BY VATSALA SPERLING

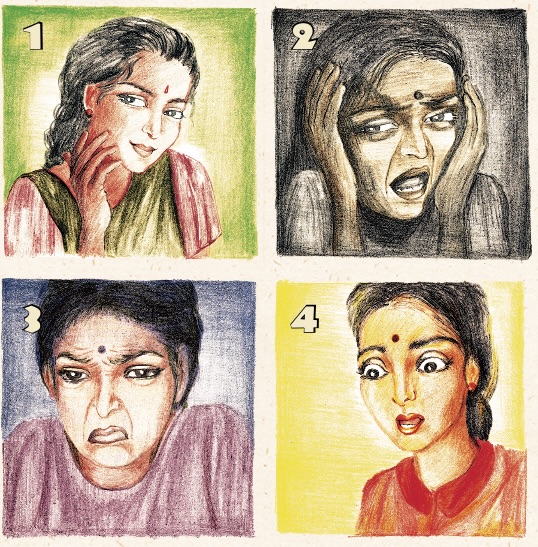

Indian tradition recognizes nine rasas as representing our most important and basic emotions: love, joy, wonder, courage, calmness, anger, sadness, fear and disgust. These emotions are universal to mankind. Five are desirable, while four are unpleasant and usually undesirable. Poets and artists have used the rasa system to express these inherent emotions in works of art. The poet-saint Thyagaraja has composed numerous classical Carnatic songs with one or another of the rasas providing the song’s theme. Artists who learn classical Indian dances, like bharata natyam, kuchhipudi and so forth, spend decades under the expert eye of a guru, mastering the mudras (facial expressions, eye-movements, hand gestures and body language) that depict the various rasas. While adults must study for years to learn an accurate expression of the rasas, a child knows instinctively how to express the rasas in a natural, perfect and pure way.

Watch a small child carefully and you will be able to see displays of all nine of the basic emotions: 1) A baby smiles and gazes adoringly at his mother, showing the emotion of shringaar, charm or love. Overcome with love for the infant, she picks him up, cuddles him and showers him with kisses. This is what the baby wanted, a physical confirmation of mother’s presence and love. He knows exactly how to display his needs by way of facial expressions when he is barely three months old. 2) A loud noise startles and wakens the baby and he cries out in fear, bhayanak. This cry is distinct from all other cries. 3) Try spooning a cooked and mashed vegetable into an infant’s mouth. As he sniffs, tastes, spits out and makes a horrible face he is expressing bibhatsa, disgust, with the new taste, very different from that of milk, his staple diet so far. 4) A ladybug lands on his table, walks across, flutters her wings and takes off. The child is wide-eyed with adbhut, wonder or fascination, and has watched every move made by the ladybug. 5) A child has learned to climb a ladder and gets a better view. He is feeling very accomplished and veer, brave, a hero of his own world. 6) Laughing when tickled is a child’s expression of haasya, joyous humor and laughter. Watch him play with a pet. 7) In a hurry, the mother stubs her toe and cries out in pain. A child as young as two, will reach out, wipe mom’s tears and touch the injury in an expression of karuna, compassion, empathy or mercy. 8) Children fighting may display roudra, anger. 9) A well-fed and relaxed baby that is asleep does look angelic. He is shanta, tranquility or calmness, personified.

Besides these, a child can display with equal ease and mastery a few more inherent emotions, such as greed, selflessness, obstinacy, curiosity, clinginess, generosity, dependency, violence, arrogance and rudeness.

Understanding these childhood emotions

In our alarmingly individualistic modern societies, the transmission of a collective child-rearing wisdom is either totally lost or seriously damaged. The barrage of advertising and information that bombards us through the media persuades many young parents to accept propaganda wholesale instead of following the intuitive wisdom of their own hearts. For example, consider this piece of propaganda from the baby formula manufacturers, “Breast milk is polluted with pesticides, give the baby formula.” This ad slogan has stripped millions of children of their birthright–mother’s milk. “Let the child cry himself to sleep. If you run to the child every time he whimpers, he will learn to control you, will never sleep through the night and will never be independent.” This propaganda has successfully deprived millions of children of their mother’s soothing touch and presence. It has taught them to ignore their natural needs for love, warmth and responsiveness. Children whose parents follow this advice grow up deprived of the trust that their cries for help will be heard by those who care for them. They do learn to cry themselves to sleep, no doubt, but who can deny with any authority that they also learn (in their nursery full of stuffed animals) that it is okay to ignore others who call for help and kindness. Perhaps these children find themselves incapable of extending any deep, lasting or genuine emotional warmth when they grow up. “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” This saying has caused many children to be beaten black and blue. All of these misguided approaches to child rearing befall children in modern societies when all that they are doing is being children–expressing, without censorship, the rasas that are inherent in them. Any society that expects children to have the self-control of adults has no tolerance for, or understanding of, the natural state of children.

When a child is raised on the basis of propaganda, rather than on the principals of a child-centered cultural wisdom gathered over the ages, he or she learns from a very early age to suppress, divert, subjugate, hide, be ashamed of and feel guilty about the expression of fundamental emotional states. While parents continue to believe that they are doing the best for their children, they never stop to wonder about the long-term outcome of the emotional suppression they have been encouraged to visit upon kids at such an early, impressionable age.

In fact, such early stomping out of a child’s emotions is damaging. When a society thwarts its children’s natural expression of inherent emotions, without first providing a healthy venue for the complete expression and blossoming of their growing minds, it creates problems for itself. The fact that these problems are specific to modern societies cannot be disputed.

How older cultures respond

The older, child-centered cultures take a different approach to the display of rasas by the powerful beings called children. The parenting techniques followed in many so-called primitive cultures foster attachment, and create such a closeness and bond between mother and child that the mother develops a total acceptance and understanding of her child and his mind. When an entire extended family lives in a one-room longhouse in the rain forest of South America, the adults reach a high level of tolerance to childhood display of rasas. They do not expect the child to conform to the expectations of the adults the moment he opens his eyes to this world. Discipline and assimilation into the community will come later, by way of the numerous rites of passage.

In a similar fashion, the child-centered and ancient culture of India takes a very tolerant view of the childhood display of rasas. In India they let the children be children. They understand that childhood does not last forever. Soon enough the child will grow up and learn the ways of the world. There is no need to rush the process, to cause premature aging and untimely maturation.

When children have strong emotions, the adults do not feel the need to resort to violent beatings or verbal abuse to suppress the expression those feelings. Such a response would only inflict rejection and social humiliation on children for their natural displays. Adults in these older cultures understand that just as a lion hunts a deer, the child, in all his innocence, is simply following his inborn instincts. He is not acting to please or displease. These adults understand that just as nature expresses herself through her elements, children express themselves through their displays of rasas. The display is not the child. It is just a state of mind and therefore is inherently changeable.

Though the expression of rasas is a life-long process, it does not go on and on in the same hyperkinetic fashion as is seen in childhood. If a child is allowed to be a child and at an appropriate time is exposed to other possible ways of channeling and expressing the rasas, his emotional health does not suffer from suppression. He can be emotionally expressive and free and at the same time learn how to bring his rasas to the surface in a socially acceptable way.

A practical approach

I was raised in India in a modest home with five siblings, each more expert than the other in his or her ability to drive Mother up the wall. How did my mother deal with it? As I recall, the weapons in her arsenal were love . . . love . . . love, endless patience, endless tolerance and a lasting belief that “this too shall pass.”

I also recall Swamiji Chinmayananda talking to a group of young mothers after a Sunday Balavihar. He said, “For the first seven years, treat the child as if he is God; for the next seven years treat him as you would treat a servant; for the next seven years treat him as if he were a slave; and for the next seven years and beyond, treat him as if he were your friend.”

He went on to explain why. “A child in his first seven years is in the realm of innocence. He lives in the here and now. He is ruled by his inborn instincts and impulses and is mainly governed by his bio-physiology. He has no awareness of the duality of the adult world. He has no malice. His love is pure. His hatred and anger are pure; so, too, are his fears, compassion and violence. In his purity and innocence he is God-like, akin to the elements of nature. At this stage, there is no need for bringing about changes in a child’s expressions of emotions by inducing fear, beating, berating, humiliating or forcing the child. Let him weather the storm. Let him live through his emotional upheaval and outburst.

“In the next seven years, the child’s milk teeth are falling. He has been through a few childhood illnesses and is aware of pain. He is beginning to read and write. Now the child, just like a servant, is ready to obey authority. He is eager to learn what will please his parents, teachers and friends. He is beginning to figure out what brings him praise and goodwill. Treat this child with the utmost dignity. Into his receptive ears, pour all the good moral stories from cultures around the world. Don’t just read like a machine. Read and discuss the stories with your child. Encourage the child to think, imagine and question. Set a positive example and be a good role model for your child to emulate. Appeal to the child’s inherent sense of justice, fairness, love, compassion, kindness and reciprocity. No child has ever been born without these beautiful qualities, ” said Swamiji, his bright and lively eyes blazing with conviction.

“For the next seven years, treat him like a slave, in the sense that he should now learn that life has serious responsibilities and obligations. To do this you do not have to become a cruel slave driver. Teach him about money, social codes and ethics, about the value of work and education. Teach him to respect physical labor. Encourage him to accomplish challenging tasks that will give him strength and confidence in himself. Teach him about consequences, the ripple effect and repercussions. And once your child has reached twenty-one years of age, stop treating him like a child. If you have treated him right from the first day, he will know to take charge and be a man. From now on he will be your friend for rest of your life, and you will be his friend.”

It need not be told that life begets life, tolerance breeds tolerance, love generates love, hatred brings more hatred, violence leads to more violence. The natural display of rasas during childhood gives parents and children an opportunity to make a fresh and correct start. A child raised in an environment imbued with love, acceptance and tolerance learns to accept these values as natural and can find in himself a reserve of these very same qualities, from which he can give to others freely when needed. A child raised on anger, hatred and violent discipline learns that his basic, inborn, inherent signals, the instincts that lead him to display the full range of rasas, are all wrong. This negative feedback toward his most natural, instinctive behavior causes him, in turn, to lose trust in himself and in others. The final outcome is a suspicious, doubtful, cold, emotionally dead and ruined adult who has chronically low self-esteem.

WHAT PARENTS CAN DO

When the display of negative rasas by children gets out of hand, there are certain positive things that parents can do:

Take a few deep breaths.

Commit to loving the child without conditions.

Be firm, yet remain flexible to the child’s needs of the moment.

See the child for what he is–just a small child in need of support.

Impose no grown-up values and expectations on the child.

See the display of rasa for what it is a little storm in a tiny tea cup, which will calm down eventually.

At the peak of the display of negative rasas, do not force the child to change his ways or engage with him in a forceful manner. A calm voice and a firm but peaceful demeanor is a stronger weapon than force.

Do not, do not, do not suppress, neglect, ignore, put down, discourage, demean or humiliate the child when he is displaying any sign of a positive rasa. While excessive praise is detrimental, so are neglect and discouragement.

At no point are violent physical punishments, frightening time-outs, deprivation or verbal abuse called for. These negative devices affect children for the rest of their lives.

Focus on cultivating tolerance and patience in yourself. Treat the child as you would expect him to treat you when you grow old, powerless, dependent and needy. Talk to your child about the expression of positive rasas when the time is right. In the meantime, just show him by the example of your own behavior how the expression of positive rasas brings joy to the family.

Set a family time–free from technology–to create an ideal environment for cultivating your child and teaching him about the display of positive rasas.

Soon enough you will be able to speak to the child about the universal laws of righteous behavior. Every being has the desire to be treated with love, courtesy, kindness, loyalty, generosity, consideration and warmth. While being taught to extend this treatment to one and all, the child will also need to be told about discretion. For example, loyalty is a good quality but the child must learn to choose his company wisely. If he befriends a drug pusher and becomes loyal to him, his loyalty to this friendship will quickly take him right down the drain and into the septic tank. This is where discretion comes in.

When all is said and done, nobody can deny that these are challenging times for parents. Rootlessness, alienation, marginalization and anonymity–these are some of the prices parents pay when they move around the world in search of the perfect situation. Young parents are often cut off from their original cultures and societies. Techno-commercial values constantly push parents and children to test one another. In pursuit of their individual ambitions and needs, parents and children often live in separate worlds, albeit in the same household. And when children enter school, the child who has not been given time to be a child, who has not been accepted with tolerance, often ends up in the school nurse’s office being tested for and diagnosed with illnesses such as bipolar disorder, ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder.

Harried teachers, under pressure to maintain order in their classrooms and to have their students meet minimum academic standards, expect all of the children to behave like obedient, quiet, perfect, little ladies and gentlemen. Children are not allowed to be children. They are not allowed to deviate from the norm or to freely express all of their rasas. Sometimes as early as the age of three or four, children are labeled with psychiatric diagnoses and begin to be treated with powerful drugs such as lithium or Depakote (mood stabilizers), Risperdal, Seroquel or Zyprexa (atypical antipsychotics), Prozac (an antidepressant) or Ritalin (a drug for ADHD). Each of these drugs comes with a frightening list of side effects. If prescribed without any physical markers, but solely on the basis of behavior–or rather the display of rasas–what good (or harm) is being done to the child, the parents and society?

In the face of this, it becomes all the more imperative that parents consider other, more holistic approaches to child rearing. If, as is sometimes the case, the child’s display of rasas becomes detrimental to his own or his family’s well-being, there are scores of other, non-pharmaceutical options available for modifying mood and behavior. His parents might explore changing his diet, limiting his intake of sugar, preservatives and additives. Calming and healing herbs might help. Perhaps homeopathy could shift his energetic balance or counseling for the entire family could diffuse the situation. Training a child in martial arts, classical music or classical dance could help. All of these disciplines have been known to stabilize and channel excessive or disruptive energy in more positive directions. A regular TV-free time when family members sit together, work together and converse with one another is also known to provide lasting positive change for children.

As children grow up and display rasas, parents need to continue to grow up as well–not just in the physical manifestations of age, the wrinkles and gray hair, but in wisdom. This is what a study of the display of rasas in childhood is all about: a call for parents to monitor the growth of their wisdom. When parents learn to take charge of their own growth in terms of tolerance and empathy and resolve to let children be children first, allowing them an age-appropriate display of rasas, they have an opportunity to become truly close to their children and know them in their totality. As children mature, good parents take the initiative for gently channeling their rasas at the appropriate time and place. When parents take this positive approach to child-rearing, the options of violent discipline and drug-based treatments become obsolete. While we continue to ponder who is raising whom, learning to flow with the rasas will bring about lasting peace and joy in many households.

Author Vatsala Sperling may be

reached at vs@innertraditions.com