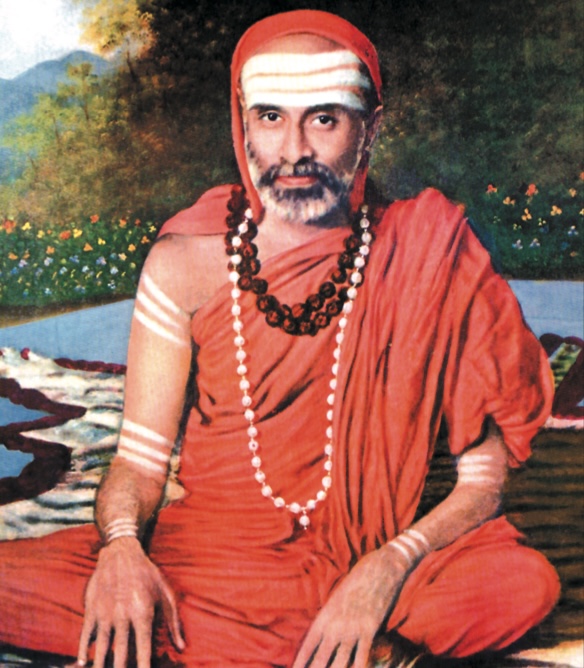

His Holiness Sri Chandrashekara Bharati Mahaswami, 1892-1954, was the Sankaracharya of Sringeri Peetha for 42 years. He was a learned and articulate expositor of the Advaita Vedanta philosophy of the Smarta denomination of Hinduism. We share with you some of his trenchant insights into the mysteries of free will and fate, excerpted from dialogs with a disciple.

Devotee (D): One doubt repeatedly comes up during my Vedanta studies, and that is the problem of the eternal conflict between fate and free will.

His Holiness (HH): A conflict arises only if there are two things. As a follower of our Sanatana Dharma, you must know that fate is nothing extraneous to yourself, but only the sum total of the results of your past actions. As God is but the dispenser of the fruits of actions, fate, those fruits are not his creation, only yours. Free will is what you exercise when you act now. Fate is past karma; free will is present karma. Both are really one, that is, karma, though they may differ in the matter of time. There can be no conflict when they are really one.

D: But the difference in time is a vital difference which we cannot overlook.

HH: I do not want you to overlook it, but only to study it more deeply. The present is before you and, by the exercise of free will, you can attempt to shape it. The past is past and is therefore beyond your vision and is rightly called adrishta, the unseen. How do you expect to find a solution to the problem of fate and free will when the former by its very nature is unseen! It is profitless to embark on the enquiry as to the relative strength of fate and free will.

D: Does your Holiness then mean to say that we must resign ourselves to fate?

HH: Certainly not. On the other hand, you must devote yourself to free will. By exercising your free will in the past, you brought on the resultant fate. By exercising your free will in the present, I want you to wipe out your past record if it hurts you, or to add to it if you find it enjoyable. In any case, whether to acquire more happiness or to reduce misery, you have to exercise your free will in the present.

D: But the exercise of free will, however well directed, very often fails to secure the desired result, as fate steps in and nullifies the action of free will.

HH: You are again ignoring our definition of fate. It is not an extraneous new thing which steps in to nullify your free will. On the other hand, it is already in yourself.

D: It may be so, but its existence is felt only when it comes into conflict with free will. How can we possibly wipe out the past record when we do not know or have the means of knowing what it is?

HH: Except to a few highly advanced souls, the past remains unknown. But our ignorance of it is advantageous. If we knew all the accumulated results of this and our past lives, we would be so shocked as to give up in despair any attempt to overcome or mitigate them. Forgetfulness is a boon bestowed by the merciful God. Similarly, the divine spark in us is ever bright with hope and makes it possible for us to confidently exercise our free will.

D: All the same, it cannot be denied that fate very often does present a formidable obstacle in the way of such exercise.

HH: It is not quite correct to say that fate places obstacles in the way of free will. By seeming to oppose our efforts, it tells us the extent that free will is necessary now to bear fruit. Ordinarily, to secure a single benefit, a particular activity is prescribed; but we do not know how intensively or how repeatedly to pursue or persist in that activity. If we do not at first succeed, we can deduce that in the past we exercised our free will in the opposite direction, that the result of that past activity must first be eliminated and that our present effort must be proportionate to that past activity. The obstacle which fate seems to offer is just our gauge to guide our present activities.

At the start, do not be obsessed at all with the idea that there will be any obstacles. Start with boundless hope and with the presumption that there is nothing in the way of your exercising the free will. If you do not succeed, tell yourself that there has been in the past a counterinfluence brought on by yourself by exercising your free will in the other direction. Therefore, you must now exercise your free will with redoubled vigor and persistence to achieve your object. Tell yourself that, inasmuch as the seeming obstacle is of your own making, it is certainly within your competence to overcome it. If you do not succeed even after this renewed effort, there can be absolutely no justification for despair, for fate being but a creature of your free will can never be stronger than your free will. Your failure only means that your present exercise of free will is not sufficient to counteract the result of the past exercise of it. There is no question of a relative proportion between fate and free will as distinct factors in life. The relative proportion is only between the intensity of our past action and the intensity of our present action.

D: But even so, the relative intensity can be realized only at the end of our present effort in a particular direction.

HH: It is always so in the case of anything which is adrishta or unseen. For example, the length of a nail embedded in a varnished pillar and the composition of the wood are unseen, or adrishta, so far as you are concerned. The number and intensity of the pulls needed to take out the nail depend upon the number and intensity of the strokes which drove it in. Do we stop from pulling out the nail simply because we are ignorant of its length or of the number and intensity of the strokes which drove it in? Or, do we persist in pulling it out by increasing our effort?

D: Certainly, as practical men we adopt the latter course.

HH: Adopt the same course in every effort of yours. Exert yourself as much as you can. Your will must succeed in the end.

D: But there certainly are many things which are impossible to attain even after the utmost exertion.

HH: There you are mistaken. There is nothing which is really unattainable. A thing, however, may be unattainable to us at the particular stage at which we are, or with the qualifications that we possess. Its attainability is not absolute but is relative and proportionate to our capacity.

D: The success or failure of an effort can be known definitely only at the end. How are we then to know beforehand whether with our present capacity we may or may not exert ourselves to attain a particular object, and whether it is the right kind of exertion for the attainment of that object?

HH: Your question is certainly a pertinent one. The whole aim of our Dharma Shastras is to give a detailed answer to your question. Religion leaves man quite free to act, but tells him at the same time what is good for him and what is not. He cannot escape responsibility by blaming fate, for fate is of his own making, nor by blaming God, for He is but the dispenser of fruits in accordance with the merits of actions. You are the master of your own destiny. It is for you to make it, to better it or to mar it. This is your privilege. This is your responsibility.

D: But often it so happens that I am not really master of myself. I know, for instance, quite well that a particular act is wrong; at the same time, I feel impelled to do it. Similarly, I know that another act is right; at the same time, however, I feel powerless to do it. It seems that there is some power which is able to control or defy my free will. So long as that power is potent, how can I be called the master of my own destiny? What is that power but fate?

HH: Fate is a thing quite different from the other one which you call a power. At first a man steals with great effort and fear; the next time both his effort and fear are less. As opportunities increase, stealing becomes habitual, requiring no effort at all, done even when there is no necessity. This tendency goes by the name vasana. The power which makes you act as if against your will is only the vasana of your own making. This is not fate. The punishment or reward, in the shape of pain or pleasure, which is the inevitable consequence of an act, good or bad, is alone the province of fate or destiny.

The vasana which the doing of an act leaves behind in the mind in the shape of a taste, a greater facility or a greater tendency for doing the same act once again, is quite a different thing. The punishment or the reward of a past act is, in ordinary circumstances, unavoidable, if there is no counter-effort; but the vasana can be easily handled if only we exercise our free will correctly.

D: But the number of vasanas or tendencies that rule our hearts is endless. How can we possibly control them?

HH: A vasana seeks expression in outward acts. This essential characteristic is common to all vasanas, good and bad. The stream of vasanas, the vasana sarit, as it is called, has two currents, the good and the bad. If you try to dam up the entire stream, there may be danger. The shastras, therefore, do not ask you to attempt that. They ask you to be led by the good vasana current and to resist being led away by the bad vasana current. When you know that a particular vasana is rising up in your mind, you cannot possibly say that you are at its mercy. The responsibility to encourage it or not is entirely yours.

The Shastras enunciate what vasanas are good and have to be encouraged and what vasanas have to be overcome. When, by dint of practice, you have made all your vasanas good and practically eliminated the charge of any bad vasanas leading you astray, the shastras teach you how to free your free will even from the need of being led by good vasanas. You will gradually be led on to a stage when your free will be entirely free from any sort of coloring due to any vasanas. At that stage, your mind will be pure as crystal and all motive for particular action will cease to be. Freedom from the results of particular actions is an inevitable consequence. Both fate and vasana disappear. There is freedom for ever more and that freedom is called moksha.