Following his profitable conquest of Karnataka, Kerala and northern Sri Lanka, the Tamil King Rajaraja Chola found himself with a considerable budget surplus. With vast tracts of fertile farmland already under year-round irrigation, he decided to build the largest Siva temple in the world, Brihadisvara, at Thanjavur (Tanjore in modern Tamil Nadu state), a stunning masterpiece of stonecraft engineering. The temple, now on the United Nations World Heritage List, was crowned in the king’s vision. He capped the 216-foot main sanctum with a single stone weighing 86 tons and set in place by elephants’ nudging it up a gentle sand ramp starting five miles away. The great sthapati (architect and sculptor) Kunjara Mallan Raja Raja Perunthachan was commissioned for the work.

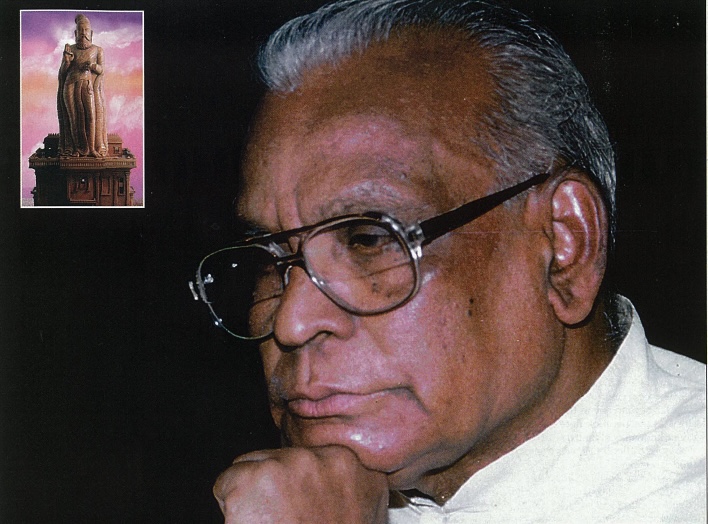

That’s a story that Dr. Vaidyanathan Ganapati Sthapati, 72, loves to hear, for he is a lineal descendent of that same Perunthachan of a thousand years ago. The great man’s story reminds Ganapati Sthapati today of the tradition he is commissioned by birth to uphold. and of the indomitable spirit of his caste, the silpis, lords and masters of South India’s hard and heavy granite.

Though trained in stonecraft as a boy by his father and uncle, Ganapati Sthapati initially embarked on a career teaching mathematics. But as the great poet Valluvar said, “What destiny calls yours will not depart.” In 1957 Ganapati Sthapati joined the Tamil Nadu government temple board and began overseeing temple designs and construction.

In 1961 he took over as principal of the Government College of Architecture and Sculpture, Mamallapuram, which his father and other sthapatis founded just four years earlier to issue degrees in affiliation with the University of Madras. For 27 years, until retiring in 1988, Ganapati Sthapati meticulously trained three generations of temple architects, sculptors and carvers. He taught them, too, the profound mystical side of the silpi tradition, how to create not just sculptures, but the very body of God. During his tenure, he oversaw the construction of dozens of temples, the carving of thousands of sculptures and even the construction of a few secular buildings, such as the library and administrative offices of the Tamil University in Tanjore.

Retirement for Sthapati hardly meant extra leisure. Rather than rest, he launched a private practice and was commissioned to build temples not only in India, but everywhere Hindus had settled in the past few decades. He has completed temples in America, England, Singapore, Malaysia, Fiji, Sri Lanka and Canada. Accomplished artist, sculptor, designer and project manager that he is, Ganapati Sthapati also succeeded at a broader and more meaningful goal: to establish India’s ancient construction arts as an important and useful field of knowledge in the 21st century. In the process, he has evaluated each aspect of the ancient art in terms of modern methods. The silpis, for example, use simple iron chisels made and maintained by onsite blacksmiths. Sthapati experimented with various metals to replace these iron tools, but ultimately found none an improvement over the traditional, cheap and easily created iron ones. As an alternate to breaking out stones with hand-methods, he tried blasting them lose with dynamite. But stones so quarried, he discovered, “lost their tone,” and were useless for sculpting.

Noticing the trend toward simpler and simpler sculptures, Sthapati brought back clever and delicate demonstrations of the stone carver’s art, such as the remarkable stone bell on a stone chain, with a stone clapper–all carved from a single rock.

Perhaps closest to Sthapati’s heart has been exploring the philosophical, theoretical and historical traditions of stone carving. It is a field of knowledge that encompasses all dimensions of architecture, from sculpture design to town planning. In the process, he has generated renewed interest in the Vastu Shastras, the scriptures of this art, which he is having translated into English from the their original Sanskrit or ancient Tamil. Intrigued by the possible relationship between Maya, the Godly architect in Hindu tradition, and the Mayan people of South and Central America, he traveled throughout that region visiting ancient monuments and meeting with modern Mayan representatives. Repeatedly he was astounded by similarities between Hindu construction design and that of the Mayans, right down to the use of the same measurements and proportions. No explanation has been offered as to how this occurred, as the two peoples were never known to have been in contact.

Throughout his life, Sthapati has worked to revitalize an ancient art imperiled by technology’s usurpation of the hand-crafted way of life and its deeply spiritual and aesthetic principles.

V. Ganapati Sthapati, Vastu Vedic Research

Foundation, Plot No. S46, First Avenue, Vettuvankeni,

Enjambakkam Village, Chennai 600 048Iindia.

email: vastuved@md3.vsnl.net.in