By M.P. MOHANTY, NEW DELHI

For untold centuries in india, it had been routinely regarded as immoral to neglect the needs of one’s elders. In 1996, it became clearly illegal. The passing of the Maintenance of Parents and Dependents Bill of Himachal Pradesh attempts to insure proper care for anyone who is dependent upon another. It has raised significant concern over the care of India’s aged, but it also applies to children, wives and widows [see page 25]. The passing of such a law in Himachal Pradesh, a small hill state known for the culture of its peace-loving, religious people, has greatly shaken the conscience of thoughtful observers of Indian society. Hindus around the world are inquiring, “Why do we need a law to make us care for our elders? Are they not attended to by their families?”

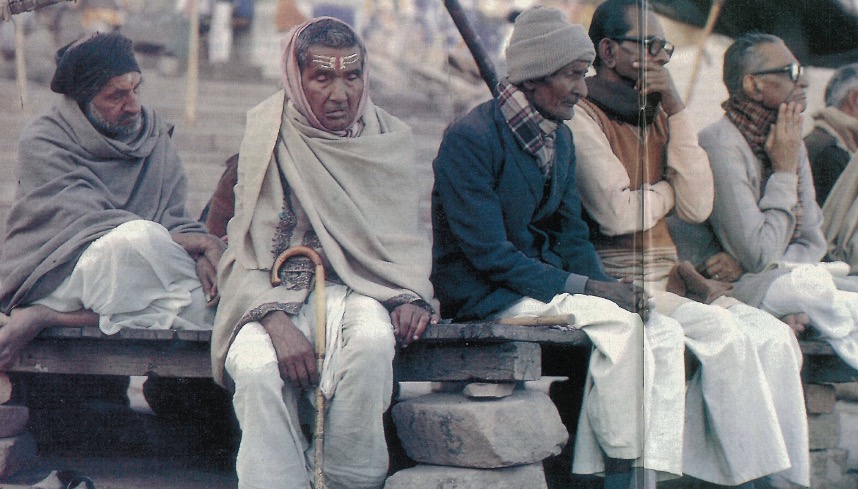

Mr. Pran Nath Malik, 70, a retired government servant now living in Delhi, gives an ominous answer–“No. The population of old people here is in the tens of millions. As about half of our total population are living below the poverty line, most of the aged poor are merely existing, without proper food, shelter or medical care. The assistance provided by the government is negligible. Social and religious organizations also are not doing much. We can see many elderly living as beggars in the big cities. Many die of hunger.”

Those who do not starve to death may die of loneliness. The tales of dereliction are bone-chillingly cruel. Hinduism Today writer Shikha Malaviya of Minnesota recounted one example upon her recent return to the US from India. “For some people, old age means shouldering a burden. Take the case of the Miglanis (not their real name), a Hindu family in New Delhi living next to my uncle. From the outside, they appear to be an honest, caring and religious family. A plaque of Lord Krishna playing the flute above the main entrance of their home greets visitors. Inside, however, lies a different story. For more than two years, Mr. Miglani’s father lived in a makeshift room with a tin roof on the back verandah. He was not allowed in the main house and was verbally abused constantly by his children and grandchildren. Mr. Miglani Sr. was ill, but did not receive proper treatment and eventually died of neglect in the summer of 1995.”

Malaviya says the elderly, and often their children, take illness too lightly, and go much too long before diagnosis or treatment. “My grandmother has a heart condition called angina. She also has gastric trouble. For one month she had palpitations, fever and painful gas attacks, but she didn’t go to the hospital until four days ago. She shares the attitude, like many others do in India, that ‘it isn’t bad until it’s really bad.’ The cost of healthcare inhibits many from getting regular checkups, let alone treatment for ailments.”

Another grim account of callousness comes from Delhi businessman Govind Chandra Rout. He confessed that, “Even in our Orissan village, yes, in my own family, old people are being neglected. The old mother of my cousin has been left in the village alone. She is begging. There are thousands of such examples. Sons beat their old parents, even the educated ones. I do not want to name them or blame them. I tell you a fact: one son refused to recognize his poor, old father when his father came to school to meet him. The old father died unattended. This same son later retired as a senior government official. When he died, both of his own sons, staying in Bombay and the US, failed to come and perform the funeral rites. You can see, this was the result of his karma.”

Rout recalls and keeps alive the way it used to be. “As children, we learned that our father is the Adi Guru, first teacher, and I still impart these Hindu values to my grandchildren. The doors of our home are always open for saints. Every morning and evening we assemble and pray to Lord. I tell them to be truthful and religious. This way of living must be taught in schools at the primary level. We must preserve our great heritage. Unfortunately, today’s generation believes they know it all, and better than us.”

The symptoms of neglect are usually less tragic, but they clearly indicate the change in ethos that seems to have infected the nation. This reporter recalls an incident at a friend’s place. Grandmother had wanted to watch a classical music concert, while the grandson was eager for the latest pop news on Zee TV, a private television channel. In walks the father, who settled the argument by scolding his mother, “Why don’t you let him watch his rock show? You can catch another concert when we are not here.” The old woman walked away in a huff. It is a revealing incident, and it is all too common.

Ajay Sunder of HelpAge, India, the most active Indian charity for the elderly, explains a primary source of distress for seniors. “For the senescent in the upper and middle classes, the problems are loneliness and depression. If these problems remain unaddressed, they intensify into bitterness and a feeling of being unwanted, especially in the really old. For those in the age bracket of 60 to 70 the solution can lie in involving themselves with volunteer work or any activity in the neighborhood. But the problem becomes intense for those beyond 70 or 75.”

Raji Narasimhan, 68, finds herself regretful ten years after the death of her parents-in-law. Both of her sons are away in the US, and her only daughter struggles with a busy career and a demanding family, with little time for Raji. Between loneliness and boredom, Raji recalls her in-laws’ predicament. “Now I wish I had spent more time with them and not lost my temper so often. They only needed a little understanding, patience and reassurance that they were cherished.” Remorseful, she realizes how concrete their contribution to the family was. “I never had to worry about what my children were doing after school. And on occasions such as weddings, they were always there to guide us.”

No time, no place: All fingers point to the breakdown of the joint family tradition [“Joint Family at Risk,” January, 1997] as the root cause of neglect. Concern over the dissolution of this social order, along with the rising presence of women in the workplace, has primarily focused on children growing up without mothers at their side. But the elderly are equally dependent and vulnerable. “The ideal situation is, of course, caring for the aged in their own homes,” offers Sunder. “But for many, attending to aged people seems a tedious, time-consuming and often unproductive affair. Given the pressures of managing a home, careers and the conflicting needs of children and old people, it is the elders in the family who are expected to adjust to the youngers’ needs while their own take a back seat.” One analyst observed that “The breakdown commenced when the maharajas, India’s regional kings, were deposed. Until then, these monarchs and their families modulated society and kept the joint and extended family structure intact.”

What has resulted is a distorted attitude toward the aged. Social activist and educator Rekha Vohra Bhalla implores, “Do we not realize how lonely they are? They do not require luxury. What they seek is love, affection and company. They want their children to be with them in the evening of life, to provide warmth and comfort them. The whole concept of age-care in India is an ancient part of our civilization, whereas ageing as a problem is a product of modern India. Earlier, old people were taken care of within the joint family. Our culture and ethics taught us not to neglect them. We were morally bound to take care of them. Our value system has changed. This is the real problem.”

Hari Bilas, whom I met at a traffic light, drove home this point. He looked like a mendicant, yet he insisted, “I am not a beggar. I have my elder brother and his family, and the government of Rajasthan pays me Rs.100 a month. But I have chronic asthma, and I need tea and medicine at regular intervals, including two-to-three times during the night. At home, they feel disturbed to assist me. So I stay here on the footpaths. I cannot afford an old-age home. Life is misery. I certainly feel marginalized and discriminated against, and it saddens me, this lack of respect towards us, the poor and old. It was not this way in our times. We looked up to elders, respected their experience and knowledge and learned from them.”

The modern Indian family has left the elders behind. “We have divided our families based on economy,” Bhalla elaborated. “The middle-class is moving to cities in search of opportunities, leaving old parents in rural areas. At least there, neighbors, friends and other relatives do take care. But in cities it is very difficult. Rents are so high that we can afford only small flats or apartments. So, we claim that due to lack of space and monetary considerations parents cannot be accommodated. Actually, space is not the real problem, not even the financial burden, but we do not have an honest approach. We have become small-hearted due to modernization.”

Gift buys grief: One way seniors are left in the lurch is in the transfer of estates and assets to their children. In the West, this transaction usually takes place after death through a legal will. In India, it has been common to legally transfer such properties and accounts long before death. When performed ethically, this practice frees the elder of the burden of property and money management so that he may better advise his children and intensify his spiritual disciplines–the natural functions of this stage of life. It is rightfully understood that the children would continue to care for the parent. But in an inhuman twist, once the transfer is made, sons may completely neglect the parents, sometimes even ejecting them from the home. A retired Indian administrative officer has been forced to spend the last few years of his life in an old-age home. Indignant, he explained that he had transferred his assets to his son. While the mother has been allowed to stay at home as a glorified maid, he was bundled off to this pay-and-stay home. His son claims the rented apartment in which they live is too small to accommodate all of them.

H.C. Bakshi, Former Joint Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Office, cautions parents to be wary of this trap. “Old people must have independent financial support. While living, you should not transfer property to your son, but make a will. Children should inherit the property only after death. Without financial support, you are a loser. I know of a case in Patel Nagar, Delhi, where the retired person transferred his property while living. Afterwards, he was treated as a virtual slave. He was moved against his will to a small room on the roof. Later, he was dumped into the garage.”

Even lawmakers were alert to this familial flimflam. Section 18.1 of the Himachal Pradesh Bill states, “Where any person, who after the commencement of this Act, has transferred, by way of gift or otherwise, his property, subject to the condition that the transferee shall provide the basic amenities, and basic physical needs to the transferrer and such transferee refuses or fails to provide such amenities and physical needs, the said transfer of the property shall be deemed to have been made by fraud or coercion or under undue influence and shall at the option of the transferrer be void.”

Who will help? “This problem must be handled,” beseeches Bhalla. “Tomorrow we will grow old. We have to shock ourselves with the reality that our children might put us in old-age homes, uncared for. Are we preparing for such a future?” India today has nearly 60 million elderly people, and demographic projections forecast 75 million by the year 2000. Yet assistance for the aged has been a low priority among the various welfare schemes being implemented by the government and voluntary agencies. Critics concede that the government simply does not have the resources to effect a significant change.

Most governmental and private agencies and persons engaged in care of seniors think that the malaise of poverty among the multitude of elderly can only be offset if significant funds are made available for implementing welfare programs–homes for the aged, eye-care, walkers and other handicapped aids, day-care, health-care, mobile medicare vans, etc. Current programs concentrate in cities and towns and do not impact people in rural areas. Bakshi concludes, “This is a tremendous crisis that can be solved only by public-spirited individuals and institutions.”

HelpAge deputy director Limaye admits that rest homes are a secondary choice. “Our programs work towards resettling them within their families. But when their children are abroad or no one is there to look after them, they can resort to this option.” A primary source of fundraising for HelpAge is the sale of greeting cards, and many Indians become aware of the plight of India’s elderly through HelpAge cards. They even gave me a shock. Out of the total one-hundred and eleven new year’s greeting cards that I received this year, sixty-two are HelpAge cards. On the back of each card reads, “The less privileged elderly need your love and care. When you buy this card you contribute to making their world healthier and happier.” HelpAge is leading the way, but many more need to follow.

The way it was: Of course, not every elder is forsaken. For Jayanti Nair, looking after her ailing parents and in-laws was never a matter of choice. “They looked after us,” she admonishes. “We were young and needed them. So we will jolly-well look after them in return. They are part of our life.”

“It is important to remember that old age in our religion is associated with the sannyas ashrama (stage of renouncing materialism and attachment to embrace God and spirituality), and that old age is a stage of spiritual evolution,” stresses Malaviya. “Old age doesn’t mean gray hair, stiff joints and slurred speech. There are volumes we can learn from the wisdom they have culled from their own successes and failures. Growing old is an inevitable physical and mental transition that doesn’t have to be painful or debilitating. We need to accommodate the needs of elders without their asking, and we can’t do that until we understand what aging is all about.”

M.C. Bhandari, president of Bharat Nirman (Build India) and editor of Mystic India, echos the ideal for elders, “Our scriptures state that whatever thought that you have in the last moments influences your next birth. One should die with positive, noble and spiritual thoughts. Old people should bellow the path of dharma. They have the full experience of life. They are society’s thought-bank. They should educate the younger generations from day one, tell their experiences–how they feel at this age. It will help them in this life, and improve the next.”

Legislature does not automatically make a society good and caring. And though passing a law is relatively simple, the efficacy of implementation and enforcement remains to be seen. At least the verdict for this negligency case has been handed down–“Guilty.” Where the softer versions of law–the natural justice of our cultural expectations–seem to have failed, it now requires courts for elderly care to be enforced.

helpage india, c-14, qutab institutional area, new delhi 110016 india. phone: 91-11-686-5675

SIDEBAR: IT’S THE LAW

The bill that dares to arrest neglect.

Himachal pradesh’s Maintenance of Parents and Dependents Bill (number 29 of 1996) paints a bleak picture of the care of India’s elderly. On the last page of the bill, Minister-in-Charge, Vidya Dhar, gives a Statement of Objectives and Reasons: “In the developing age of science and technology, our old virtues are giving way to materialistic and separatistic tendencies. The younger generation are neglecting their wives, children and aged and infirm parents, who are now being left beggared and destitute on the scrap-heap of society, thereby driven to a life of vagrancy, immorality and crime for their subsistence. Thus it has become necessary to provide compassionate and speedy remedy to ameliorate the difficulties being faced by those so neglected.”

The bill is not limited to protection of the elderly. It encompasses, with stipulations, parents and grandparents, wives, sons, unmarried daughters, widowed daughters, any widow of the son, minor illegitimate sons and illegitimate daughters.

The government will form tribunals as needed in each district to deliberate applications. Section 3.1 of the bill clarifies, “Any person, who is unable to maintain himself and is resident in the State of Himachal Pradesh, may apply to the Tribunal for an order that [the responsible party] pay a monthly allowance, or any other periodical payment or a lump sum for his maintenance.” Depending on who is applying, the person held responsible for maintenance may be the children or grand-children, the husband, the father, and where father is dead, the mother, or the person who takes any share in an estate of the ancestor.

Section 3.4 defines the broad criteria of maintenance eligibility. “This Act shall apply to that person if the Tribunal is satisfied that he is suffering from infirmity of mind or body which prevents or makes it difficult for him to maintain himself or that there is any other special reason.” The Bill continues with a definition of what constitutes need. “A parent is unable to maintain himself if his total or expected income and other financial resources are inadequate to provide basic amenities and basic physical needs including (but not limited to) shelter, food and clothing.”

Vidya Dhar states in his conclusion, “In our society, the maintenance of aged parents had been a matter of great concern and of personal obligation. Our ancient seers held this obligation on the highest pedestal by declaring that, ‘The aged mother and father, the chaste wife and infant child must be maintained, even at great cost.’ This Bill seeks to achieve the aforesaid objectives.”