To assess the religious ideas and opinions of youth of her generation, our author posted a questionnaire and followed up with phone calls

BY PALAK MALIK, NEW DELHI

WHEN HINDUISM TODAY ASKED me to interview a sampling of Indian youth about their religious views and practices, my first reaction was to somehow escape the situation entirely. India’s political environment is so intertwined with religion that to engage with others on the topic is to risk being stereotyped. HINDUISM TODAY suggested that we focus on the personal religious lives of individuals and not the Indian politics of religion. I wondered how to make that distinction. Where I come from, the lines are very blurry.

I struggled to wrap my head around this idea of my talking to youth about their ideas and understandings of Hinduism. Did I even want to do this? Secretly, yes, because I struggle with my own ideas of religion on a daily basis, and I’d like to know what my peers think. Rarely do you get a chance to delve deeper into the beliefs of others.

And how does one tap the pulse of youth? Who should I start with? How could I find the right sample to represent the views of the whole of India’s young adults? Frankly, a full and accurate representation is simply not possible and is not what I was able to assemble. With the help of my father, Rajiv Malik, I developed a questionnaire that I hoped would inspire respondents to reflect on their life and personal evolution with respect to matters of faith. The next challenge was to identify our survey range. My father suggested we seek respondents from diverse fields, jatis, communities and different Indian states. For practicality and my personal comfort, I favored a smaller scope, so we agreed to limit the survey to metropolitan youth. Still, the hope was to encompass the entire spectrum, from utter non-belief to unquestioning devotion.

After much discussion, we settled on a set of questions for our online questionnaire. The first segment focused on personal religious beliefs, with emphasis on the environment where one grew up. We designed this set of questions around temple visits, festival celebrations, family pilgrimages and daily rituals. We wanted to evoke memories of childhood in relation to religious practices, and hopefully evoke thoughtful answers.

This led to one of the most pertinent questions one may ask: “Do you today self-identify as a Hindu?” Based on this one answer, we crafted two paths. If they identified themselves as Hindus, we delved into their ideas of God and other religious practices and beliefs, including karma, dharma and reincarnation. In terms of practice, we asked, “How does Hinduism manifest in your life?” We also inquired about the differences they perceive between themselves and the older generations in their household.

For those who no longer identified themselves as Hindus, we followed with different questions. Were they atheists, agnostics, a member of another religion, spiritual but not religious? Were they more in the millennial “I just don’t care” category? At what point did they become estranged from Hinduism. What issues, philosophical or otherwise, did they find troubling? How do they interface with the celebration of Hindu festivals and other events which are so prevalent in Indian culture? Finally, what they would want to change about Hinduism.

We approached only those who were born and raised in India. We gathered 36 individual responses. For the eleven that were most articulate and open to further questions, I followed up with in-depth interviews by phone. Eight of those are featured here. Most of our respondents were urbanites in their twenties. Obviously, the views expressed here do not reflect all—or even most—of India’s Hindu youth. We would especially expect different answers from youth in the vast rural areas. All responses have been edited for clarity.

Aastha Taneja, 28

Before we approached our interviewees, we did a pilot run of the questionnaire with my first cousin Aastha Taneja, who lives in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh. When asked about the effects of religion in her life while young she mentioned, “In growing up I never really noticed people discussing religion or noticed religion having an obvious impact in their daily activities. I was brought up in a quite liberal household with no stringent rules about following our faith. My parents are reverential toward God and do believe in a greater power; however, they have never performed any overtly religious activities.”

Aastha’s mother is more religious than other members of the family. She is vegetarian; the others are not. Aastha developed a liking for meat and has continued to eat it. “I believe no one should impose rules about what an individual can eat or not. Religion can’t dictate what foods you like.”

As do most Hindu households in India, Aastha’s house has a shrine room with figurines of Hindu Gods. “My parents pray daily, but I don’t participate. We are free to choose if we want to or not.” When our interview touched on the ritualistic practices of Hinduism, there was a slight resistance. She considers rituals dull and boring. This was typical of many youth I interviewed: their fast-moving lives take center stage, and religious practices, often misunderstood, seem onerous and unnecessary. Aastha believes in the presence of God, but does not feel a need for daily prayer. “I do recite the Gayatri Mantra when I feel like it, and going to the temple makes me feel good—empowered and happy.” Still, she attends temple much less frequently than when she was younger. While growing up, she and her parents would pilgrimage to far-off holy shrines in other states, and these memories now evoke a feeling of nostalgia and family time.

Like most of India’s Hindu families, Aastha’s family celebrates major festivals, including Holi, Diwali, Dussehra, Makar Sankranti and Lohri. Her favorite festival is Diwali, because it means get-togethers with extended family for serious festivities. “It’s one of the most celebrated and biggest Hindu festivals, and people seem happier during this time of the year.”

By talking with Aastha, I became aware of the growing divide between private and family life that many youth experience. Aastha, does not follow rituals personally, as they seem inconvenient or unimportant, but she participates with the family in collective activities like festivals and pilgrimages.

By now I was beginning to realize the complexity of the subject I was dealing with. Through the questionnaire and the follow-up interviews, many paradoxical statements would come to light. This can be partly attributed to the two phases of life that we are accounting for. Initially, parents play a very influential part in defining a child’s habits and behavior. For instance, Aastha’s mother used to make her recite alongside her as she did her own puja. “But when you start growing up, it depends on you if you want to take it forward or not. My parents have never forced me to pray, but they have always taught me how and encouraged me and my brother to be thankful for what we have.”

She also grew up on heavy dose of mythological stories; watching TV episodes of the Mahabharata or Ramayana on Sundays was practically a family ritual. For those like Aastha and myself who grew up in the 1990s, there was no cable TV, and these programs were consistently played on the one and only Indian National television. “We were watching it all for pure entertainment. Only later have I personally understood the meaning of the Gita, or of the politics and teachings involved in the Mahabharata. I personally find Mahabharata one of the most interesting works I have ever read.”

Aastha seemed unsure how to describe the depth of her religiosity. “I have belief in God, and we have so many of them”—but she said she isn’t doing anything on a daily basis. How does Hinduism manifest in her life? One aspect Aastha mentioned was the red thread, the mauli, that is an obvious symbol of the faith. “That’s a clear giveaway of my belief in Hinduism. I consider it sacred and wear it most of the time.”

In this conversation and those that followed, I was particularly intrigued that while other religions may make the distinction between practicing and non-practicing members, in many Hindu traditions, participation is completely up to the individual.

“Today’s youth want freedom. They want to do things in their own way. If you try to force anything on our generation, they will not accept it.”

Saagar Sharma, 26

Saagar was born and brought up in a religious environment and currently lives in New Delhi. His parents perform daily rituals that include arati and the chanting of the Hanuman Chalisa. Saagar joins his family for sahaj yoga on a weekly basis. “It is a type of meditation. Every Thursday our whole family goes to the center. It is definitely a religious activity for us.”

Saagar firmly believes in God and prays often. “I do not go to the temple each morning or pray to God every morning, but I do have faith in God. When I pass by a temple, I definitely bow my head in reverence. At the same time, I am not a very consistent Hindu. I am not an extremist. I am very practical. In fact, Hinduism allows one to be practical.” In his view, the Hindu religion has become more flexible. “There is a great difference between how my parents approach things and how we approach things.”

Saagar and his family celebrate every major festival. Diwali is his favorite, “because it’s the festival of lights. Every corner, every home is decorated and well lit. It brings a lot of positivity.” He has also pilgrimaged to holy sites like Haridwar, Amarkantak and the Vaishno Devi Shrine over the years.

“Youth connect to religion in their own way. Those I’ve come across at the sahaj yoga center take their religion very seriously. Youth and even some young children are curious about learning meditation. Many are deeply involved in meditation. A lot of youth my age come to this same center, and it is clear they are committed to their faith, even though many of them do not talk about it or show it off at all. Personally, I mix with this kind of youth, but I also have friends outside this spiritual circle. So I have to maintain a kind of balance between relations with both sets of people. For many, their religious path is very private and is not discussed with others who are not a part of their spiritual group. I only share my interest in spirituality, and related experiences, with those who take keen interest in my spiritual life.”

Saagar observed, “I feel Hinduism is the most liberal and complete religion. Today’s youth want freedom. They want to do things in their own way. If you try to force anything on our generation, they will not accept it, whatever their religion may be. The society is getting more and more liberal, and the level of education is also becoming higher.

“On a scale of one to ten, I would rate my religiousness as an eight. I am not one to judge as right or wrong the various practices within our religion. For instance, some people will blindly follow the teachings of the Ramayana or Mahabharata. I do not. I take out the positive teachings that apply to me and leave the rest. The Bhagavad Gita, too, has a lot of nuggets of wisdom; for instance its discussion of karma and also the idea of being a free soul—coming here without any attachment and then leaving this world without any attachment. Going through the scriptures and their teachings does help in your practical life. While performing your day-to-day chores, you have a foundation for what is right or wrong.

“Your thoughts about divinity are also related to the kind of people you meet regularly. They, too, influence your thoughts. I do feel that there is divinity in the people around me, such as in my family and friends.”

Shreya Dubey, 21

Shreya is a college student currently living in New Delhi. She grew up in a Tamil brahmin family that housed three generations under one roof. She describes her grandfather as highly religious. She remembers his daily morning and evening pujas ever since she was a child. Her parents are only moderately religious, they follow the same routine. “While growing up, I was required to visit the temple. Even if I had to attend my coaching classes, I had to find the time to go. For my parents it was important, despite my struggling to manage and being somewhat unwilling.”

Shreya feels her family’s approach to religion was too restrictive. The brahminical expectation to follow rituals and religious activities seemed heavy. “For a long time I would do the morning and evening puja. But when I was 15 or 16 years of age, I could not understand why my family were doing these rituals.”

In many situations Shreya continued to follow what was asked of her, mainly to avoid upsetting her parents. “My parents chant ‘Radhe Radhe,’ and I did not. But this was causing conflict. So I decided that if my saying it makes them happy without comprising who I am, then I might as well do it.”

“A lot of youth are moving away from their families for education or work, and they are seeing more of the world. That is possibly one of the reasons for this difference in thinking. While this reflects my situation, at the same time, I have cousins from orthodox families who keep adding me to brahmin WhatsApp groups and the like. So for me it’s like dealing with two different worlds.”

While not opposed to Hinduism, Shreya respects people’s right to hold their own views and opinions. Her family is strictly vegetarian, and her mother can’t even bear to see meat on a TV screen. In her home, it is not even a point of discussion. Shreya felt she had to make her own decision. “I tried everything [meat]. I did not like any of it. I opted for vegetarianism out of a choice, mainly because I am against killing animals.”

Asked if there was anything she would like to change about Hinduism, she said she would like to make it a bit more flexible. “I see it as more like a way of living rather than the highly political religion it has been made into.”

She does not appreciate it when things are taken to the extreme or when certain practices are forced on her. “Only this afternoon my mother was telling me how she wanted me to get married by 24 with a brahmin boy, and the boy has to be a certain subclass of brahmin. So, he has to be a Hindu, he has to be a brahmin. Brahmin over everything.” Her mother believes the right age to get married is 20, as mentioned in the Vedas. Shreya is already past that age, and the pressure is building.

Shreya explains she has never felt estranged from Hinduism, but Hinduism is being represented in a skewed manner. “At one point I just felt ashamed and scared of my religion. I don’t feel that way anymore, because I know that what the media and others are portraying as my religion is not really what my religion is.”

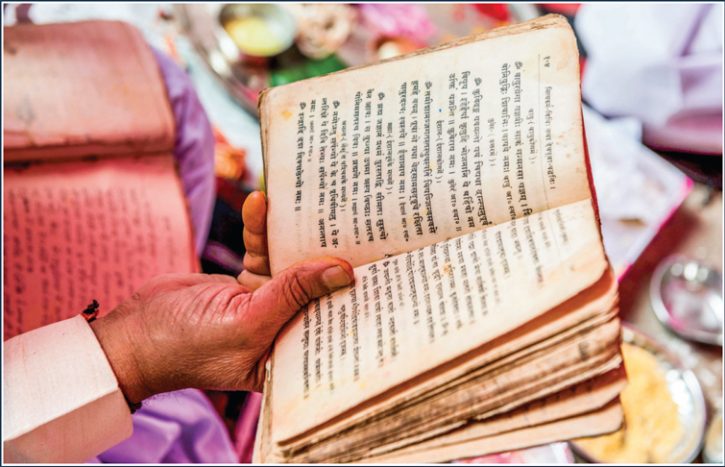

As she is deeply interested in Indian psychology and knows a bit of Sanskrit, she started reading the original Bhagavad Gita. She quickly realized that the essence of the book was being distorted in its translations. “Few people read Sanskrit, and the problem arises when they follow the distorted versions of the book. Recently I started reading a translation of the Gita that my grandfather gave me. It is so hideous! In the first few pages it says that if the women of a house are left alone then their dharma becomes impure. The original Gita never said that!”

At this point, Shreya considers herself as spiritual but not religious (SBNR), which is the fastest-growing category of belief in many nations. “I am basically making my own religion, and I’ve been trying to do that for some time.” In the process she draws inspiration from Hinduism itself.

Modern views on an ancient faith

“The Ramayana talks about integrity, which I value highly. I think not compromising integrity is something I learned from it.” Today she can debate whether Ram is an ideal to follow, but when she saw a Ramayana cartoon as a 6-year-old, she clearly understood that Ram left home because he did not want his family to break down. “I think I would do the same; but then again, if it at any point stopped me from being my own person, that’s where I’d draw the line.”

Shreya enjoys all Hindu festivals, both for the family closeness and for the delicious foods that come along with such events.

She also practices meditation, because she wants to be in a state of constant awareness. For her it’s a way of knowing herself, and she feels that she carries a sense of divinity with her through life. “I believe you should be tolerant and respect other people’s opinions, cultures, and everything else that is different from yours.”

Sonam, 22 (Anonymous)

Sonam grew up in an extremely religious, ritualistic family. From the beginning, she felt she was being forced to go to the temple and to participate in daily prayers and perform rituals that she did not identify with. Her actual disconnect with Hinduism happened over an unfortunate turn of events that affected her personally. Sonam was close to her grandmother. She happened to be in Kedarnath when her grandmother fell ill. “Unfortunately, my prayers did not help her recover. That is the time I realized that God exists in our imagination. There is no way of knowing if God exists or not.”

Over time, she has started identifying as an atheist. “As I grew up, I realized that religion is just a way to anchor one’s life, to give it morality and meaning, even though there is no tangible evidence that an omniscient, omnipotent God exists.” Her atheistic beliefs became more entrenched after she attended the Jesus and Mary College Christian college. “It made me realize that all religions are the same in structure; just the rituals/gods/artifacts/history are different.”

“I see a lot of discourse now which wasn’t there before. I see a lot of young people even trying to defend the old practices if they have any merit to them”

Sonam believes all religions including Hinduism exist on the principle of instilling a feeling of “fear of God” in people. “Religions say, ‘Do right because God is watching you and you will pay for your deeds.’ It forces a morality on people which people follow due to fear of punishment.”

She believes that it is generally difficult for most people to have an internal moral compass. That motivates them to look outside of themselves, to believe in God. With God as their motivation, they are able to exhibit good behavior, as they fear the consequences, such as facing hell. “Personally, I believe it is good to be kind to people. I think I am a better person for not doing good things out of compulsion. Also, if I am kind to people, they would naturally also be kind to me. For me it forms a reciprocal relation with people.”

Despite being an atheist, Sonam participates in Hindu festivals for the sake of her family’s happiness. She recalls how Holi was her favorite festival while growing up, “Because it was only a small ceremony and I could play with water and colors with my friends afterwards.”

Most of the youth Sonam interacts with come from devout Hindu families and rarely question their elders about the religion. “They do not deal with religion and religious beliefs in a critical manner.”

It is her observation that her generation are less ritualistic in their religious practice. “I do not think that people of my generation hold such lengthy pujas as my parents do, nor are they performing idol worship in such a devout manner.” She attributes this to modernization and the growing influence of Western culture. India’s religious landscape has changed owing to the global sharing of information through technology. “Earlier we were unfamiliar with other cultures, and we did not have the knowledge of what was going on apart from our own religious viewpoint. We are now at the cusp of an information revolution and possibly due to it we become more irreverent (if I may say so) towards following lengthy rituals, pujas and havans.”

Sonam believes that with the BJP in power, religious politics has multiplied manifold, and religion is increasingly used as a tool to control people. “Recently, during Eid there were objections raised to the slaughtering of animals. But Hindus, too, slaughter animals, for example last year when I visited Kamakhya Temple in Gauwhati I came across slaughtering of animals.” Moreover, Sonam believes religion creates hostility towards other religions. “I feel that religions make you blind to reason. This happens whe one is opposed to other religions.”

Vignesh Karthik, 25

Vignesh also lives in New Delhi. He grew up in a religious family that prays to Lord Siva. He says that while young, he was taught hatha yoga and meditation, “but my fondness for mixed martial arts does not give me time for hatha yoga. I meditate regularly and I have been taught a practice called shambavi mahamudra (shakti kriya), which I do as a spiritual exercise.”

In his youth, most family outings comprised visits to temple and other holy places. To this day, he goes to a temple twice a week. “It started as something my mother wanted me to do, owing to an astrologer’s insistence. Now it is more to help me focus and feel better.”

Vignesh has become an avid seeker. “This enables me to better myself with every passing moment. Furthermore, God has helped me fathom the essence and potential of ‘I do not know.’” He believes that the experience of religion or spirituality can be better if the potential of “I don’t know” is explored.

His search is a constant process of learning and unlearning. “Belief systems are great, but I’d want them to be a small core of my being.” He holds himself open to all sorts of new ideas and thoughts, whether they come in the form of criticism or differences.

Vignesh credits the core values of Hinduism for his decision making. He says Hinduism has been an important source of information in his life. It helps him form his arguments and opinions, on both abstract and pragmatic dimensions. “I used to watch The Ramayana (the animated version). However, I really loved reading Ramayana and Mahabharata. Considering the fact that I know the stories quite well, I go back to them with a different view every time I get an idea or a chance. For example, ‘no violence against women, no matter what’ is something the Mahabharata has taught me so much.”

Even when making small, simple decisions, like whom or where to help, Vignesh looks at the intent of the person and not just the action in isolation. “So, looking at how I make decisions, I have a value system. It came from my mom, and she got it from the God that she worshiped and the stories she had heard, stories she has told me. I’m always trying to forgive a person who didn’t intend to cause harm.”

Vignesh is a student of identity politics. He feels youth are not trying to ape Western culture. “Just because I walk into temple wearing jeans and a t-shirt doesn’t mean I am any less Hindu than you are. It is convenient, instead of draping an entire dhoti, which is uncomfortable for me.”

Youth, he says, are not trying to denounce the religion, but rather to adjust it. “I would want to make it more inclusive, egalitarian and less rigid. We just need a few good people, because I believe revolutions are started by just a handful. The ideations and the discourse just happen amongst a few people. It’s the dissemination that has to happen in a large scale.

“I see a lot of discourse now which wasn’t there before. I see a lot of young people even trying to defend the old practices if they have any merit to them.” He firmly believes we need to preserve the spirit of questioning. “Even a cursory look, even a bird’s-eye view at our history tells us that only discussions, debate and non-violent engagement have brought us results, and not violence in any form.”

Vignesh thinks of karmas as the building blocks of one’s life. “If you sow good things, you get back good things. I came across an interview of A.R. Rahman (Oscar-winning Indian music composer), where he said if you do a wrong thing, don’t give up—don’t go around feeling guilty, but instead compensate with ten good things. I think that’s a great practice.”

“I have a set of principles that guide me involuntarily. For example, I don’t resort to violence, I don’t resort to lying to people, I don’t resort to cheating. This just happens naturally.” In his view, Hinduism manifests as a tool to navigate the journey of life. “Religion is a tool just like the GPS. Spirituality is the destination.”

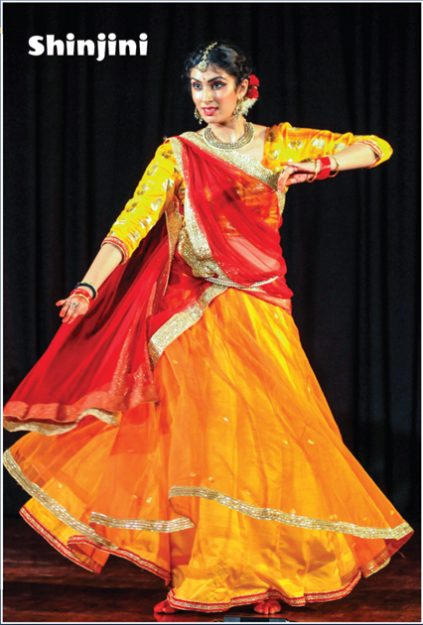

Shinjini Kulkarni, 24

Shinjini lives in Noida, Uttar Pradesh. She is the ninth generation of Kathak dancers in her lineage, and is the granddaughter of Kathak maestro Pandit Birju Maharaj. Kathak in its essence means story, and from a very early age she was exposed to the art of performance storytelling. “From the very beginning, when we were growing up, he taught us shlokas and vandanas which we perform in dancing. Otherwise, a young child of three or four years will not remember Sanskrit shlokas, right? So, when you are dancing to it, to a tune, then automatically you know it by heart.”

She grew up in a religious atmosphere. “My family taught me how to practice religion. We are devotees of Shri Sai Nath of Shirdi. In our family, we believe Sainath is like the elder of the house, so he is going to take care of everything. If you have a worry, give it to him. If you have a desire, give it to him. It can be the most worldly desire.”

“We all want to seek and connect to something which is divine, more powerful and bigger than ourselves.”

Other than daily puja, their emphasis on ritualistic practices is minimal. “Daily prayers are offered, but the time of puja isn’t fixed. Also, it is not any one person’s responsibility to offer the prayers. At the same time, lighting of the lamp is a must.”

Her family celebrates all major festivals in a traditional way. In addition, katha (religious storytelling) is held approximately every three months. “For Janmashtami, an annual Hindu festival that celebrates the birth of Krishna, puja happens at 12 midnight, and we do the whole Krishna Janam Leela. Krishna is a very important God for dancers, so we celebrate it with a lot more fervor.

“We also celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi and smaller festivals like Beej and Pradosh.”

Festival celebrations in Shinjini’s house focus more on bhava, or emotion, rather than ritual. For example, she recounts when the family brings Ganapati to the house for Ganesh Chathurti, according to ritual you have to keep a modaka, an Indian sweet, in his hand, and offer him sweets because he is a revered God. “Instead I imagine you got this really cute young boy whose parents have dropped him at your house. He is a guest for five days, so you try to keep him happy and indulge him with love and affection. That sort of bhava becomes more important than the ritual.”

Tradition through dance

Hinduism forms an important part of her personality and identity. “Hinduism gives me roots, and allows me to use the knowledge of great seers and sages to nurture my own soul. But if I wasn’t a dancer, I probably never would have taken so much interest in mythological stories or the ritualistic traditions.”

Shanjini practices meditation as a part of dance. “It is a unique exercise among the kathak dancers. We gradually raise the tempo of our footwork and concentrate on the sound of our ankle bells. The constant sound in a balanced tone is like repeatedly chanting a mantra, and helps us to focus our mind, and meditate.”

Indian classical dance is based on Hinduism. “Thus, Hinduism manifests in my professional life in the form of choreographic pieces that I perform, or teach to my students.”

In India, she feels there is a huge difference between the North and the South. “The normal children who are studying at various public or private schools in North, when they come and take dance classes with me, I have to teach them the very basics. I have to tell them who Vishnu is, who Siva is, because usually a five-year-old child from the North has not been taught this at home by their parents or grandparents.” Whereas, in the South there is a lot of emphasis on teaching children classical dance and music to inculcate cultural values.

Shinjini also teaches underprivileged children at Sai Sanstha. “These children, brought together under the Shirdi Sai Trust, have been taught about his life stories and the whole concept of praying daily. So they are very devoted children and are a little more religious than the students I teach at home. ”

When she recently taught second-generation children in the USA, she observed that classical dance is a way to reconnect with Indian culture. “I realized their parents had taken active steps to give them cultural roots and religious roots via the classical dance forms from a young age, so that they don’t lose their cultural and religious touch. It is because we learn so much about mythology through the dance form. We learn all these stories about Gods and Goddesses on moral values.”

Shinjini grew up with an idealistic view of her religion, believing that Hinduism is the most perfect faith. But when she started classes as a student of history, her perspective was shaken. “In the very first year, we studied a course on Ancient India that covered Hinduism and Brahmanism and Vedic science. When my professor critiqued the Hindu religious practices, I used to feel bad. But soon I figured that people are going to have different views about my religion. I think my college experience made me more tolerant in general, and I am proud that I can listen to criticism of my religion and objectively argue back if I think it’s wrong, or even accept humbly if it’s right.”

Shinjini finds certain portrayals of women in mythological tales problematic. For example, she feels the story of Ahalya is written from a male-centric viewpoint. “I have learned to question traditions, and the reasons why they were formed in the first place. This has made my worldview more secular, and helped me demarcate religion into my private life, away from the public sphere.”

She stresses that youth today will be more devoted towards religion if they are provided with logical reasoning. She believes firmly in the concept of karma catching up with each and every one of us. But she finds the idea of reincarnation hard to believe (perhaps because Bollywood story lines have exploited it beyond believability).

Shinjini believes that while we need to move towards a more personal and deeper spirituality, religion is what binds the community together. “Imagine if there was no Diwali, that feeling of autumn or winter setting in and the whole country crazy and berserk with the shopping—buying and exchanging gifts. These customs bind us together as a country, as a community. That’s where religion is playing a part.”

Srishti Chopra, 26

Srishti labels herself as “religiously spiritual.” She lives in New Delhi, and was born in a family that practices all pertinent religious rituals, whether related to birth, marriage or death. But when it comes to belief systems, there was always freedom to search and explore. “We never visited temples. We were always free to visit out of our own choice, of course, but we were always taught that God is omnipresent with or without the existence of temples.” She does not visit temples often but does believe that temples have great vibrations of austerity.

Srishti says her personal study and learning from Hindu scriptures guide her in life. She does not remember exactly how and when she started walking her spiritual path, but notes that yoga has been an integral part of it. “When I was facing health issues while approaching adulthood, yoga came to my rescue. I feel if I had not taken to yoga, I would have become obese and been prey to so many diseases like thyroid problems and depression.

“I took to the spiritual path under the umbrella of yoga following the teachings of Sri Sri Ravishankar, through his Art of Living program.” She thinks Hinduism is a bridge to a deeply spiritual life. Here belief in the Divine and in the divinity in the world makes her “God-loving and not God-fearing. I have experienced the divine power many times when I was facing difficulties in life.”

“We try to practice religion per the scriptures. We pray to the murtis, go to the temple and also on pilgrimage. There are so many religious places in our country which I fully admire and respect. However, unlike other religions, there are no pre-set conditions, such as a requirement to visit a certain place once a year or even once in a lifetime. I am not bound by any such conditions, though religion is important to me, and worshiping the murtis in the temple is important to me.

“We all want to seek and connect to something which is divine, more powerful and bigger than ourselves. In fact, we feel that such a source of power will help us move smoothly through the hurdles, problems and ups and downs of our lives. As part of Sanatana Dharma, and as per the teachings of our scriptures, we not only pray to the murtis, but also to nature, including fire, sun and earth. Even though the sky does not have a form, we still worship it. So we worship both form and formless. I feel that the God is not just there in the murti, but is also there in all of us, and I try to understand and imbibe this knowledge.

“There is definitely a change required in Hinduism that is being followed by us today. Earlier the Hinduism we used to follow was a bridge leading to be more God loving, finding our own selves, learning to be more kind, humane and helpful.

“We should first learn about the basic values of Sanatana Dharma that have come from our ancient wisdom and inscribe those in our lives. Unlike youth belonging to other religions, most of the youth belonging to Hinduism are not well aware of their scriptures. How many of our Hindu youth today have actually studied their basic scriptures, and how many of our youth have read the Bhagavad Gita, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana? I feel our youth need to apply the teachings of our dharma in real life. Our dharma and scriptures teach us to love and serve others and this is what we need to practice. That is the whole crux of what I want to say.”

Prakash Kumar Sahoo, 28

Prakash lives in Banki, Odisha, and comes from a religious family. “My mother is very religious, my father, moderately so. Both do puja and follow all rules and regulations set within our tradition. They do morning puja and evening puja followed by spiritual text reading.”

His family celebrates all Hindu festivals. “My favorite is Diwali, because it brings all the family members together. It gives us a reason to be together and celebrate it together as well. Diwali is not just using fire crackers and lighting diyas in my village; we also honor our ancestors through chants, which I like the most.”

He grew up watching the Krishna and Mahabharata TV series, which he feels has impacted his understanding of right and wrong. “It was all about understanding the stories and characters and trying to learn good things from them.”

“Hinduism gives me roots, and allows me to use the knowledge of great seers and sages to nurture my own soul”

His mother is the only vegetarian in his family. She is deeply religious and believes that one should not kill to eat. She does cook non-vegetarian food but never tastes it. “Even though I’m a non-vegetarian, I did not know that people ate beef. When I went to Bengaluru, I stayed in a Tibetan hostel for three or four days. They eat beef momos and beef rolls, but I never ordered them. However, someone once gave me a beef roll by mistake, and I ate the whole thing. I never felt any regret about that or anything.”

He is currently working from his home town with an NGO and interacts closely with youth in his village. A lot of his friends are from his village. These youth firmly believe that their religion is the best and they are defensive about their religious practices. “A few weeks back we had a Ganesha Puja. After the puja, all these youth danced to music from a DJ while getting drunk as they took the idol of Lord Ganesha to the river for immersion. I asked them, ‘Where is your Hinduism? You all get drunk, you dance and you take the God to the river, but where is your belief system? Do you know whether God wants this or not?’ They had no answer. But they will still defend their religion.”

Prakash mentions that in his village there is a common belief that everything happens because of God. “Like if a tree grows, it’s because of God. They always say that if wind blows, it’s because of God. So, if there is flood, it means that God is angry.” But at the same time he feels the current generation has started questioning such beliefs because of easy access of scientific knowledge. “There is science for everything. For example, if there is a flood, it’s due to heavy rain. It’s not that God is angry with you.”

He thinks his generation is starting to question why we do what we do. This is unlike his parents’ generation, who took certain beliefs for granted and passed them on to the next generation. “My parents picked up their beliefs from their parents, and they obey those ideas for their entire lives without ever questioning them.”

While working with tribals in the naxal areas, he had a first-hand experience of the consequences of religious preaching. “In the village I was working in, tribals were largely converted to Christianity by Christian missionaries, before the government could even reach these remote places. Approximately 5-6 years back, there was a communal riot between Hindus and a Christians in one of the districts. The moment you start preaching one religion is better than another, the problems begin. So I have issues with the way my religion is misrepresented. I do not have any philosophical issues with the core values of Hinduism.”

Prakash does not believe in reincarnation but does wonder about questions like what happens after death. He is also unsure about the concept of karma.

New perspectives on a long-standing religion

Conclusion

Speaking for myself, and most urban youth I’ve met, we tend to think of ourselves as liberals and secular and are fairly open in stating that we don’t practice our religion that much. But our simple study here made me scratch below the surface, where I found threads of Hinduism interwoven in our everyday lives and existence.

Without doubt, youth are struggling to reconcile private and public life in regards to religious expression. Many, it seems, are living in two conflicted realities. When we say a form of salutation to please our parents, or attend festivals and events for the sake of appearances, we are forming separate identities for our family from who we are to ourselves. At the same time we feel rooted or grounded in our childhood experiences of Hindu traditions.

There is a great inter-generational gap, wherein a rational questioning of the ritualistic aspects of faith is occurring. And there seems to be a gradual decrease in ritual practice between generations, partially because youth are not receiving satisfying answers to their questions.

“The moment you start preaching one religion is better than another, the problems begin”

But judging from those surveyed here, youth are open to spiritual experiences, regardless of religious structure. Many have taken up yoga and meditation and swear by the benefits. All share the belief in a general sense of goodness or right and wrong.

Today we are living in the age of information, and with multiple sources of knowledge about our practices, with multiple answers, many hand-me-down guidelines, all of which are being questioned. This is leading to meaningful discussions and debates, bringing new thoughts and ideas. The more responses we received from youth on our questionnaire, the more I realized that the roots of Hinduism go deeper than I imagined. While at times overt practices like puja and aarti or temple visits might feel forced upon us by our parents, all the while, the subtle nuances of these experiences—which may have gone unnoticed—have become a major part of our lives and identities.

Even if you do not believe in the ideas of a Hindu god or a religious practice, chances are that if you are born a Hindu, you will remain a Hindu in some capacity. Even if you don’t get married according to Hindu traditions, your cousins will, and, who would miss a great Indian wedding? Whether you live in India or abroad, your belonging to a Hindu household will afford you a melodramatic call from Ma asking you to come home for Diwali. Because you grew up on a high pedigree of Bollywood movies and Indian advertisements, your heart will lead you home even if your head doesn’t agree, and at the end of the day, we all have an emotional side to balance out our logical decisions and justifications. Even if you hate the family drama, you do love your family. So we will all sit in the puja because it makes our parents happy. In that sense, despite our questioning and our challenges to traditions, it really is our religion that keeps the family and society together.