I told my colleagues,” he reminisced, “‘Let’s make an international Maha Yajna (great sacrificial offering) and bring a large consignment of priests from India. We can make so much noise about it that the priests throughout India will realize that there are prospects for them over here. It will motivate them to send their children for priest training. It will increase their self-esteem.'”

A December of 1996 visit to the Sringeri pontiff near Bangalore earned the guru’s blessings upon the plan. Then, with the help of Sringeri administrator V.R. Gowrishankar, the team set out to organize, in just eight months, the largest Vedic ritual ever held in America. They succeeded for two reasons. First and foremost, as devotees of a single guru, they proceeded in harmonious cooperation to fulfill his intent. Second, each is a highly accomplished individual. Yegnasubramanian is an eminent research scientist. Ravi Subramanian, who provided logistical support, initial financial backing and expertise, runs a top-notch software company. Likewise, trustees T.R. Ramachandran, S. Ramakrishnan (Dubai), V. Panchapekesan (India), G. Viswanathan (Hong Kong), Aju Daswani, Ram Mehtani (Hong Kong) and many others who helped, such as Sharad Trivedi, are all experts in their fields.

Two years earlier the group had come together to create the Sringeri Sadhana Center in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, 200 miles west of New York City. The property was previously the Rajarajeswari Peetham, which after a series of staffing changes, was unable to sustain itself financially. The new center is an official branch of Sringeri Math, the first outside India. Their intent is to create and implement guidelines for modern life based on the philosophy of Adi Shankara [see page 30], even develop the site as a learning center rivaling Harvard or Yale. Presently the center conducts retreats for children, and next year plans training camps for entire families.

Organizers say a minor miracle occurred prior to the Maha Yajna–the US Consulate in Chennai granted the 81 Indian priests visitor’s visas with no personal interviews and no rejections. Immigration attorney Michael Phulwani attributes the success to proper presentation and a knowledgeable US Consulate. A century ago, priests would have been subject to rigorous prayaschitta (penance), even loss of caste, for “crossing the ocean.” With today’s air travel, however, most priests deem that a simple penance is sufficient to efface any demerit or impurity. To fill out the yajna’s 121 seats, 40 qualified priests were recruited from within the US, some of whom preside at temples here.

Unexpectedly, the priests were invited to join the India Independence Day parade. They marched en masse in ochre-colored robes through the streets of Manhattan on August 17, thrilled to see New York up close as they chanted the Vedas. Some among the 50,000 onlookers were so delighted they prostrated as the Vedic liturgists passed by. The priests returned to the Poconos that evening to continue the yajna.

Invited by the organizers, Hinduism Today’s managing editor, Tyagi Arumugaswami and production/distribution manager, Tyagi Kathirswami, attended as representatives of publisher Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. We arrived on the eighth day to encounter a palpable spiritual force. In lilting Sanskrit and practiced unity the priests hastened through the day’s first ten recitations; then slowly and deliberately intoned the eleventh while offering ghee to the sacred fire. Pandit Chandra Sekhara Sharma presided as chief priest. Swami Narayananda Bharati performed exquisite devotional songs throughout. Each afternoon, a variety of rare Vedic rites took place.

Vedic ceremonies differ outwardly and inwardly from the Agamic tradition of elaborate temple ritual in which offerings of flowers, water, lights, etc., pour forth deep religious feelings toward the Deity. Vedic rituals bypass the devotional element and propel one immediately into a meditative state. Sarala, a Chennai devotee of Sringeri who chanted along with the priests with others, said, “Often I stopped because the sounds induce meditation so beautifully.”

Belur Krishnaswami Sridhar, 38, a priest from Bangalore, was delighted with the event. “Too good,” he called it. “Most surprising,” he said, “is that we have seen a lot of English people, Americans, who could meditate and chant the mantras. This amazed us priests.”

Young people there were few. Many spent the Labor Day weekend getting ready to head for college. One parent thought children were not allowed. Jehi Jayaraman, age 8, did come and enjoyed it, “Because I can chant along, I think it’s fun.” Others did not, like the clueless 16-year-old who said, “I don’t know what’s going on. They should have had workshops on why they are doing it on such a grand scale.”

Yajna is an esoteric practice combining the science of mantras, sacred sounds, with the use of fire to transmit offerings to a higher plane, to “nourish” the devas. But none of the youth and few of the adults could explain just how that works. Dr. Sankar Sastri had a plausible answer: “We are told by great seers that the performance of austerities and yajnas is what keeps the heavenly devas prosperous. And when they prosper, the whole universe prospers.” T.R. Ramachandran, editor of Sringeri’s Tattvaloka magazine, concurred, “It is called in Sanskrit drishta and adrishta, which are seen and unseen effects. When we work in the material world, it is toward seen results. But these mantras, chanted in the right rhythm, create an unseen effect which allows things to be achieved in the material world.”

Did these rare rites succeed in their noble aims? As for prosperity in America, the Standard & Poor index (mirroring 70% of US stock, valued at $6 trillion) was 907 on August 21, a day before the sacrifice, and hit 945 on September 26. That’s a jump of 4.2%, a whopping increase in overall value of $252 billion, or about $1,000 for every man, woman and child in the country! Not a bad five-week return for $600,000 invested in the Maha Yajna! Then, too, each priest returned to India $1,000 richer–their honorarium. Devotees were spiritually enriched. The spectacle’s sheer scale focused needed light on the bedarkened prospects of today’s priesthood. Surely, Vedic rishis would have wanted their sacred ways thus practiced and perpetuated.

What can those who were not there do? At the local level, every Hindu should look into the priests’ situation and work to see they are better paid, properly treated and reinspired to guide their children in the sacred profession. This problem should be discussed at all international Hindu conferences, and global strategies formulated to solve it. If more priests perform such empowering rituals with such mindful proficiency, all mankind may prosper in the worlds seen and unseen.

SRINGERI SADHANA CENTER, RD 8, BOX 8116, STROUDSBURG, PENNSYLVANIA 18360 USA