By AJITH BRIDGRAJ

Every major world city has a “Little India” district. But the continent of Africa, apparently accustomed to being grandiose, has an entire “Little India” nation–that is, South Africa. Of all the countries Indians have adopted–once transcending the “imported indentured laborers” stigma–South Africa is by far the most endeared to the Indians who live here. It is similarly revered by Indians in India, as the heroic Mahatma Gandhi had his beginnings here. His first-hand experiences of apartheid in South Africa were critical in forming his satyagraha strategies and mission. And, there is perhaps no other non-Asian country that feels that Indians–and their religion–are such an important and integral part of the nation. Indians are counted as one of the “Big Three” ethnic majorities.

The Durban Experience website (www.durban.org.za/) exemplifies this spirit. A page on the city’s ethnic makeup reads, “If cultural diversity were the criterion for choosing the capital of the new South Africa, then Durban would be the only city in the running. In a country dubbed the Rainbow Nation, this port city is blessed with the most vibrant mix of the ethnic and cultural paint brush. The metropolis is home to three major social groupings, each with its own rich history and traditions. It was the labor of the noble descendants of Shaka’s mighty Zulu Nation which made the city the commercial and industrial hub of the province. Now with the demise of apartheid, they have become the major political force in the region, with members of both the two biggest parties, the ANC and IFP, proud to be called Zulus. The quirks and mannerisms of the British settlers in Natal earned the province its nickname of Last Outpost of the British Empire. Now the great-great-grandchildren of those hardy pioneers consider themselves as South African as their Zulu neighbors.

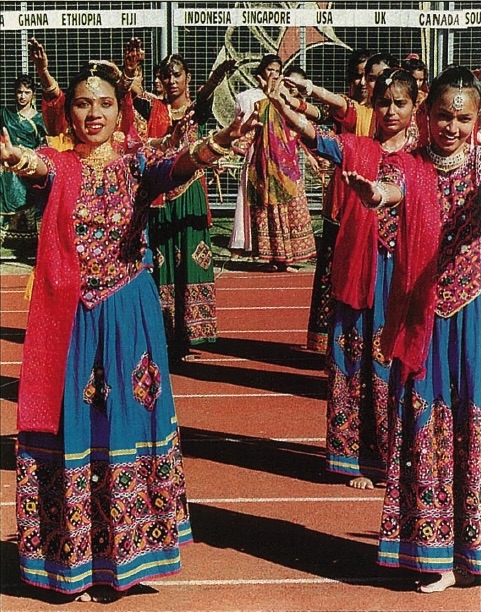

“The forerunners of Durban’s thriving Indian community arrived in Durban as penniless indentured laborers last century. Since then they have built themselves into a force to be reckoned with, in the fields of commerce, culture and politics. Apart from the big three, Durban is also home to people of Dutch, Portuguese and Chinese descent to name only a few. And many of them are second or third generation Durbanites. With such a tapestry as a backdrop, it’s little wonder that the city has such a rich cultural and artistic life. Cultural enthusiasts will be greeted by a kaleidoscope of Indian, Colonial and African traditions that have prospered in the city and given rise to a wide variety of food, restaurants, arts and crafts, and ethnic dance forms.”

It would be difficult to overstress how deeply the traditions of Hindu culture–dance, dress, philosophy, food, etc.–are appreciated by the South African populace and how graciously these contributions are received.

Another page on this website recounts the history of Indians in Durban, and virtually the same tale can be told for each major city in the nation. “From 1849 to 1851, over 4,000 British settlers came to Natal under a scheme which was devised by Joseph Byrne. There were many businessmen among them, and from this time onwards the small village of Durban began to progress. Shortly after this event it was found that sugar was a suitable and profitable crop to grow, and the development was rapid. It was this development which prompted the Province to import laborers from India, and these, in turn, were followed by traders. Today their descendents form a very important part of the Durban citizenry.”

Notwithstanding these civic successes, a thriving Indian community does not a vibrant Hindu religion make, and there are mixed views regarding the vitality of Hinduism in South Africa. Many well-established Hindu organizations prosper here, to be sure, and the religion has a long history, which gives a certain stability. But there exists a high conversion rate away from Hinduism, primarily to Christianity, and a state of spiritual dormancy seems to prevail.

To be, or not to be…Hindu: While speaking with Hinduism Today, Linda Govender, a school teacher in Durban, divulged why she turned away from Hinduism. “I was plagued by a prolonged period of illness, which doctors were unable to cure. But I noticed a slight improvement in my condition after the pastor from the local church began to pray for me. The dynamic youth movement at the church also provided a spiritual and social outlet for my son, something we did not have as Hindus. In fact, I did not even know who the local Hindu priest was when I really needed someone to minister to my needs.”

Other youth corroborate the essence of Govender’s story. Urisha Brijlall, a pupil at the A.D. Lazarus Secondary school, Durban, warns, “Hindus need to be enlightened on the immense depth of their religion and heritage. Unfortunately, many Hindus are exploring new canals of thought and are converting to other religions.” Cassandra Subramony, a 15-year-old classmate of Brijlall complains, “Hinduism is to me the most intriguing, ancient religion, which provides deep insights through its philosophies. But, sadly, I think that many Hindus in South Africa are not practicing these majestic teachings. Many of the youth do not show tolerance and respect for other religions. Many more are unable to speak their mother tongue. Also, if Hindu elders cannot teach their children the basic principles of Hinduism, then many souls will be lost in the world, for where there is no understanding, there will be incorrect action. We are currently witnessing this as teenagers turn to dangerous past-times like alcohol and drug abuse.”

Saraspathi Naidu, age 35, of Phoenix, also converted to Christianity. Her grievances are a clarion call to Hindu leaders: “As a Hindu, I found myself bogged down with ritualistic worship. Most of the time I did not understand why I was doing the things I did. When I inquired, I had to be content with the explanation that those were the way our ancestors had done things. Now, as a Christian, I have a holy book, the Bible, which I can read and understand and which is constantly discussed and analyzed in church. Hindu leaders, however, do not place a high premium on acquainting Hindus with their scriptural works.”

The Hindu chieftains: Conversion concerns are real, but they are not felt to be a dire threat, for the dominant Hindu organizations in South Africa do minister actively to a large number of steadfast devotees. Most encouraging to all is the fact that youth figure prominently–through attendance as well as in conception and organization–in temple functions and the popular yoga camps held by several institutions.

Strict disciplines of meditation and vegetarianism are emphasized by the Divine Life Society (DLS), as well as a ban on watching television. In this way the DLS aims to produce devotees of strong moral fiber. Swami Sahajananda, present head of the DLS, devotes a great deal of energy and attention to children. Yoga camps are a DLS specialty. Apart from ministering to the religious and spiritual needs of devotees, the DLS is deeply committed to community welfare work, including building schools for underprivileged (usually black) communities. Their well-known high-tech printing press facility makes possible in the dissemination of popular religious literature.

The Arya Samaj, too, has firmly nurtured Hindus in South Africa since its inception in 1906. Staunch devotee Pandita Nanackchand, 74, one of the first females inducted into the South African priesthood, became a follower after marriage. “My paternal grandfather came to South Africa with the first indentured Indians in 1860,” she recalls. Her grandfather had become embroiled in a family dispute over property in Benares, and that motivated him to go to South Africa. “Their early life was extremely difficult, as they had to reside in communal barracks and survive on food rations,” says the Pandita.

The Arya Prathinidhi Sabha (APS) is the parent body of the Arya Samaj Movement in South Africa. The Durban Isthri Samaj and the Arya Stree Samaj are women’s adjuncts. Nanackchand belongs to all three, stressing that she emerged from a deeply religious and strong Puranic background and was well schooled in Hindi before she married at the age of 18. In 1971?72, she and five others responded to a call for women to join the priesthood: “In 1975, following the successful completion of examinations, I was given the gown and have been practicing as a priest ever since.” Nanackchand boasts that the movement was the forerunner in granting women priests privileges equal to those enjoyed by men. “Currently there are almost 30 female priests in the country,” she reports.

The APS propagates the teachings of the Vedas, and its Vedic temples are popular. But the APS also engages significantly in social service. Founded in 1921, the Aryan Benevolent Home, essentially an ashram for the homeless on the outskirts of Chatsworth, has become a major cornerstone of the APS. The APS also provides much-needed counseling and support to victims of wife abuse, rape and impending divorce. “We have established an ashram just outside of Durban to house abused women from all religious and racial backgrounds who otherwise would have no place to turn to,” says Nanackchand.

Also immersed in community upliftment is the 56-year-old Ramakrishna Center. S.P. Singh, a retired school principal who has been with the Center for three decades, relates, “The Center was founded in 1942 by Swami Nischalananda, who passed away in 1965 and was succeeded by his only monastic disciple, Swami Shivapadananda. He headed the Center until his death in 1994. Currently, the Center is headed by Swami Saradananda.”

Since Singh’s induction into the Center, seven ashrams, including one for nuns, have been constructed throughout the country. Singh has also seen a feeding scheme expand massively since its launching in the 1950s. “We feed about 7,500 underprivileged Indian and African schoolchildren on a daily basis. Approximately 1,200 destitute welfare families receive grocery hampers from the Center,” details Singh.

Regular youth camps are held to minister to the needs of the Center’s young devotees, while bi-annual yoga intensives draw attendances of up to 250 per camp. “The Center’s work is definitely contributing to the process of nation-building and is also exposing Hinduism to all sectors of South African society,” Singh testifies.

Ever since its humble origins in the shanty town settlement of Magazine Barracks in 1937, the Saiva Siddhanta Sangam (SSS) has made tremendous strides and continues to profoundly impact the lives of hundreds of Hindu families. The founding head of the SSS was Brahma Sri Siva Soobramonia Guru Swamigal. “Following his demise in 1953, he was succeeded by my father, Sri Karunaianandha Swamigal,” says deputy spiritual head Guru Ravananthar. “In all, we have launched 23 branches nationally,” he reports. His son, Ravi Pillay, 35, explains that the initial growth of the SSS was due to the initiative of the founding master and his disciples. “They used to go to the Durban city center at night and preach and sing divine hymns under the lampposts. Soobramonia Guru also meditated nights in a cemetery in the city.”

The Sangam concentrates on conducting venacular classes, some tutored by Guru Ravanathar. Sunday prayer services spread the Sangam’s messages of vegetarianism and service to mankind, but the height of its social service is a feeding program that provides meals to indigent pupils in fifty schools in Chatsworth and surrounding areas. Although its founding master declared the Sangam a universal mission available to all of humanity, it has not yet made inroads into non-Indian communities.

Temple tour: The oldest temples in South Africa are located in and around Durban. Prominent are the Siva Soobramaniar Alayam, the Vishnu Temple of Newlands and the Sathie Sanmarga Sungam, Asherville. Even the tourism-based Durban Experience website promotes visits to Hindu temples. The site states, “The Umgeni Road Temple Complex provides for all forms of traditional Hinduism. It is one of the oldest and largest in South Africa, dating back to 1883. Its architecture and central shrine are reminiscent of shrines found throughout South India. The Durban Hindu Temple in Somtseu Road was built in 1901 and recalls the elegance of the North Indian architecture, although there are Victorian and Islamic influences. The eight temples of Cato Manor in Bellair Road survived a rocky history when apartheid laws evicted the Indian community from the area. Today regular religious activities include an annual fire-walking ceremony.”

“Encouraging for me is the high turn-out of the youth to temples on auspicious days,” punctuates twenty-year-old Niren Maharaj, a student at the University of Durban-Westville. Undaunted about the future, he says, “There is no doubt that Hinduism is destined to prosper and grow. It offers great hope for the future.” Revealing a little missionary spirit of his own, he challenges, “I would like to urge all Hindus to become vegetarians and to practice yoga and meditation. Only then will we experience the magic of inner peace and serenity that Hinduism can bring.”

SATYAGRAHA

FOUNT OF CHANGE

THE CRUSADE THAT TRANSFORMED TWO NATIONS

By Ajith Bridgraj, Durban

Eighty-five years have elapsed since Mohandas K. Gandhi sailed out of South Africa to change the course of India. But South Africa was transformed, too. “Gandhi’s twenty-year stay here, from 1893 to 1913 was a turning point in the history of South Africa,” ventures Ravi Govender, curator of the Durban Cultural and Documentation Centre. He notes that “President Nelson Mandela often quotes the Gandhian ideals of satyagraha (passive resistance) and ahimsa, noninjury.”

Gandhi’s presence dwells in the hearts of South Africans and lingers through several memorials. The Phoenix settlement–erected during Gandhi’s stay–still stands, albeit in a dilapidated condition. Talk abounds about renovating and preserving it for historic and tourism considerations. In Pietermaritzburg, a plaque marks the spot where he was ejected from a train, the crucial event that catalyzed his political struggles. An impressive statue of him adorns Gandhi Memorial Hall in the KwaZulu-Natal town of Ladysmith. 1Ú21Ú4