THE HINDU DIASPORA WITHIN

CONTINENTAL EUROPE

SPECIAL FEATURE

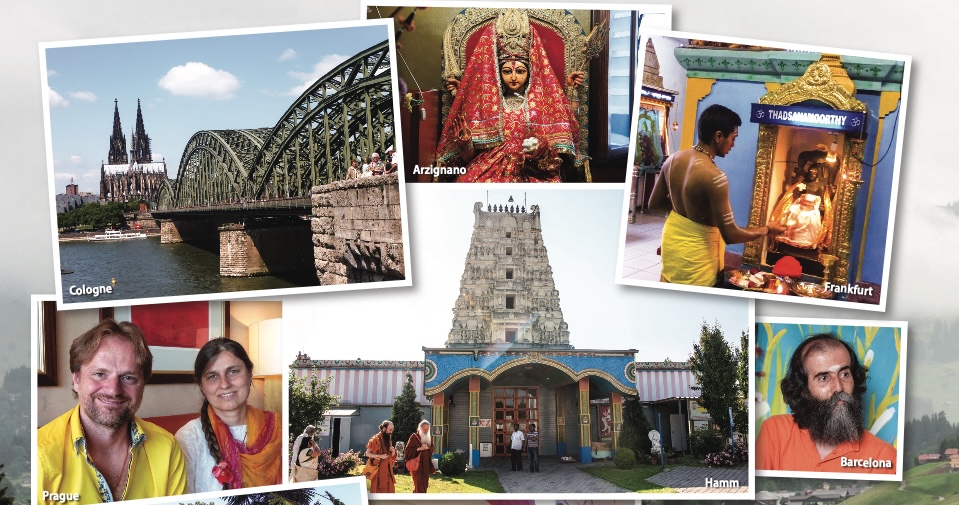

Hinduism Finds a New Home in the Old World

TWO OF OUR EDITORS FROM HAWAII AND OUR UK correspondent visited Portugal, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and the Czech Republic last summer. Interviewing and photographing Hindus who hail from all around the globe, we sought to fill a long-standing gap in HINDUISM TODAY’S coverage of the diaspora: Continental Europe. Unlike in the United Kingdom, Sanatana Dharma’s presence in mainland Europe is still incipient and as varied as the immigrants’ origins. Here, like everywhere Hindus settle, we are preserving our rituals, culture and traditions, building temples, seeking legal recognition of our religion and confronting the perennial challenge of passing our faith on to the next generation.

A RELIGION WITHOUT BORDERS

______________________

Hinduism adds another color to Continental Europe’s religious rainbow

______________________

WHEN ONE THINKS OF THE HINDU diaspora, one typically thinks of people from the Indian subcontinent. But this is a simplistic concept that belies the worldwide distribution of our faith today. In traveling through nine European nations, we found that more Hindus had come from outside India than from within. The Hindu diaspora here seems as varied as the Continent’s own peoples: those we spoke to hail from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Suriname. Adding the tens of thousands of individuals of local European ancestry who find their spiritual home in Sanatana Dharma, a more accurate picture of Hinduism in Europe begins to form.

To compose a comprehensive story of Hinduism in Europe would be impossible after only two weeks in the region, but through the lens of the 38 groups and individuals we encountered, we can assemble an overview of the growing presence of Hinduism in these historic lands and give a sense of the communities, ashrams and satsangs that are setting down roots. As you will see, they come from diverse nations and for different reasons, but they are all bringing the sounds, tastes and colors of Sanatana Dharma to Europe. It’s a story that has never been told.

Kirit Kumar Bachu, president of the Templo Hindu Radha Krishna in Lisbon, Portugal

Portugal

Portugal’s Gujarati community came from Mozambique, where they had lived since the late 1800s. “We’ve been in Mozambique for more than four generations. My father was born there, I was born there, and my daughter was born there,” offered Kirit Kumar Bachu of the Templo Hindu Radha Krishna in Lisbon. But when civil conflict disrupted their country following its independence from Portugal in 1975, they fled. “We chose Portugal because our language was Portuguese. Few of us knew English.”

Portugal’s Hindu community once numbered 10,000-12,000, mostly in Lisbon and the nearby dormitory city of Santo António dos Cavaleiros, with another few hundred in Porto, farther north. Due to the country’s recent economic woes, almost half of them have now migrated to the UK, Brazil, even back to Mozambique, Angola and elsewhere, in search of better opportunities.

Representatives of five Hindu communities and organizations are gathered by Swami Satyananda Saraswati (second from left) in a student’s flat in Barcelona, Spain

Spain

Krishna Kripa Dasa was born Juan Carlos Ramchandani to a Hindu father and Catholic mother. As a young man, he received ordination as a purohit and now performs samskaras for his fellow Sindhis and other Hindu Spaniards. He estimates that some 25,000 of Spain’s 40,000 Hindus have come from India, 5,000 are natives of Eastern Europe (Russia, Ukraine, Poland) and Latin America (Ecuador, Argentina), and 10,000 are Spanish.

Starting in the early 20th century, Sindhis came to the British colony of Gibraltar looking for greater financial opportunity. “From there they went to Ceuta and Melilla, Spanish territories in North Africa, eventually branching out to other cities and islands,” added Krishna. Today this group is concentrated mostly in the Canary Islands, with some around Madrid.

The turn of the millennium brought another wave from India, this time mostly Punjabis, who have settled around Barcelona. The country is also home to small communities of Hindus from Nepal (around 200) and Bangladesh (around 500).

Italy

Svamini Hamsananda Giri, Vice President of the Italian Hindu Union, told us there are roughly 109,000 Hindus in Italy, spread all over the peninsula. Our whirlwind tour afforded us the opportunity to visit just a handful of communities in the industry-dominated northern regions and one on the southern island of Sicily.

Kumar Pradeep, president of the Sanatan Dharm Mandir in Arzignano, shared that his area is home to 10,000 Punjabis—Sikhs as well as Hindus—and 300-400 Bangladeshi Hindus. “Between 1990 and 2000, there was a lot of work here, in marble, wood, plastic, and leather for shoes,” he explained.

A representative of the Shri Hari Om Mandir in Pegognaga added that among the 4,000-5,000 Hindus in his area, 90 percent of whom are from Punjab, 70 percent or more are industrial workers, many at the Landini tractor factory across the Po River. In the bucolic village of Castelverde, a representative of the Shree Durgiana Mandir told us fully one-sixth of the village’s 6,000 people are Indians.

Kumar Pradeep, president of the Sanatan Dharm Mandir in Arzignano, Vicenza, Italy

Those who came to Italy did so only after failing to attain permanent status in other countries, such as France, Germany and Spain. Though language was a hurdle, “Italy was finally the country that granted them legal documentation to stay,” Hamsananda noted. Early on, those who stayed for ten years were able to become citizens, but that door is now closed. “All of the services provided by the government—health, school, welfare—are fully available, but nowadays it is difficult to maintain a visa, even if one has work and family here,” added Hamsananda. Even so, many plan to stay, because they own their homes, hold permanent jobs and their children were born and raised here.

Dhunesshwursing Audit came from Mauritius to Sicily in the early 1990s with 2,500 others, now constituting about a quarter of the Hindus on the island. “We intended to come here to work for 2-5 years at the most. But time has passed so quickly,” he lamented.

Unlike the small numbers of professionals who come from India to Italy to work for two to five years and then return, these communities of immigrant industrial and domestic workers are struggling to stay afloat. As in all the Southern European countries, the economic depression is hitting the community hard, sparking an exodus. Many have left in recent years, and more are on their way, heading to countries such as the UK, Germany, Australia and New Zealand—sometimes back whence they came—in search of newer, better opportunities.

Switzerland

This country’s 40,000 Tamil Hindu refugees fled Sri Lanka’s 26-year civil war that began in 1983. According to V. Ramalingam, manager of the Sri Manonmani Ampal Alayam in Trimbach, Switzerland’s foreign ministry opened its doors to Sri Lankan refugees after its secretary visited the war zone early on and experienced the atrocities first hand.

Due to the language barrier, most of these refugees work in hotels and restaurants or clean factories and houses. They make reasonable, consistent wages, and many homes have two earners, so Switzerland’s high cost of living doesn’t appear to be a problem, explained Dr. Satish Joshi of the Zurich Forum of Religions. “But,” he continued, “even after ten or fifteen years they cannot converse freely in Swiss German or make many friends here. So that makes them hold together as a community.”

Another 10,000 Indian Hindus who call Switzerland home include many Bengalis and recently Malayalis, added Dr. Joshi. “In the last 20 years, many of the Hindu immigrants are IT experts, and many of those are Marathis. They came from India, the UK or the USA intending to stay just six months to a year. But I have observed that many of them remain, preferring the quality of life here to that in England or America.”

ALL PHOTOS: HINDUISM TODAY

Members of the Catania Geetanjali Circle, immigrants from the small Indian Ocean nation of Mauritius, at their Doorga Maa Mandir on the ground floor of a historical building in Catania, Sicily, Italy; Dr. Satish Joshi of the Zurich Forum of Religions, spoke with us at the Omkarananda Ashram in Winterthur, Switzerland

Germany

Owing to its size, stability and productive economy, Germany has attracted one of the largest Hindu populations of all of Europe. Writing for Harvard’s Pluralism Project, Dr. Martin Baumann of the University of Lucerne explained, “We reckon the figure [of Hindus in Germany] to be about 100,000 people, nine-tenths constituted by immigrants who came as workers and refugees.” Mr. Krishnamurthy, who came from Bangalore to Berlin as a welding technician in 1975, reflected on the group that started the city’s Sri Ganesha Tempel: “We all came as technical assistants. We trained and studied in India, and they told us Germany was looking for skilled workers. They offered for us to come for two years to work and then go back. Almost 40 years later, we are still here.” Their story echoes that of many Indian immigrants.

As in Switzerland, Germany’s Indian Hindus are nearly all professionals, and the Sri Lankan refugees, of whom Baumann estimates 45,000 are Hindu, make their way in manual labor—restaurants, factories, houses. At the Sri Sithivinayakar Tempel in Hamm, we met young people of the second generation who are bankers, nurses, teachers, doctors and engineers.

The Sri Lankan Hindus here are mostly spread throughout the state of North Rhine-Westphalia from Hamm to Cologne, with smaller groups in Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich and Nuremberg. Because the Sri Lankan civil war lasted so long, and conditions there are still unfavorable for Tamils, an estimated three-quarters of this refugee group now hold German passports.

Another significant group came from Afghanistan. Their lives in danger because of their religion, they escaped their home reluctantly during the country’s civil war. Germany was one of many countries to extend a helping hand, granting them refugee status. Children came first; parents followed. Representatives of the community’s Hari Om Mandir in Cologne estimated their national numbers at 15,000, concentrated in that area as well as Hamburg and Frankfurt.

According to Luh Gede Juli Wirahmini Bisterfeld of Nyama Braya Bali in Hamburg, the Indonesian Consulate lists 700 Balinese families living in Germany. Unlike the refugees from Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, these freely travel back and forth between Germany and Bali. In explanation, Bisterfeld revealed the sense of obligation they have to their original home: “Besides believing in God, we also believe in our ancestors. We want to go back and take care of our family temples. I think that’s why we seek always to go home.” While a handful are professionals, most Balinese immigrants work in the food service and tourist industries.

Other Hindus have come here from Nepal, the former Hindu kingdom. Ram Pratap Thapa, Consul General of Nepal in Cologne, remarked, “The Nepalese diaspora started in large numbers around 25 years ago. When I came here 30 years ago, there were hardly 50 or 100 people from my country. The statistics are fluctuating, but we see 8,000-10,000 in Germany now.” Many came seeking political asylum, fleeing persecution from the Maoists, and now live in Munich, Berlin, Hamburg, Goettingen and Cologne.

Members of Cologne’s Balinese community listen in during our interview; Mr. Krishnamurthy, founder of the Sri Ganesha Tempel in Berlin.

The Netherlands

One of the largest Hindu populations we encountered on the Continent is in the Netherlands. Bikram Lalbahadoersing, head of Hindu chaplains for the Ministry of Security and Justice, explained, “About 200,000 Hindus are living here in Holland. The biggest group came during the independence period of Suriname [in 1974-75].” About half of Suriname’s population, including some 100,000 Hindus, fled to Holland because of the expected political disturbance.

These Hindus’ ancestors had reached Suriname in the 1800s, when Holland had started importing laborers to that colony after slavery was abolished in 1863, “The Dutch government got permission from the British government to get people mostly from the northern parts of India: Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The language we speak, Bhojpuri, is from Bihar,” added Lalbahadoersing. A century later, when it was time to move again, most came to the Netherlands because they were already Dutch citizens.

Welcomed with open arms, Suriname’s Hindus spent the following four decades reconstructing many of their cultural structures in their new land—everything from mandirs to media to primary schools. They have thrived here, doubling their initial numbers. Lalbahadoersing amplified, “Hindus are very highly educated here in this country. About 30-40 percent go to the universities, especially the ladies.” In the 1980s, the low-lying nation saw a few thousand migrate directly from India as well, mostly professionals.

Austria

Mukundrabhai Joshi, founder of the Hindu Mandir Organization in Vienna, put the unofficial number of Hindus in his country at 11,000-12,000, while lamenting that the official number according to the 2001 census is around 4,000. He explained at least part of the disparity: “Hinduism is not a fully recognized religion here. When a Hindu child is born, the officer will not write ‘Hindu’ as the child’s religion on the birth certificate.”

Joshi said that while some of the Hindus work in the city’s prominent United Nations office, others are businessmen, university students, clothing and newspaper vendors. Dr. Bimal Kundu, a pharmacist who founded a small temple in the Afro-Asian Institute in Vienna, opined that many of Vienna’s Hindu trade workers and businessman are Punjabi, and that substantial Nepalese and Bangladeshi communities have recently arrived.

Czech Republic

The Czech Hindu Religious Society has a membership of 10,000, according to its representative, Vivek Ojha. Of these, not all are active. “When we organize functions in Prague, we have 300-350 people,” he added. “Most of our followers are educated; they are intellectuals, doctors, engineers. Also, the lower middle class, the service class—they know about Hindu culture and religion, yoga and vegetarianism. Those who feel it is for them have joined the Society as well.”

Where have these Czech Hindus come from? Surprisingly, over 99 percent of the Society’s members are local Czech people who declare themselves to be Hindu. Less than one percent are immigrants, coming from India, Bangladesh and Nepal.

ALL PHOTOS: NIRAJ THAKER

Bikram Lalbahadoersing, head of Hindu chaplains for the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice; Satyapuri Vit Levy and Sanjivni Iva Levy of the Czech Friends of India Association and Vivek Ojha and Anandapuri Andras Sukub of the Czech Hindu Religious Society.

France

The largest Hindu population we found is in France. “There is a big Hindu community in and around Paris. Most of them have come from Pondicherry, which was a French colony,” offered Swami Veetamohananda of the Centre Védantique in Gretz-Armainvilliers. France also has communities hailing from Mauritius, Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana and Reunion, whose backgrounds and stories closely parallel those of the Surinamese immigrants to the Netherlands.

The number of Sri Lankan Tamil refugees in France is uncertain, but Mr. Jeyaratnam, manager of Paris’s prominent Ganesh Temple—himself an immigrant from Sri Lanka—estimated there are 300,000-400,000, with more than 200,000 in the greater Paris area alone. Most came as refugees, many at the start of Sri Lanka’s civil war in the early 1980s and others trickling in later. Jeyaratnam explained, “Many were in other places all over Europe, and when they learned it would be easy for them in Paris, they came right in and spread throughout the area.” In France they could receive social security, health care and other government services.

Rajat Rai, a representative of the Bangladesh Pooja Udjapan Parishad, came to France in 1991 to escape minority persecution in Bangladesh. He told us 1,500 families in his community live in Paris. “But language is a difficulty here. Bangladesh was a British colony, and our second language is English. At first I couldn’t even say that I needed a glass of water. We all struggled with this.” He even left France for a time due to this frustration. “Now I speak a little French, so everything is easy, but if you can’t speak French, it’s very difficult.”

Like the Mauritian Italians, Sri Lankan Swiss, Afghan and Nepali Germans and others who had fled economic or political hardship, these immigrants had no choice but to adopt menial occupations. Their professional degrees—in medicine, architecture, science, engineering, etc.—from their home country were not recognized in their new land. Combined with the language barrier, this significantly limits their vocational opportunities. However, the outlook is far better for the second generation. Born in Europe, fluent in their new country’s language and locally educated, with the advantage of a religious tradition that emphasizes study, personal effort and self-improvement, they are thriving.